Succulent savvy!

June 1, 2021

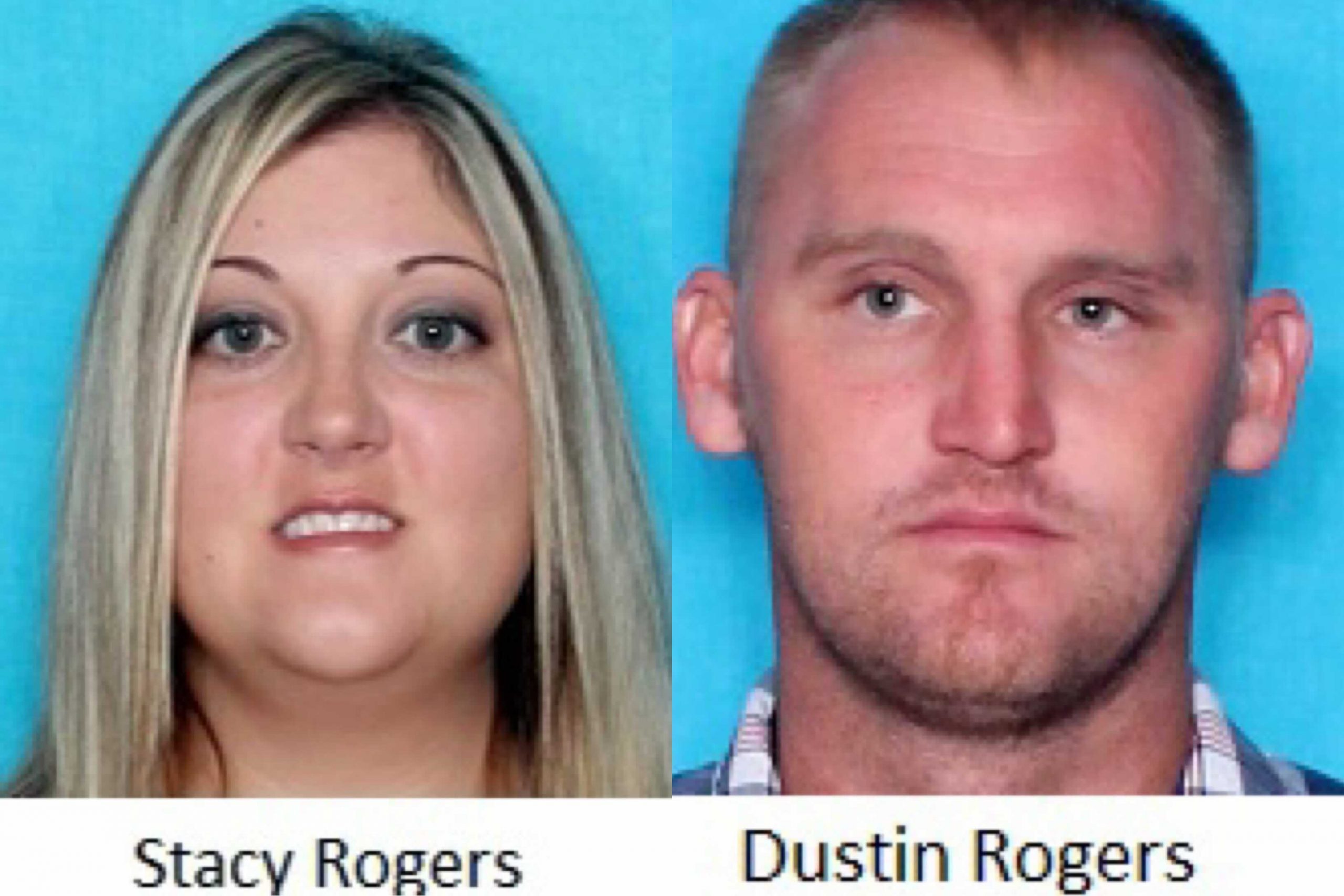

Couple charged in Rusty Pelican Bar crash, police say

June 1, 2021LSU AgCenter researcher Kristen Healy understands the delicate balance of protecting loved ones and pets from the dangers of mosquito-borne illnesses, while also ensuring the safety of the honey bee population, which provides a significant food source through pollination. This was the basis of the May 25 online presentation she conducted via Zoom and Facebook Live.

As part of the “At Home Beekeeping” series, co-sponsored by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), the Lawrence County Alabama Extension Office, and multiple universities, Healy presented the live webinar, “An Evaluation of the Effects of Public Health Pesticides on Honey Bees.” The presentation delved into lab, semi-field and field studies that were conducted to determine negative impacts, if any, of various mosquito-abatement pesticides on the honey bee population.

Healy, a medical entomologist who came to the AgCenter in 2013 primarily to work with mosquito control, said one of the first issues she encountered was from beekeepers who were concerned about the effects various methods of mosquito control might have on honey bees.

“Brand new to LSU, I was asked to take on this controversial and interesting topic,” Healy said. “I didn’t know at the time that Baton Rouge had the USDA Honey Bee Breeding, Genetics, and Physiology Research Lab right down the road.”

She said mosquito control exists for a reason. Prior to inception, hundreds of thousands of people would lose their lives to diseases each year in the United States alone. According to the American Mosquito Control Association, illnesses such as Malaria, Dengue and the West Nile virus still annually kill more than one million people worldwide and others harm animals like Eastern equine encephalitis in horses and heartworms in dogs.

“Even to this day, every 30 seconds a child dies from malaria,” Healy said. “But, of course, pollinators are important as well. One out of every three bites of food we take relies on bees. So my goal in research is assessing how we balance everything for a healthier environment.”

The past few years, Healy and her associates have advocated for improved communication between pesticide applicators and beekeepers. In addition, they conducted studies that looked at other stressors to honey bee health and found that Varroa mites and the pathogens they transmit have more deadly impacts than do mosquito pesticides.

She is quick to emphasize that science should be conducted in an unbiased way. She wants to make sure that even though her background is in mosquito control, she works in collaboration with the beekeeping community so that all stakeholders have a hand in designing and conducting experiments.

Healy’s research looks at risks of both toxicity and exposure combined. She said if viewers of her presentation can walk away with one thing, it’s that the dose makes the poison.

“Anything is toxic when it meets a certain concentration,” Healy said. “You can consume too much table salt and you could die; it’s the same with sugar. You could even die from consuming too much water. In a laboratory, we can assess toxicity and determine the pesticide dose that could kill a honey bee or any other organism.”

Healy’s full presentation can be seen until June 9 on the Lawrence County Alabama Extension Office Facebook page.