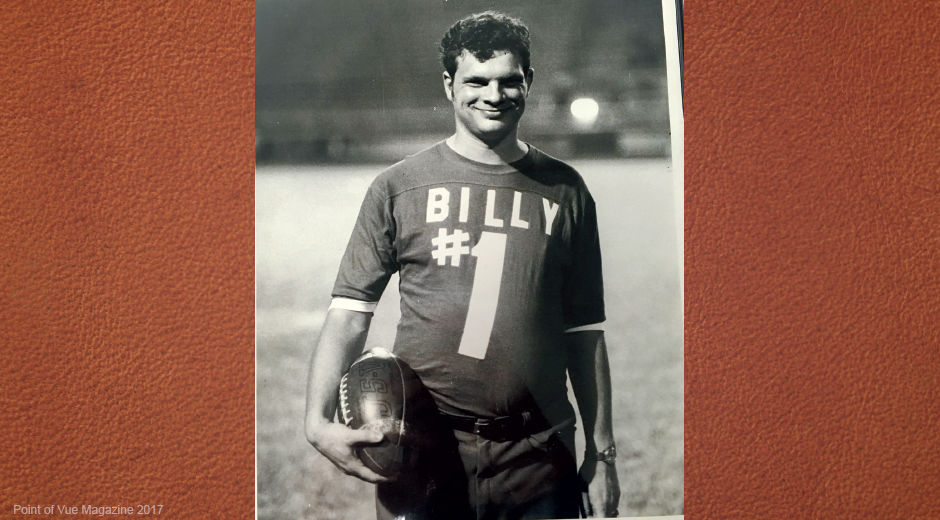

A Lifetime of Selfless Service

November 1, 2017

Heroes Among Us

November 1, 2017A dog catcher for Terrebonne Parish. A teacher in Brooklyn. An actor in a traveling act. A Peace Corps member in Tonga. A grant writer in Bangladesh.

No, this isn’t an international league of pen pals. These are just a few of the startup versions to one of our own who’s gone far and wide only to return and help preserve his home.

Jonathan Foret was born in Chauvin to a dad from Cocodrie and a mom from Chauvin. He recalls his mother being part of the generation who would receive the paddle for speaking French at school. He grew up running through the woods with friends to the levees and the marsh, long before it was just a destination to get to and immediately share on Instagram. After Hurricane Juan hit in 1985, the Forets drove around to find the highest land, ending up in Bourg.

“Within my own family’s progression, when we talk about land loss, my own family has migrated north,” Jonathan said.

While Jonathan enjoyed his time playing with friends on the bayous, he also did a lot of growing up. His father was in the oil industry and would trawl whenever he was back onshore. Jonathan would go out on the boat with him and help, trawling and picking shrimp, which gave him some spare cash to buy stereos and pellet guns.

“My parents were teaching me lessons that I wasn’t even aware that they were teaching me just about working, saving money, buying things that you want and taking care of those things,” Jonathan said.

Jonathan left his English studies at Nicholls State University and applied for and got into an conservatory in New York City. He spent two years as an actor, traveling across the country and playing shows; by his own estimation he’s seen about 48 of the country’s states. Jonathan then became a teacher in Brooklyn.

After two years of teaching, Jonathan wanted to see the world and continue to make a difference. He decided to join the Peace Corps. Jonathan let his students at school do projects on different countries around the world and ultimately left it up to them to decide where he would ship off to. They chose the Kingdom of Tonga, a Polynesian state composed of almost 170 tiny islands, because it “had a lot of water” and “the beach was nice.”

Jonathan served as an English teacher on the Tongan island of Mango. There was no electricity, no cars, no corner stores on Mango. What he ate is what he and his island mates caught from the water. One day he was clearing bush to build a fence, and the bush knife ricocheted off a branch and went into his leg, slicing open a bloody gash. He hobbled back to his tiny house and asked for an hour boat ride to Nomuka, a larger island with someone who could do medical care. Jonathan’s best friend on Mango brought him the next day to a woman who was known to do stitches. The woman didn’t ask for Jonathan’s name or insurance. She just saw he needed stitches, so she gave them to him and sent him on his way.

Jonathan rode out a cyclone on Nomuka, returned to Mango, and when his time with the Peace Corps finished up, he came back home. He had to deal with the culture shock of walking into a Wal-Mart on the ride from the airport after two years’ spent with none of the creature comforts known here. Jonathan was unsettled by the different way of life he had grown up in and needed time to adjust back, which he credits patient family and friends with giving him the space to do so. With more time separated from the jarring life changes, Jonathan is thankful for the experiences he learned at Tonga, where he was able to discover who he was on a foundational level.

“I remember what it gave me. And I’ll never lose that, but now I can operate with it in a place that is within me but does not make me unable to function, ‘cause it did for a little while,” Jonathan said.

After returning home and re-adjusting, Jonathan started looking for work. He knew how to write grants from his Peace Corps days, so he looked at nonprofit work in the Houma area. He was hired as the executive director for the South Louisiana Center for the Arts before taking over in the same role at Southdown Plantation. He was soon across the globe again, working in Bangladesh with an organization developing an economic program for people with disabilities.

Jonathan came back from Bangladesh and got his master’s degree in public administration from the University of New Orleans. Seven years ago he became the executive director of the South Louisiana Wetlands Discovery Center, where he works to this day. The SLWDC educates the youth about the challenges Louisiana faces with a rapidly eroding coast in the hopes of helping them make informed decisions about their futures – be it building sustainable, elevated housing down the bayou or finding a place less threatened by water.

“I want them to have a realistic perspective of what the future could be,” Jonathan said. “Multiple scenarios – some very good scenarios, some not so good, and what are you going to do in between?”

Jonathan credited the board at the SLWDC for its support and vision in bringing awareness to the threats facing this unique area faces. He and the center have also been promoting the human and cultural treasures of the area over the last five years through one of the most festive and family-friendly weekends of the year. The Rougarou Festival, held in October of every year, is Jonathan’s brainchild and a celebration of all things South Louisiana. It is a yearlong community-preserving event, where people come together to pick berries, tell stories and make gumbos and meals to serve at the festival. People come from across the country to attend the festival, which features kids’ activities, storytelling, the Krewe Ga Rou costume parade and much more.

Jonathan said he received a message about a woman who grew up in Chauvin but now lives in North Carolina who is attending the festival this year. The woman told Jonathan about not only her own excitement but that of her five-year-old daughter.

“This little girl, whose mom is from Chauvin, gets to come and eat a beignet that her mom’s people cooked. And have gumbo and hear stories of the Rougarou. Because that’s a piece of her culture, and she’s not experiencing it in Asheville, but they’re going to come and experience that together,” Jonathan said. “When I say our volunteers are the keepers of our tradition, with more and more folks moving out, there’s got to be a core group of people who are going to carry the torch.”