Bill advances to ban gender-affirming care to minors

June 3, 2023

Boston College powers past Colonels in NCAA Regional

June 3, 2023By Claire Sullivan

LSU Manship School News Service

He paced the Tiger Stadium sidelines, gave rousing locker room speeches and traveled with the football team. But this unofficial coach could not leave Louisiana without temporarily giving up his gubernatorial powers.

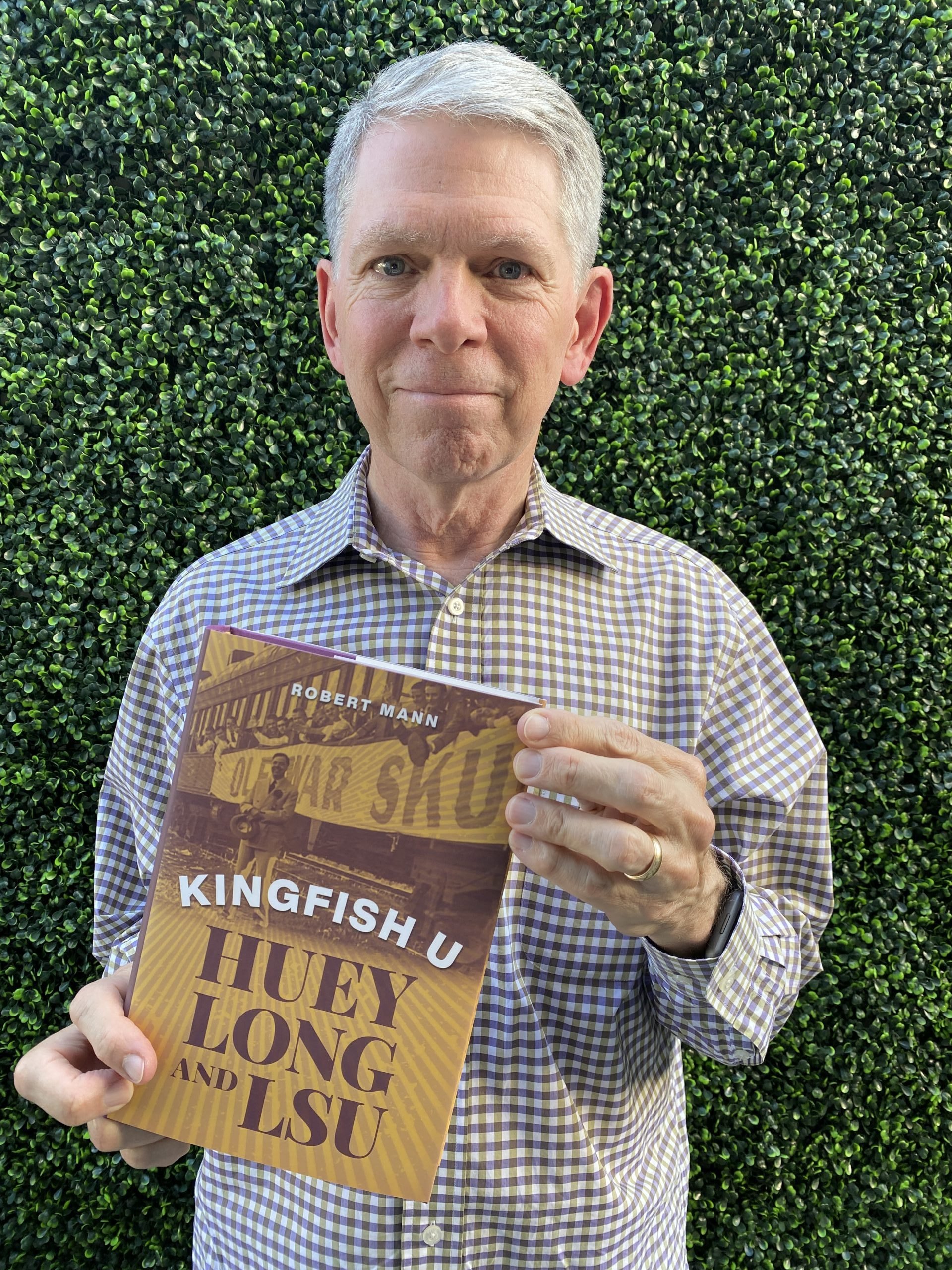

In a new book, “Kingfish U: Huey Long and LSU,” LSU professor Robert “Bob” Mann documents the intense relationship between former Gov. and U.S. Sen. Huey P. Long and the university he helped build into its modern form.

An unofficial football coach, Long also acted as the university’s de facto co-president and a member of the LSU Board of Supervisors. Though he never attended LSU, and was once its opponent, Long set the university on a new path to national recognition.

Long helped expand the campus and bolster enrollment, increasing state funding for the university and opening its doors to students from more economic backgrounds. (Though, at the time, still only those who were white.)

But, akin to Long’s political endeavors elsewhere, his successes at LSU were brought with censorship, questionable financial dealings and intense oversight of faculty and students.

“He did the greatest things in the worst possible ways,” Mann said in an interview.

This is Mann’s ninth book, and one that strikes particularly close to him, not just as an LSU professor but also as a former staffer and biographer of Huey’s son, U.S. Sen. Russell Long.

The book is being released by LSU Press on Wednesday.

In the early days of the pandemic, Mann launched into the project as he finished another book, “Backrooms and Bayous: My Life in Louisiana Politics,” which chronicles his time as a communications professional for Louisiana politicians in Baton Rouge and Washington, D.C.

For this book, Mann dug into unused notes from the Pulitzer Prize-winning Long biographer T. Harry Williams, papers from students with close connections to Long and newspaper and university archives.

Though Long would eventually help propel LSU from “mediocrity to near-excellence,” Mann wrote, his first interest in the university was in its football team.

Long began showing up at team practices in 1928. And in 1929, he began meddling in recruitment, trying to entice a star player from Centenary College to Baton Rouge with a $125 per month job at the state laboratory and an $80-a-month job on campus.

Though Long involved himself in the program, Mann wrote, he “knew little about the intricacies of football.” He had remarked to the coach at a practice before the 1928 LSU-Arkansas game that Arkansas must be kicking off this year since LSU had done it the previous year.

At the 1930 LSU-Tulane game, “an out-of-state visitor to the stadium unfamiliar with Louisiana politics and college football might have mistaken Long for LSU’s head coach,” Mann wrote. Long even took some credit for LSU’s performance (a celebrated loss).

“Well, I did my damndest, anyhow,” Long told the press after the game, Mann wrote.

But Long did not need to be a football mastermind to reap its political benefits.

On the sports pages, Long found a better chance for positive coverage than he did in the news section. And his relationship with the team allowed “voters—in Louisiana and beyond—to see him not just as a political figure but as a cultural icon,” Mann wrote.

As in his political life, Long wanted to be seen as a winner. “LSU can’t have a losing team because that’ll mean I’m associated with a loser,” one quarterback recalled Long telling the team, Mann wrote.

But Long’s interest in the university did not remain exclusive to football. And his involvement, and suspected meddling, did not always earn him positive press.

One incident that caught national attention was the 1931 firing of John Earle Uhler, an English professor who had written a novel set on LSU’s campus that a local Catholic priest found unsavory. Uhler was fired, a move supported by LSU board members, including Long.

Some suspected, though, Long had ulterior motives to want Uhler out. The professor had testified against a favorite student of Long in a criminal libel trial the year before.

Mann, a tenured professor at LSU’s Manship School of Mass Communication, said he felt a certain connection to Uhler. Attorney General Jeff Landry, now running for governor, demanded in December 2021 the university punish Mann after he called Landry’s assistant a “flunky.”

“I do identify with Uhler somewhat,” Mann said. “And, you know, Uhler didn’t have tenure.”

Though Long’s legacy at the university is marked by displays of censorship like the Uhler firing, he also is credited with helping to usher the university into a new age of prosperity. With near-daily phone calls and visits to the university, Long regarded it as a high priority.

But Mann thinks Long would be “horrified” by modern LSU. The university suffered under budget cuts during Gov. Bobby Jindal’s administration and has more than half a billion dollars in deferred maintenance needs.

“Huey Long would have found a way to build a new library within a couple of years,” Mann said referring to the building’s infamous leaks and deterioration. (Though, Mann added about the current governor, John Bel Edwards, the way Long “would do it probably wouldn’t be the way I would suggest Gov. Edwards to do it.”)

Though Mann does not wish to see a return of Long’s undemocratic tendencies, he thinks Long’s can-do attitude is missing from Louisiana politics today.

“I hope this book is a reminder that, if state leaders desire, they can make LSU great again, and quickly,” Mann wrote.