Oil and gas future uncertain for some: Workers say they’re looking to move on from oil

September 27, 2017

Will it come back big? Only time, not spot oil guesses will tell

September 27, 2017The first thing Dane Chance and Emily Beaver mention is the weather.

Both Chance and Beaver came to Nicholls State University last fall from the Midwest. Chance, from Gary, Ind., noted the winters don’t reach the negative-20 temperatures he’s used to back home, while Beaver, from Marietta, Ohio, described the Louisiana summer as “not enjoyable at all.”

Beaver also recalled the adjustment of learning south Louisiana speech, asking her new friends to work with her untrained ear as she settled into a place she described as “like a different country.” However, the two have gotten acclimated with some time spent, particularly with the cuisine, although alligator still freaks Beaver out.

Why would two students go it alone, each leaving their families about 1,000 miles away to set up in Thibodaux? They saw Nicholls as a chance to fuel their futures. Beaver and Chance are sophomores in Nicholls’ Petroleum Engineering Technology and Safety Management (PETSM) program, preparing to be leaders in the energy industry once they graduate.

Nicholls’ PETSM department has been preparing generations of oil and gas workers for more than 40 years. The department, led by Department Head Dr. Milton Saidu and Executive Director Michael Gautreaux, leads students on a path to earn associate’s and/or bachelor’s degrees in either petroleum services like exploration and production or safety technology.

Gautreaux said the NSU PETSM program has grown significantly over the last decade, but the oil glut has taken its toll over the last three years. According to Gautreaux, total enrollment in the PETSM program was around 150 students in 2006. Nicholls started to add students at a blistering pace, tripling its enrollment by 2014 to around 450 students, according to Gautreaux. That number has since dropped considerably, with about 300 students in 2017. Gautreaux said some freshmen may be leery to join the program when the current local state of oil and gas is so bleak. However, students attending the program expressed confidence in the future of petroleum, and PETSM professors extolled the opportunities still available to current and recent students in the program.

The NSU PETSM program has student chapters of three oil-and-gas-related professional organizations, including the American Society of Safety Engineers, the Society of Petroleum Engineers and the Association of American Drilling Engineers. Michael Vinzi, a 1991 graduate of the PETSM safety program and now a safety professor at Nicholls, said those organizations help students make connections to both cultivate job opportunities and get a better hold on what work is like in the field.

“You learn about subject matters in class, but those organizations provide chances where you really talk to somebody about what they do, and they tell you, ‘Oh, I do this, I do that,’” Vinci said.

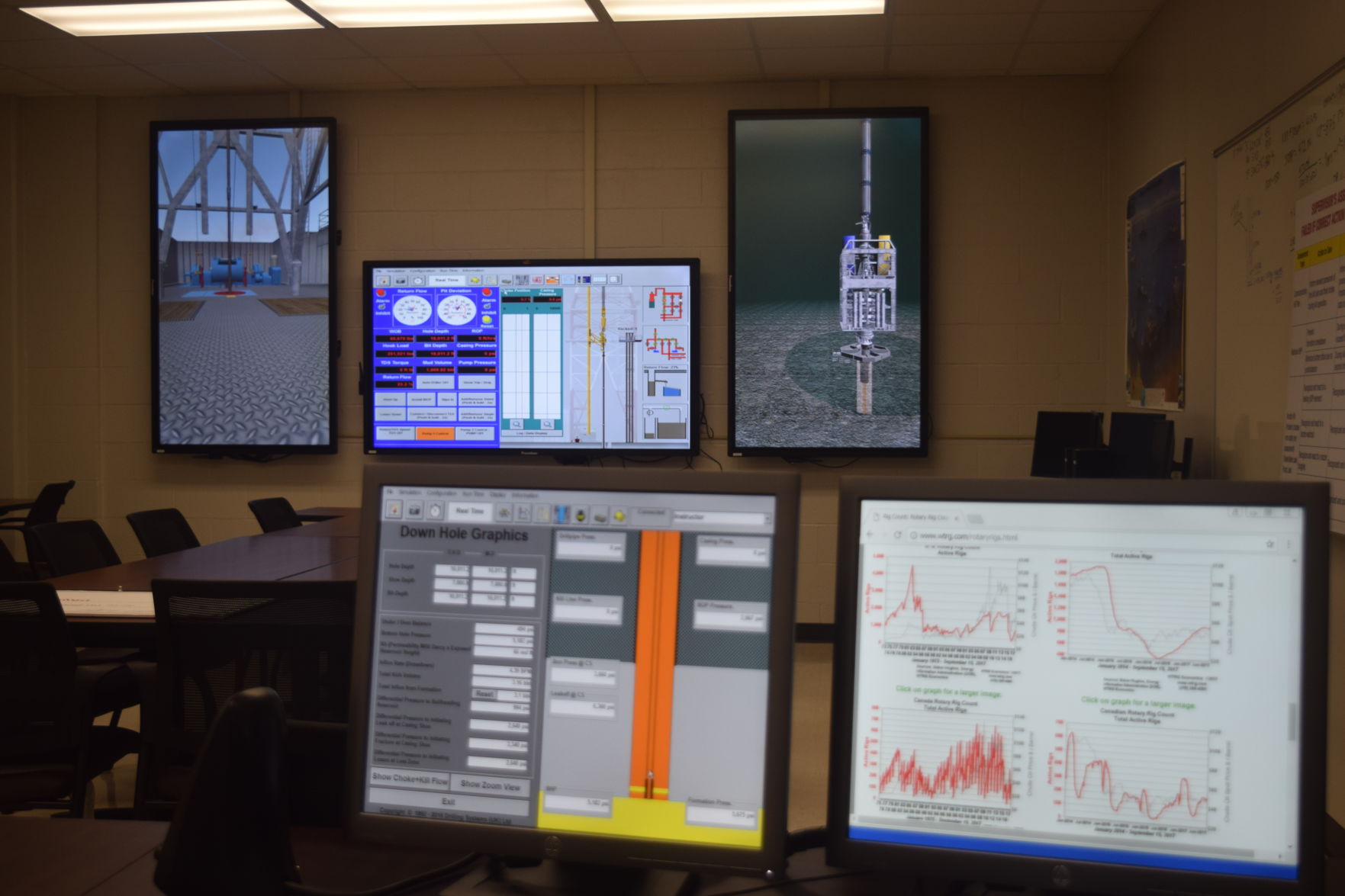

To prepare Nicholls students to capitalize on those opportunities when they pop up, the university has made considerable investments in training technology. In the fall of last year, NSU acquired a drilling and well control simulator from Drilling Systems. According to Gautreaux, the simulation software cost about $250,000 total for an instructor version and five student versions when including the renovations to the simulator room at Gouaux Hall. According to Gautreaux, PETSM classes would take field trips up to spend time on Louisiana State University’s well control simulator before Nicholls got its own.

Students take the simulator course in the spring, typically splitting into two classes of 30. They get weekly lessons from Dr. John Griffin and then take two-to-three-hour sessions on the simulator. Griffin said the software lets students practice exploration drilling and maintaining the flow of oil. They can get different views of the well, seeing what a driller sees on the surface and what it looks like downhole. As on a real oil well, they are required to operate the pump pressure and the well’s choke according to a predetermined table of pressure vs. choke rate specific to each well. The simulator speeds up the time elapsed compared to real time, slowing down to real-time when a problem, presented by either Griffin or the simulator, springs up.

That problem manifests as a “kick,” a bubbling of gas that can enter the drilling pocket. Students are trained to notice the gas migration and properly adjust the pressure and choke to get the gas out of the pocket. They can adjust the pressure before utilizing a virtual blowout preventer to prevent catastrophes like the one that started the BP oil spill.

Griffin said most students typically get comfortable with the simulator around the third time on it. While they are only virtually adjusting pressure and choke rate as opposed to physically doing it on a well, the real-time experience is critical. Griffin likened operating a well’s pressure to driving a car, noting novice drivers will often turn left or right too powerfully at first before becoming comfortable with slighter, nuanced steering. Griffin said the simulator at Nicholls gives students a chance to foster that same kind of hand-eye coordination before they step on a real well.

“The student learns on a simulator, by messing with the choke a little bit, he can tell when it actually opens. That right there teaches him about mechanics. That’s something you can’t do without a simulator,” Griffin said.

Gautreaux compared the well control simulator to a flight simulator, saying those who spend time on one may not be ready to fly around the world tomorrow, but they are more prepared to fly a plane than the majority of the population.

“When somebody leaves here they’re not an expert in [drilling], but they’re exposed to it,” Gautreaux said.

Chance already has some experience under live rounds. He spent the past summer on a workover rig as a roughneck. Chance said while he was glad to get some experience, the work lived up to the job title.

“[Roughnecking was] hard,” Chance said. “I know why I want to get my degree now!”

While Chance and Beaver are students from out of state, they seem to be exceptions to the rule at Nicholls. In a recent safety class taught by Vinzi, Chance and Beaver were two of only a few out of about 30 who came from out-of-state. Most students identified as from the Bayou Region, with the rest from South Louisiana.

That safety class, and the safety program at Nicholls, is another avenue of opportunity for current students. According to Vinzi, the benefits of safety work is that it is not confined to any particular part of the oil and gas production line, nor is it limited to the energy sector at all. He said while drilling and production focuses on the upstream part of the oil and gas supply chain, safety work is needed not only there but also in midstream work such as pipelines and downstream facilities like refineries and plants. That appeals to Beaver, who is getting a bachelor’s in petroleum service and an associate’s in safety and said she would like to combine the two for a position as a safety supervisor for an oil company. Vinzi said he has also seen a recent graduate get hired by Amazon to help coordinate safety in their supply chain, as the overall principles and culture of safety are marketable across the job market.

That versatility is why Jesse LeBlanc is getting a bachelor’s in safety. LeBlanc, a Houma native, is transitioning into the workforce full-time after 18 years with the United States Army National Guard and the National Guard Reserves. He said he previously spent five to six years working in the oilfield, working his way into production before deployments overseas. Now he lives in New Orleans and comes to Nicholls once a week for two classes, taking the rest online to have a full-time course schedule. LeBlanc said he misses the camaraderie of the oilfield and is getting his degree so he could combine his training and supervisory skills.

“I’m from Houma, so I’ve grown up around oil and gas, but where I live at, there’s a lot of plants, refineries and things of that nature out there,” LeBlanc said. “I think my options would not be limited, and that’s why I chose this program.”

Vinzi talked about the keys to being successful in the safety business, noting his current business as a safety consultant. He said many workers are wary at first of a “safety cop,” but the key is letting them know they are there to help and work with them and not write endless tickets.

“In the safety career field, communication and how we communicate related to people is a huge factor,” Vinci said. “If you come across – yeah you have a job to do, but there’s a way to talk to people about, educate.”

Vinzi’s real-life experience is how he ended up teaching at Nicholls, starting with online classes as an adjunct six years ago before becoming a full-time professor three years later. He said Gautreaux contacted him about teaching because he wanted not just professors with Ph.D’s but also those who could pass on applied knowledge to students.

Nicholls also accommodates students getting their own real-life experience while they continue their education. The PETSM program has flexible scheduling for those working seven-on, seven-off or 14-on, 14-off schedules offshore. For those working on seven-day schedules, Nicholls offers the same PETSM classes on Tuesdays and Thursdays of the week. A student coming back from offshore work for a week on Wednesday can attend that Thursday class and then the next week’s Tuesday class before going back offshore, returning to attend the following Thursday class and not missing any lesson. With all general education courses at NSU available online, students can maintain a full-time course load while earning and learning offshore. LeBlanc said that flexible scheduling helped bring him to Nicholls, as he would not have to pass up a job offer because of his class schedule.

“If an opportunity does come up, I’m already in a position where it will not conflict with my school,” LeBlanc said.

While the oil industry is currently hurting, Beaver, Chance and LeBlanc maintain optimism in its imminent return to strength. That confidence extends to the faculty at Nicholls, with Gautreaux saying there is still a load of untapped potential in Gulf of Mexico oil exploration. Gautreaux said as the price of oil rebounds, Nicholls students will be primed to capitalize in the Gulf and elsewhere due to the work they put in at Thibodaux.

“Almost today to get a job and operate you need a degree. It’s not like it used to be years and years ago, if you can work hard you can get a job,” Gautreaux said. “The skillsets and the competencies and the job require critical thinking and leadership in this industry that we’re in.” •