Tuesday, Dec. 13

December 13, 2011

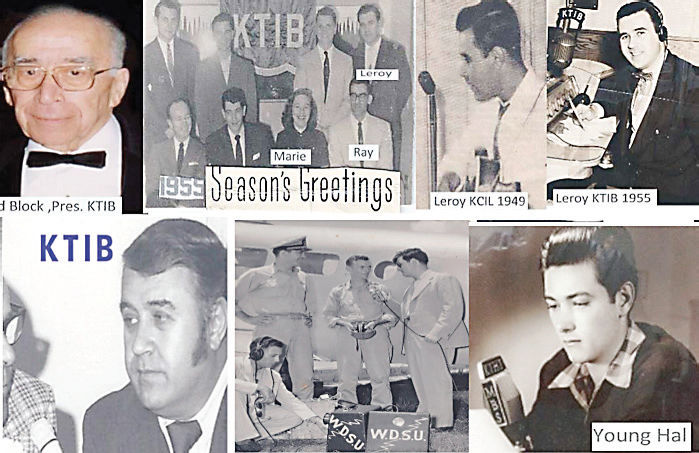

Hubert P. Rivere

December 15, 2011The rapid growth of cities in the 19th century meant more jobs, more businesses, more of almost everything, including fires.

One city that saw tremendous growth, particularly immediately after the Civil War, was Chicago. Construction was a booming business. No less than 7,000 buildings were erected in 1865 alone. Most of the homes and a fair number of city structures were made of wood, about 36,000 out of 39,000. Even the streets were made of pine, 561 miles of them. Housing was jammed, living conditions were less than ideal, and fires were quite common, 700 fires in 1870 alone.

No fire, however, received as much publicity as Chicago’s Great Fire of 1871. It was more than a fire; it was a media event. All supposedly caused by Mrs. O’Leary’s cow.

No one knows how the fire really got started, but once it began it looked as if it would never be put out. From Sunday, Oct. 8, to Tuesday morning, Oct. 10, the fire raced through the city, in part because of the overuse of wood as a building material, a drought in the area and a wind that blew the fire east to west into the heart of the city.

On Monday night the rains came and thankfully put out the blaze by morning. By then the elaborate homes near the center of the Chicago, as well as the business district, consisted of the ashes of the opera house, Chicago’s City Hall, hotels and other businesses and the elaborate mansions for which the city was famous.

More than 200 people died in the fire and 90,000 people were left homeless.

Poor Catherine O’Leary was blamed for the fire, in part because she was Catholic and an immigrant, a bad combination in 19th century America.

Years later, however, the reporter who originated the story about the O’Leary cow knocking over a lantern and starting the fire admitted the story was a fabrication.

The fire destroyed all of the original foundation of the growing young city. However, Chicago strangely benefited in the aftermath of the fire. Architects from around the country saw an opportunity to demonstrate their work through a new urban design. Frank Lloyd Wright’s brilliant designs, for example, serve as a tribute to a city that refused to die.

Even the Chicago Tribune, in a new “fireproof” building, burned down. Horace White, then editor of the Tribune, wrote the following letter that was printed in the Cincinnati Commercial.

“… Once out upon the street, the magnitude of the fire was suddenly disclosed to me.

The gods of hell were upon the housetops of LaSalle and Wells Streets, just south of Adams, bounding from one to another. The fire was moving northward like ocean surf on a sand beach. It had already traveled one eighth of a mile and was far beyond control. A column of flames would shoot up from a burning building, catch the force of the wind, and strike the next one, which in turn would perform the same direful office for its neighbor. It was simply indescribable in its terrible grandeur. Vice and crime had got the first scorching. The district where the fire got its first firm foothold was the Alsatia of Chicago. Fleeing before it was a crowd of blear-eyed, drunken, and diseased wretches, male and female, half naked, ghastly with painted cheeks, cursing and uttering ribald jests as they drifted along.”

In the end, the fire destroyed a swatch of Chicago that measured about four miles long and almost a mile wide.