Animals adjusting to shelter

November 8, 2016

Brown sentenced to death by Lafourche jury

November 8, 2016A determined district attorney and dedicated police officers, a family with hope for closure and an inventive team of forensic scientists all combined in their own way to close out a nagging Houma cold case involving the murder of a beloved retailer 27 years ago.

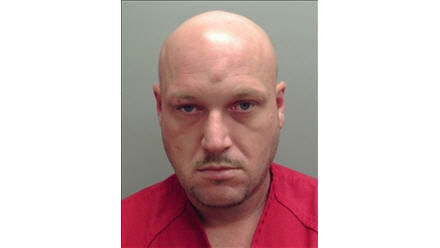

Law enforcement authorities announced last week that Bryan Wolfe, a former Houma resident who was executed for a Texas murder 11 years ago, was responsible as well for the stabbing murder of Gerald Daigle, whose body was found inside of the business he owned June 15, 1989, during a robbery.

In 2012 Terrebonne Parish District Attorney Joe Waitz Jr. orchestrated a new look at the case, which ended up involving the Houma Police Department, the Louisiana State Police Criminal Investigation Division, and the Houma office of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security. The Texas Department of Public Safety and the LSP Criminal Records Division also assisted.

“By never giving up on this case, all of the investigators from the different agencies involved performed at a level that went above and beyond,” said Col. Mike Edmonson, Louisiana State Police Superintendent. “Louisiana State Police are extremely pleased that we could assist with giving some closure to this painful and tragic memory for the Daigle family. We are also thankful for the Crime Lab that strives daily to keep up with technology. By doing so, they are able to assist with cases to help bring to justice those who commit horrible crimes such as this one that can go unresolved for years.”

For Waitz, the solution of the case had a particularly personal edge, because of one his most trusted assistants, attorney Ellen Doskey, was the victim’s daughter.

“I felt like this was a case that could be solved,” Waitz said. “I felt like the family had been through a lot and we wanted to pool all the resources possible combined with the evidence. It took a while for us to get our hands on the evidence and be in a posture where we could investigate it again.”

Lt. Bobby O’Brien from the Houma Police Department, Waitz said, narrowed the suspect field down “to one or two people.”

“He had a finger pointed at Wolfe,” Waitz said. “But they had a hard time putting it together. We had met on many occasions looking for direction, we had talked about where his investigation was going, we had discussions. There were so many different theories that were all over the place.”

Among the information picked up by O’Brien was knowledge of Wolfe’s penchant for committing robberies to support his drug habit. At the time of the murder he had an active arrest warrant for robbery.

“Wolfe was never a suspect in 1989,” said Doskey, who also too an active role in the re-investigation. “When they developed the theory the cold case team was reviewing other cases and the Wolfe name came up several times. They ran a family tree and Goggled the siblings of Wolfe.”

Those interviews revealed several key facts. His conviction – and execution – comprised one important element. Another was that Wolfe was living in Houma at the time of the murder. That led to another clue, after re-examination of Daigle’s records, which was that Wolfe had been a customer at the store. Waitz said that additionally, the $69 furniture payment information was included in paperwork Wolfe filled out to qualify for free legal assistance in a prior case.

“He actually had an account there,” Waitz said.

A pair of sunglasses found at the crime scene, Waitz said, could result in an additional link. There were fingerprints on the glasses, but at the time the murder was committed technology could only take that so far. The evidence being developed was convincing, but not enough for a definitive tie-in. The question was whether enough evidence could be linked for a prosecutor to be certain, as if the case was coming before a jury and a conviction required beyond a reasonable doubt.

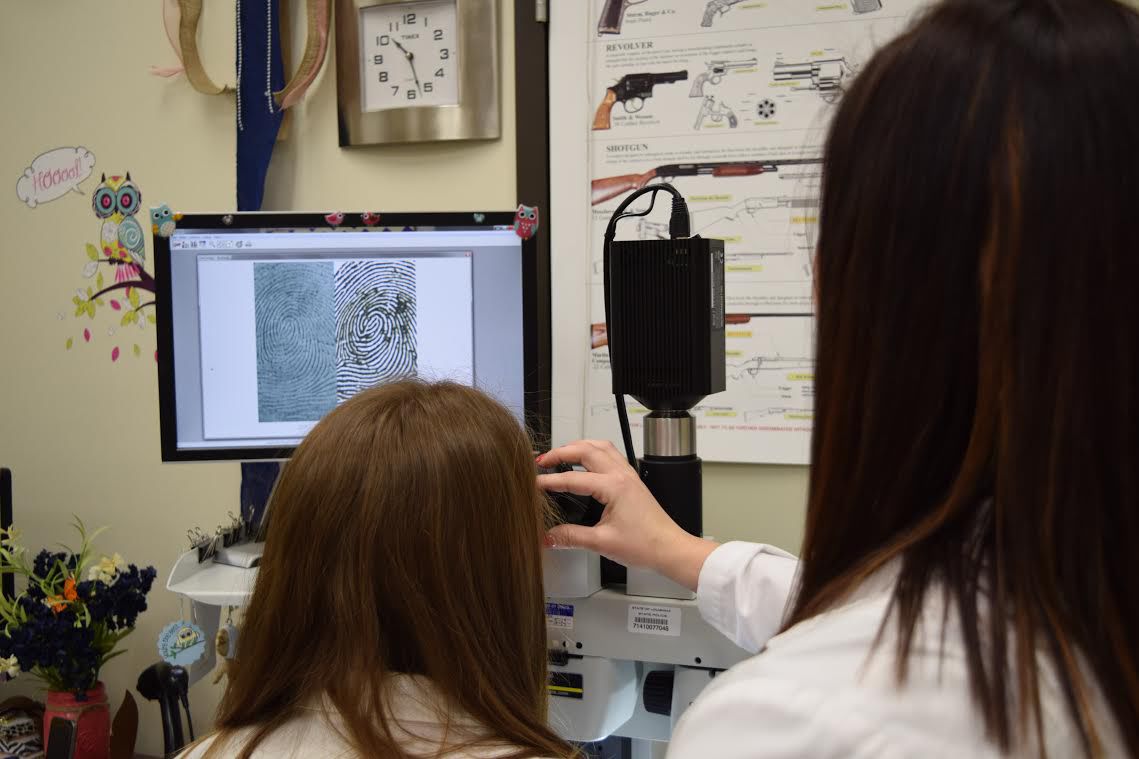

Enter the staff at the State Police Crime Lab in Baton Rouge, who found a novel way to apply basic fingerprint technology initially, and then take it to a new and novel level.

Karly Ridgell, the crime lab’s latent evidence supervisor, directed her team through the process.

“We do have additional techniques, the science has evolved and been enhanced but it hasn’t fundamentally changed,” Ridgell said. “You are looking for a known and comparing it to an unknown.”

Wolfe’s complete prints were readily available from Texas and other sources. Latent print fragments – which if properly examined can still lead to a positive result when compared to full sets – were given scrutiny.

For the highest level of scrutiny leading to the highest possible confidence, a special tool was required. Michele Cazes, a firearms examiner whose routine tasks include identifying microscopic ridges, twists and turns on shells, casings and the interior of pistol barrels, had just what the other doctors ordered. Her Leeds Olympus SZX-16 comparison microscope, enables views of two items simultaneously. The view includes a three-dimensional treatment, meaning that multiple angles could be examined.

“The comparison microscope was able to allow me to see past two levels and to the third, the edges and the pores, to get to make the identification,” said crime lab analyst and latent print examiner Melissa Goudeau. “The two stereo microscopes with the bridge in the middle allow me to see the two images at the same time.”

She and other technicians affirmed that this was the first time – to any of their knowledge – that the comparison microscope had been used in this way. They are expecting to publish their findings in forensic journals that keep others in their profession cognizant of new applications.

State Police investigators combined the already-known information with the new developments from the lab, and prepared the report that affirmed Wolfe as Daigle’s killer.

“I got a call from the State Police, that someone had come and asked if he could speak with me,” Waitz said.

A contingent had appeared from the Criminal Investigations Division. Lt. Heath Guillote, Sgt. Craig Rhodes and Trooper Justin Rice – all familiar faces to Waitz – delivered the news in the form of a report. Guillote handed it to Waitz, who immediately read through it.

“I got to the last sentence and realized, it’s him, it’s Wolfe, we got him. That’s who it is,” said an ecstatic Waitz, recalling his feelings from the moment. He leaned back in his chair and looked up at the troopers.

“Can I go tell Ellen?” he said.

Guillotte nodded yes.

Waitz knew that Ellen Doskey was working child welfare cases in District Judge Johnny Walker’s courtroom and he headed there.

“I spoke to her in the hallway and asked if I could see her when she was on her break,” Waitz said.

The break came shortly after and Doskey walked to Waitz’s office.

The case concerning her father’s murder was not in the forefront of Doskey’s mind that morning.

But thoughts of her father – and the life he lived – often are. She was 21-years-old when he was killed.

Doskey and her older sister, now married and known as Laura Ramirez, visited Daigle in the Belanger Street store often, from the time they were little girls through adulthood. Their mother, the late Margie Daigle, often brought them when stopping by.

“He was a very gentle person and that is one of the things about him, his demeanor, he was always calm,”Doskey recalled. “I don’t think I ever heard him scream or shout, even when we were teenagers and stretching the boundaries.”

Daigle’s passions, in addition to the business and his family, were running, walking and other forms of exercise, along with theater.

Producing, directing and acting in plays at Le Petit Theatre de Terrebonne – Houma’s “Little Theater” – were mainstays for Daigle. Involvement in the theater, along with his business and various civic organizations, made Daigle a well-known entity. Because of this his murder was all the more shocking to people in Houma and surrounding communities.

“We were life-long friends,” said retired businessman Ray Saadi. “From early years at the old St. Francis de Sales High School, through his time attending Notre Dame, we were friends. He was a good friend, loyal, someone you can depend on. He became Mister Theater, Mr. Director. He did things for people that nobody ever knew. He and his wife would mow grass for people who had no money to hire anybody.”

Saadi also recalls Daigle’s copious business records.

“Gerald kept a card file, every customer and what they bought,” Saadi said. “He had a marvelous memory and when you walked in the store he would pull your card and know what you had bought, what you liked.”

Saadi had been told that those copious records were a help in identifying Wolfe and affirming his guilt, and he along with other friends are relieved a resolution was made.

“This was a great, great loss and we are all glad now that there is closure and that the evidence they have convinces them he was absolutely the right man. The door can now close on this story.”

Doskey walked into Waitz’s office during her break and saw the three investigators, at first asking the District Attorney if something was wrong. He then shared the news.

“It’s not something I had dwelled on constantly but there was the feeling, the concern of what if the person who did this was someone we still see every day,” Doskey said. “That it was a relative stranger, someone we didn’t know, gives a sense of peace. It is true that with something like this you go through lots of different emotions. But there is such a thing as closure. And with that closure you can put it to rest.”

Waitz said he is hoping the resolution of the Daigle case will lead to additional work being done on Terrebonne Parish’s cold cases. The novel use of available technology by the State Police Crime Lab, he said, provides encouragement that with enough hard work and dedicated minds justice, even if delayed, can stand less of a chance of being denied. •