5 Tips to Lower Your Risk for Hypertension

August 1, 2019

Lafourche Booking Log – July 31, 2019

August 1, 2019This is what I remember. I was born. I was in the air upside-down. Someone slapped me on the backside. I felt the sting on my skin. My eyes opened. Through a slant of light between curtains, I could see images beyond a window. The ground outside was covered with white shells. I relaxed for a moment as the sting subsided, and then I retaliated against my slapper in the only way I could. Then I closed my eyes and cried. That’s what I remember.

Now, normal humans can only remember things as far back as around two-years of age. And, despite all else, I’d like to be known as normal. So, years later, I would verify that a large shell parking lot lay behind the hospital where I was born outside the rear of the building where the maternity ward had been at that time. And so, it all made sense: Like many in PoV country, I was born into a world of shells.

Even at age two, I can remember when people would visit our Golden Meadow home where I was the youngest at the time. I remember the crackly, grinding sound of shoes or tires as visitors walked or drove across the bed of shells between the asphalt street and our concrete driveway. It’s a distinct sound—much more high-pitched than if you’re crossing gravel, as if the spirits of all those sacrificed oysters and marsh clams cried out at once. And so, it all made sense: gravel grinding is a deep, less-crackly sound not at all like crying because, unlike the mollusks that made oyster and clam shells, the rocks that made gravel were never alive.

Shells are part of our heritage in PoV country. Native Americans in past centuries left us artefacts that show us the availability and importance of mollusks in their environment. The marsh clam Rangia cuneata and the Eastern oyster Crassostrea virginica are major finds in the shell middens left by those early communities as remnants of their diets. Even in more modern history, many a public servant’s worth was once measured by how he could deliver a truckload of shells on demand.

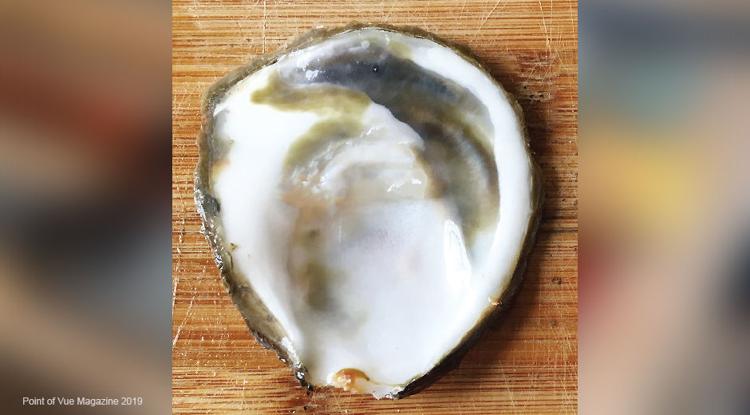

In the early 20th century, Terrebonne and Barataria Bays grew oysters that were a country-wide delicacy. Canned and shipped locally and in New Orleans, these celebrated “cove” oysters were renowned for their saltiness and fleshiness. Earlier, sixteenth-century Spanish explorers mapped mile-wide oyster beds off the Lafourche and Terrebonne coast and, by anchoring on the mainland side, used them as ramparts against the onslaught of tropical storms from the Gulf. Even Nobel Prize-winning author John Steinbeck, when traveling through Terrebonne and Lafourche along U.S. Highway 90 in 1960, called roadside homeowners “shell-heap Cajuns,” referring to the oyster shells piles in their yards that grew after each meal of the delicacy.

The coastal estuaries of southeast Louisiana were once home to the world’s largest population of marsh clams. Before getting paved in the 1930s, dredged marsh clam shells formed our roads, as they stretched for the first time along the natural levees of all our bayous toward the coast. Everyone likely has a memory or at least a family photo of driving along a rippled and noisy shell road en route to coastal beaches and docks and marinas, leaving behind a heavy cloud of white dust in their wake. When those roads were finally paved, the clam shells were used as aggregate in the concrete and asphalt mixes. And marsh clams have been here a really long time: Dredging operations along the latitude of Thibodaux and farther north raise bucketfuls of marsh clams from 25-feet below, reminding us of where coastal estuaries existed while the Mississippi River created Bayous Lafourche and Terrebonne over the course of 1000 years.

Back when I was learning things like the alphabet, numbers, and the names of months, there were only eight months per year in my world, and they all had the letter R in their names. Those were the months when Gulf oysters were good and safe to eat. (And for you Texans who still eat them canned as “little necks,” the same was probably true for eating marsh clams.) But despite being born into a world of shells, the whole back porch parental operation of shucking oysters was one distasteful mess for a two-year-old. Smelling them cooking wasn’t appealing either. I would have rathered just listening to cars drive over them. It took many years of palate maturation for me to appreciate the smell and taste. Nowadays, I appreciate them in any weekday that ends in Y. At some point in life, you just gotta open your world with a blunt knife and appreciate the juiciness of your heritage.