That delicious, home-made brew: Breweries, distilleries popping up in area

October 11, 2016

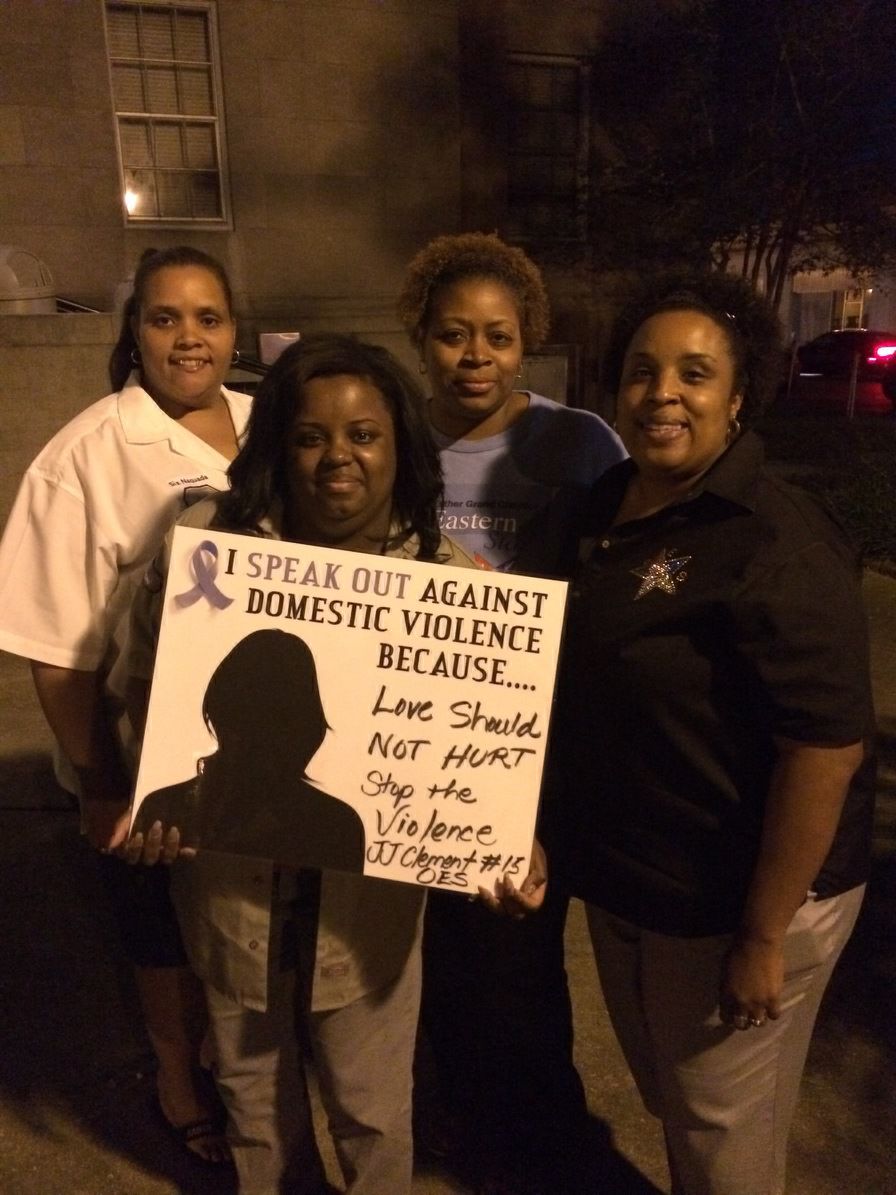

Domestic violence vigil set for Thursday

October 11, 2016That a seven-hour standoff between an armed and despondent Houma man and Terrebonne Parish deputies came to a peaceful end last week was not a surprise to Sheriff Jerry Larpenter.

“They do a good job, they train all the time,” Larpenter said. “They are motivated and they are out to save lives. We have these incidents too often to be honest with you; it’s just a shame that it gets to that point.”

He and other law enforcement officials say the Oct. 4 success story is far more representative of outcomes between police and the public than the statistically minute instances of confrontations that result in death from police action and resulting public outcry.

“They are committed to the community,” Larpenter said of his officers. “They don’t want to see anybody get hurt, nor do they want to get hurt.”

Direct observation of the incident and interviews after it was resolved result in a story of what happens when things go right, even if they start out very wrong.

The encounter began at around 6:40 p.m. on a Tuesday evening. A dispatcher at TPSO headquarters received a report of domestic violence at 134 Westside Boulevard, involving a man with a gun.

When deputies arrived they found a distraught and shaken woman whose 40-year-old husband, Jerome Amacker, had retreated into their apartment after an incident occurred between them.

Deputies determined that Amacker was alone in the apartment, that he had a gun, and that there was a good chance he would use it on himself. Quick but careful decisions were required to ensure the safety of officers, the suspect and the public at large.

“In this instance, with this individual armed with a gun, we have to make sure he doesn’t leave and harm somebody else or harm himself,” Larpenter said. “We have to defuse a serious situation, figuring out what someone may have on their mind. Do they want to take someone else with them? Does he want to die?”

Patrol deputies called for backup from detectives, who arrived with hostage negotiators. A heavily armored Bearcat vehicle – a military-style truck employed by Larpenter’s SWAT team – was dispatched with riflemen. Deputies and their supervisor, meanwhile dealt with a different type of logistics.

The small apartment building in which Amacker was holed up is in a heavily trafficked and populated area. Cannata’s supermarket, still open when the standoff began, is just across Westside Boulevard. On the same side as the apartment building is the new Walmart neighborhood grocery, and the Skateland Arena bingo hall, where games had already begun.

“You have to take into consideration the perimeter; it’s very important,” Larpenter said. “A bullet goes a long way, and there’s traffic and bystanders, and you need to make sure the person can’t escape.”

Farther down Westside are densely populated apartment complexes that generate both pedestrian and vehicular traffic. Small crowds gathered at some key spots, and deputies began to block access. An Acadian Ambulance transport unit and a supervisor set up camp in the Cannata’s parking lot, standing by in case medical help was needed.

Larpenter would not reveal the names of his negotiators, although he did give indications there may have been more than one communicating with Amacker. Initial conversations with Amacker’s relatives and information he himself supplied when dialogue began presented an immediate dilemma.

“He had called me earlier in the day Tuesday and said he was going to the doctor,” said the suspect’s mother, Mary Amacker. She knew that her son had health issues that included diabetes and heart problems that required surgery, but a new problem had arisen. She was not prepared for what he told her after the doctor’s visit. “He said ‘bye ma, I love you, I will always love you’ and he hung up. I kept trying to call him. We went over there but we couldn’t get in. From what his daughter says him and his wife were talking and she got mad and ran out the house and he said he was going to kill himself. He had a tumor on the brain and had three months to live.”

The challenge, then, involved a man distraught over an apparently shortened life, expressing willingness for life to end sooner.

A TPSO liaison communicated with Mary Amacker and other family members who remained nearby, but far enough to let officers do their work. The frightened mother saw the sharpshooters and the flurry of activity.

“I said we’ve got to pray and don’t let the devil win,” she said.

She and other relatives described Jerome Amacker as a man who had struggled with personal difficulties – including his health issues – but was a devoted husband and father. A longtime employee of the Terrebonne Parish Waterworks, he was remembered as a productive running back on the Terrebonne High football team. He was occasionally active with his mother’s church. There was a history of encounters with law enforcement as well.

On Feb. 8 he was arrested by Houma city police for disturbing the peace by drunkenness, disturbing the peace by cursing, resisting an officer and battery on a police officer.

Amacker’s unease ebbed and flowed during the course of negotiations. A close friend, identified by relatives as Cornell Fusilier, was allowed to visit with him in the apartment and for a time their conversation was productive.

Deputies, meantime, prepared for an increase in vehicle traffic once the bingo games were done, and prepared to direct those who exited into alternative routes.

The conversations ebbed and flowed in terms of Amacker’s willingness to save himself – both from his own promised actions and the potential of what police might be required to do for their own protection. At times he spoke of suicide, indicating at one point that would force the hand of law enforcement to do it for him.

At other points he expressed a desire to not leave his family with the anguish of losing him to gunfire.

“It’s going to be the decision of the suspect what the outcome is going to be,” Larpenter said. “It is not the officer escalating the problem. It’s the suspect, whether in something like this or someone being questioned while being given a traffic ticket. When your family calls and says there is trouble, the officers have already labeled it a domestic violence issue. The issue has already taken place before the police got there.”

Amacker, after several false starts, came out of the apartment with his hands raised, while SWAT officers prepared for the distinct possibility that firepower might be required. But there were no threatening moves by the suspect, and he was taken into custody without incident at around 1:20 a.m.

“I thought what they did was good,” Amacker’s mother said of how officers handled the situation. “It could have went the other way, they could have gone in and shot him up.”

Andrew Scott, a Florida-based police tactical expert, noted that the officers made good use of some intangible tools.

“In situations where there is not a hostage or anybody else in imminent danger, time is basically on the side of the police, given the scenario,” Scott said, after being supplied details of the Westside Boulevard case. “That they actually deployed their resources just in case is smart and procedurally correct. The fact that they were able to negotiate this guy out of the house is a success on every level. They acted deliberately, diligently, intelligently in this situation. There was no need to press the issue.”

Forcing the issue prematurely, said Scott, a certified expert in police procedures, can lead to the person at risk killing themselves.

“If I was their commander I would be very proud of the manner in which they handled the situation,” Scott added. “It shows good supervision in the field.”

In the current climate, where police officers in the field are faced with more public scrutiny than ever before, Scott and other law enforcement experts said, cases like the Westside Boulevard standoff have the potential to either enhance or severely damage police relations with the public. But the cases that go bad are the ones that draw the most attention.

“Statistically speaking, the vast majority end amicably, meaning there has been no violence and no rush to end the situation by violence,” Scott said. “But it usually becomes a non-news event for the media, as it is with so much law enforcement does correctly that is not newsworthy. If the outcome had been bad, it might have made national news.” •