Customer service top priority for locally-owned banks

April 13, 2016

Narcotics commander resigns after feds lodge a charge

April 13, 2016As state legislators grapple with a proposal to raise the age for juvenile court from 16 to 17, a local prosecutor is preparing to provide unprecedented services to keep those kids out of that same system altogether.

Statewide, the bill that would bring Louisiana in line with most states by shielding young offenders from the adult court system until they are 18 years old has garnered great attention, but also concerns that the move will require serious tweaks if it is to do more good than harm.

In Terrebonne Parish, District Attorney Joe Waitz Jr.’s creation of an all-encompassing Juvenile Justice division aims to correct systemic shortcomings that experts say place local children at risk.

The rapid changes proposed for stale and ineffective existing systems make clear that the reforms Waitz hopes to encourage and benefits the proposed state law is designed to bring will both require tremendous work on the part of all involved if success is to be achieved.

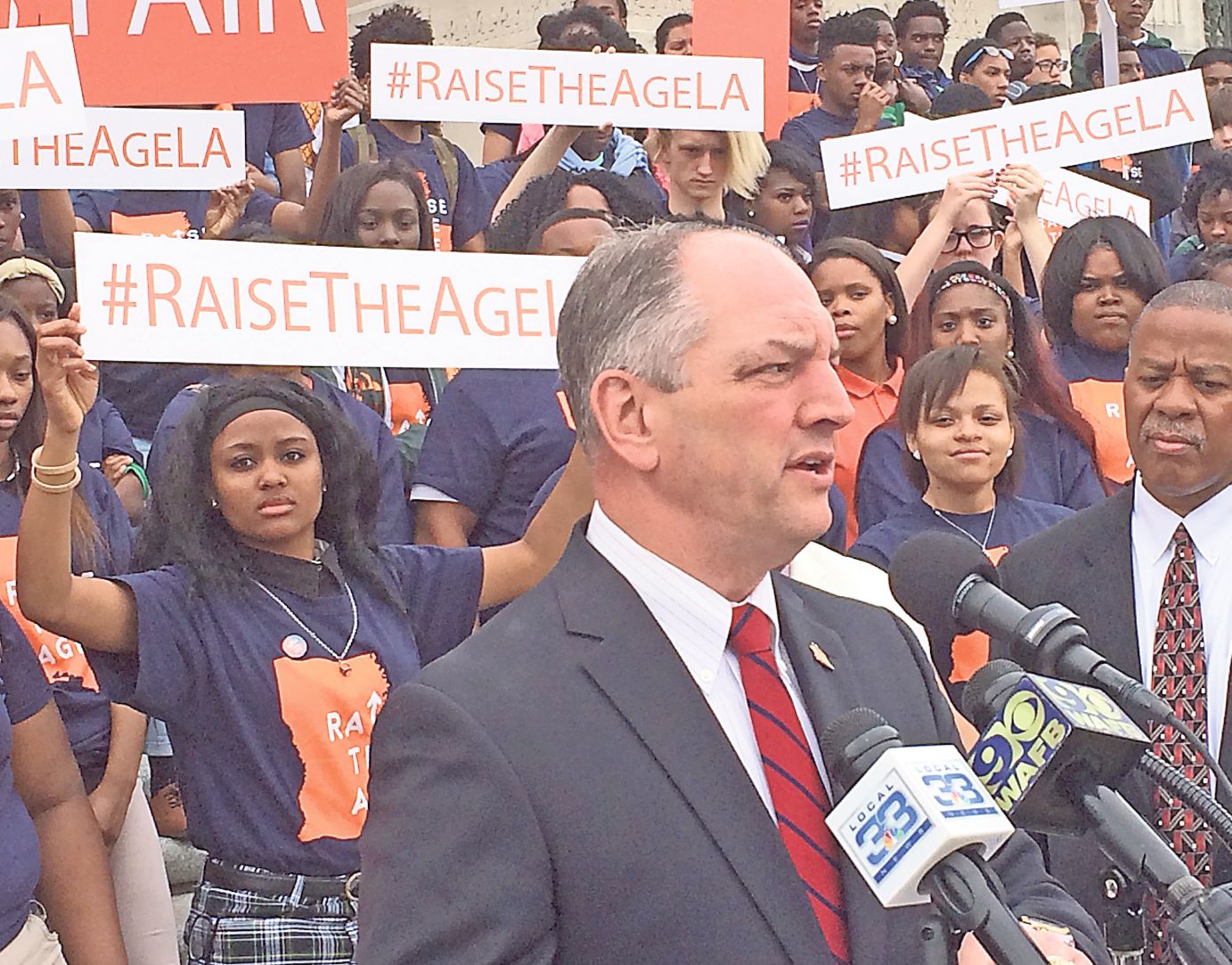

“Raising the age of juvenile jurisdiction to 18, as SB 324 by Sen. J.P. Morrell proposes, makes sense,” said Gov. John Bel Edwards, who attended a “Raise the Age” rally last week on the Capitol steps and is unflinching in his support of the measure. “In Louisiana,

adult usually means 18. Seventeen-year-olds can’t vote, serve on juries, join the military, or buy a lottery ticket. There’s only one exception: Kids are automatically charged, jailed, and imprisoned as adults the day they turn 17, regardless of their offense.”

The bill’s supporters say that if it is enacted, Louisiana will realize fiscal savings through lower recidivism and streamlined costs overall.

BETTER OUTCOMES

Forty-one states handle offenders as juveniles through the age of 17. Five of the nine

that don’t – Louisiana among them – are now considering joining the others. Last year, legislators requested that the LSU Institute for Public Health and Justice study the matter; the resulting report, issued in January, concludes that the change should be made. Positive changes in Louisiana’s once-draconian juvenile justice system, the report posits, have made success of such change more likely.

“The last several years of reform in the Louisiana juvenile justice system have created a capacity to accept, manage, and rehabilitate these youth, in a manner that will predictably generate better outcomes than the adult system,” the report states in its executive summary.

Research over the past decade that provides greater understanding of how adolescent brains develop is a key underpinning of the proposal, which maintains that still-developing brains rather than evil intent increase the potential for behavior that currently

lands 17-year-olds behind bars and sometimes in adult prisons, rather than in a more service-based juvenile system.

“Specifically, it is clear that the brains of 17-year olds are still developing, causing 17-year-olds to engage in more-risky and impulsive behavior, and this behavior is exacerbated when in the presence of peers,” the report states. “This explains, but does not excuse, why even a straight-A student, active in their community and school, can be prone to a reckless night of riding around in a car with a friend who has been drinking. Even the smartest and most responsible of youth can be clueless at the same time. They are facing an unprecedented period that combines development, opportunities for risk, and a still developing judgment process. In the simplest of terms, the brain of a 17-year-old is not fully wired and is still entrenched in the progression of remodeling itself and maturing toward adulthood.”

INCREASED RISK

The question of how – and where – teens and preteens who offend should be managed requires striking a balance between protection of the public from criminal behavior on one hand, and allowing opportunities for positive change and reformation.

Research, the report states, confirms that keeping juveniles in the juvenile justice system rather than prosecuting them as adults “enhances long-term community safety and is more likely to ensure the well-being of youth while in the justice system.”

Studies have shown that the methods now used to handle juvenile offenders 16 and under that have reduced recidivism work just as well for 17-year-olds, while inclusion

in the adult system has the opposite effect.

“In other words, processing youth in the adult system can increase risks to public safety and may fail to deter crime in the long-term,” the report states. “Research shows an approximately 34 percent lower rate of recidivism for youth being processed through the juvenile justice system. Beyond recidivism, there is a significant body of research that shows youth are safer in juvenile facilities in comparison to adult facilities.”

LSU cited a U.S. Department of Justice’s Bureau of Justice Statistics report that indicates adult-prison inmates under the age of 18 “are eight times more likely than the adult prison inmate to experience sexual abuse from other inmates while in prison … twice as likely to be beaten by staff and 50 percent more likely to be attacked with a weapon than

minors in juvenile facilities.”

The finding included a grim statistic. Seventy-five percent of all deaths of youth under 18 in adult jails were due to suicide.

WORST CASES

Support by Louisiana’s sheriffs and district attorneys will be essential, several legislators have said, if it is to have a chance of passage. So far, the reaction appears mixed, but minds are open.

An essential condition for support, according to prosecutors, is their continued flexibility to charge the most dangerous young offenders as adults when the law and circumstance allows.

“We are very concerned that with violent juveniles, we still have the ability,” said Joe Waitz, as he traveled to Baton Rouge for discussions on that bill and other criminal justice-related legislation. “We feel there are some gray areas that could create problems for the system.”

Nationwide, as in Louisiana, the majority of 17-year-olds are charged with non-violent crimes.

Marijuana possession is the number one charge that lands 17-year-olds behind bars, followed by general warrants, simple burglary, simple battery and disturbing the peace.

Locally, there are eleven 17-year-olds being held at the Terrebonne Parish jail, all booked and treated as adults.

Brandon Autement faces two counts of simple burglary of an inhabited dwelling; Raquan Williams faces six counts of simply burglary and one count of attempted simple burglary; Perry McMillen, Henry Moore and Deshawn Wolfe face simple burglary charges, with Wolfe facing an additional count of theft.

Ty’rell McKinley is charged with simple burglary as well as aggravated assault with a firearm, which is a crime of

violence. Senan Hussein is charged with armed robbery and use of a firearm;

Leroy Miles armed robbery and theft of a motor vehicle; Jayvonte Robertson three counts of armed robbery; Joseph Amacker faces three counts of armed robbery, possession of stolen things, simple burglary of an inhabited dwelling and possession of a Schedule II controlled substance with intent to distribute.

CONCERNS FOR THE YOUNGEST

Whether it is appropriate for those defendants to enter a justice system that includes 10- and 11-year-olds is among the complications being looked at hard as the legislation is evaluated. Children under 12 In Louisiana can be criminally charged in Terrebonne Parish some 10- and-11-year-olds have been housed at the Juvenile Detention Center.

Joe Harris, the center’s director, has reservations about age disparities. As there is a concern about teens mingling with adults in the regular prison system, there is a concern

about pre-pubescents being housed with the older juvenile offenders. A total of 10 children who were 10 years old were processed into the juvenile detention center in 2015. Children aged 11 years in 2015 totaled 25.

Waitz shares the apprehensions.

“We have concerns that 17-year-olds could be problems for young kids,” Waitz said. “We don’t want to expose young kids that way.”

As he weighs the wisdom of the Senate bill, Waitz is in the beginning stages of reshaping the juvenile justice system in Terrebonne Parish, now that the parish council has approved him to operate SPARC, the Single Point Resource and Assessment Center, which can be used to divert young people from the juvenile justice system altogether when warranted.

Modeled after successful programs in Calcascieu and Jefferson parishes, SPARC makes referrals to appropriate programs for juvenile offenders prior to their court appearances. SPARC is also intended as a place for parents to come with their children for referral when

non-criminal acts indicate trouble on the horizon.

SPARC’s NEW BEGINNING

Recently moved from the MacDonell Children’s Services to Houma City Court, the program is paid for by the parish as a $250,000 annual budget item. Some critics have suggested that moving the program to Waitz gives the district attorney too much power over the lives of children, and that City Court is not a place where it should live.

At one point, Waitz considered his Children’s Advocacy Center as a home for the program, or some extension of it. In an interview last week, Waitz said he wanted to make clear that accessing the services of SPARC will be free.

“I want this program to assist people at no cost,” Waitz said. “The people we are helping we are helping at no cost.” •

NEXT WEEK: EXPERTS SUGGEST LOCAL JUVENILE SYSTEM OVERHAUL