LHSAA releases High School Football Playoff Brackets

November 6, 2022

Join CIS for the Great American Smokeout on Nov. 17

November 7, 2022By Drew Hawkins, Adrian Dubose, Allison Allsop and Alex Tirado, LSU Manship School News Service

Third in a four-part series

At 12:35 p.m. on Nov. 17, 1972, the phone rang in the office of acting FBI Director L. Patrick Gray in Washington.

It was Deputy Attorney General Ralph Erickson, calling to order an investigation into the shooting of the two students at Southern University amid a cloud of tear gas 25 hours before.

FBI officials quickly made plans to send dozens of agents from across the country, including some who had investigated shootings at Kent State and Jackson State. The first group arrived in Baton Rouge two days later, setting up in the Capitol House Hotel, a white-painted, square brick building downtown.

“It took us just overnight to set up the office,” said Jack Stoddard, an agent from Philadelphia. On Monday morning, Nov. 20, he said, “assignments were given out.”

Within three days, the FBI knew that the students, Denver Smith and Leonard Brown, had been killed by a single blast of buckshot – and that the shot had likely been fired by one of the East Baton Rouge Parish sheriff’s deputies near a palm tree in front of the school’s administration building.

Medical examiners removed 17 tiny shotgun pellets from the men’s bodies. Three more pellets had dented the wall of the building right behind where the men were hit as they ran from the tear gas.

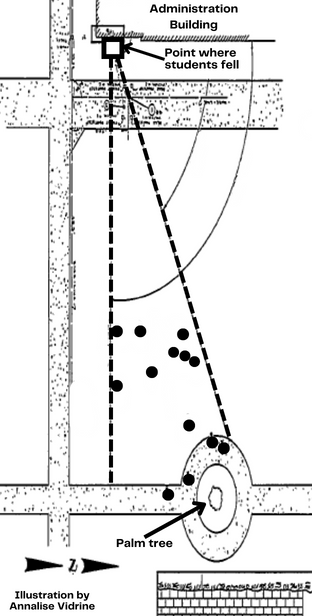

That accounted for 20 of the 27 pellets streaming from one buckshot shell, and FBI test-firings provided a range of possible shooting angles that all led to a cluster of deputies in front of or to one side of the tree. The deputies were there to disperse at least 200 students who had gathered after the arrests of campus protest leaders.

Gov. Edwin Edwards conferred with East Baton Rouge Parish Sheriff Al Amiss (first man on Edwards’ left with visor lifted) and other law-enforcement officials on the Southern campus after the shooting. Courtesy of Louisiana State Police

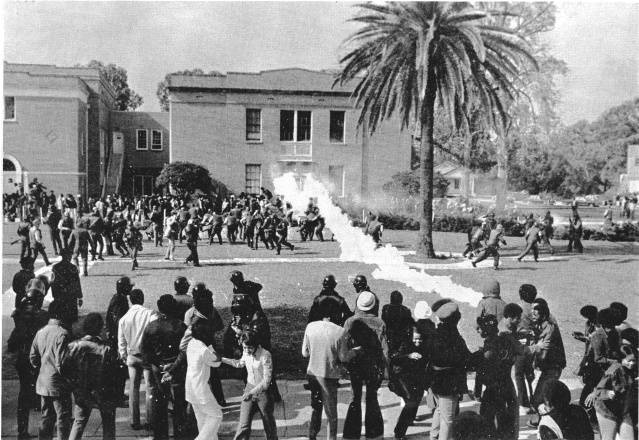

FBI agents collected more than 1,000 feet of film from TV news stations and nearly 70 photos from the State Police. They began analyzing them frame by frame, watching as Smith and Brown fell and noting where deputies were in the moments before and after the shooting.

Nearly 2,700 pages of FBI files obtained by the LSU Cold Case Project indicate that as more agents poured into town, they fanned out in pairs over three weeks to conduct 750 interviews and re-interviews, including several hundred with Southern students and officials, 47 with State Police officers and 91 with sheriff’s deputies.

Two dozen deputies had carried shotguns, the files say, but only nine were near the palm tree. As the FBI intensified its focus on those nine, it reenacted the shooting, with two agents standing where Smith and Brown last stood and others placed where deputies appeared in photos and films.

A land-surveying firm plotted the distance – 40 to 50 feet – between the students and deputies. It also marked some deputies’ locations within a triangle from which ballistics experts believed the shot had come.

This FBI diagram details the angle from which the fatal shot originated. The black circles represent where deputies were standing when the shot was fired.

But there were still big problems: All of the deputies denied firing the fatal shot or knowing who did. No image showed the exact moment it was fired. And no witness could definitively identify the shooter.

A couple of tips had come from Southern students, and the few Black deputies shared the chatter they were hearing. But nothing had checked out so far.

Few of the several hundred people there that day saw clearly what had happened. Tear gas filled the air. Many students were either fleeing or hunkering down in the building. And the event itself happened so quickly.

Even some deputies, who were wearing helmets with visors, had trouble identifying themselves in the photos. And two commissions that were investigating the shooting – one created by the governor, the other by civil rights leaders – also had come up with no clear leads.

So the FBI turned to an investigative tool that remains controversial today, asking each of the nine deputies who had held shotguns near the tree to take polygraphs, or lie-detector tests.

The tests measure a person’s physiological response in answering questions, and they are not always reliable or allowed as evidence in court. A guilty person who stays calm may pass the test. Someone who is innocent but nervous might fail.

“It was just a tool,” said Ed Walker, an FBI agent from New York who was sent to investigate the Southern shooting. “But if somebody flunked a polygraph badly – and the examiner is experienced and tells you – you can be pretty sure the guy is lying.”

There was another option: Compel the deputies to testify before a grand jury. Ossie Brown, who had just been elected district attorney for East Baton Rouge Parish, had promised to bring the case before a state grand jury.

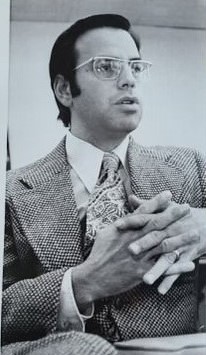

And if Brown did not get anywhere, federal prosecutors were willing to empanel their own grand jury, Stanley Pottinger, then the assistant U.S. attorney general for civil rights, recalled in a recent interview.

Such a move, he said, would “be a last ditch in a sense, the last string on the bow.”

This photo shows the 1973 grand jury with East Baton Rouge District Attorney Ossie Brown (top row, center). Juror Billy Badeaux is standing next to Brown and is fourth in from the right. Courtesy of Billy Badeaux

Stress and a mental breakdown

By mid-December 1972, four of the nine deputies had passed polygraphs, saying they did not fire the fatal shot or know who did. Five others refused to take tests, and memos by FBI agents and Justice Department lawyers provide an inside look at the efforts to analyze their actions and persuade them to talk.

Gary Bruce Wall, a deputy and jailor, who stood 6 feet, 5 inches and weighed 250 pounds, was the first of the five to become the focus of investigators – and he had himself to blame, the memos show.

In his first FBI interview, Wall said he was on one side of the palm tree when a tear gas canister landed near him. He tried to scoop it up, but it exploded, he said, knocking him to his knees. He said he retreated, taking cover behind Big Bertha, the bright blue armored vehicle parked in the street, and never fired his shotgun.

Agents easily spotted Wall in the photos and film: He had a shotgun with a special attachment for skeet shooting. They also could see that he had never made any of the movements he described.

An FBI agent confronted Wall, saying that if he was wrong about reaching for the canister and taking cover, maybe he had fired his weapon without realizing it, too.

Wall also may have faced another issue. Mike Barnett, another deputy, said in a recent interview that he told the FBI he had heard a shotgun blast that was louder than the tear gas ones coming from behind him around the time of the fatal shot.

Barnett did not see the shooter. But when the FBI showed him film, he said he pointed to a prison guard who seemed to be firing a shotgun with a special attachment, though he did not know the deputy’s name.

When agents asked Wall to take a polygraph, he stalled and hired a lawyer who accused them of “zeroing in” on his client.

Meanwhile, Lt. Robert “Bobby” Carr, another deputy who declined to take a polygraph, also placed himself in investigators’ sights, FBI files show.

Carr had been with the sheriff’s office for nearly a decade and had led a squad of deputies near the palm tree.

In his first interviews, Carr told the FBI that he had fired two tear gas shells toward the students. He also acknowledged that after the first canister exploded, he ordered his men to “lock and load,” even though only higher officials were supposed to issue such an order.

What agents did not know was he had been telling top sheriff’s officials since early December that he might have fired a third shot. His worry festered and, on Dec. 19, Carr told his bosses that he needed to change his story.

The next day, Sheriff Al Amiss and two other top officials met with Carr at his home. According to the FBI files, Carr told them he now believed he had fired three shots at Southern and that the third might have been buckshot.

Amiss immediately told federal officials about Carr’s “pangs of remorse,” the memos show. Carr hired a lawyer, who gave the FBI a written statement on Dec. 22 saying Carr probably fired three shots but that all three were tear gas.

And as agents continued to review the images, they concluded that neither Wall nor Carr, if firing from where they had stood, could likely have hit the students.

Over the next few months, both Wall and Carr left the department. Wall moved to Texas and died in 2003.

His widow, Pamela Wall, said he did not talk much about what happened at Southern, but it “bothered him a lot, it did. He just always felt it wasn’t right.”

In recent interviews, Carr said he had a mental breakdown after the shooting and was hospitalized. Investigators thought he blamed himself for the students’ deaths, but Carr said the stress of helping the agents pushed him over the edge.

“It was just a combination of everything that was taking place,” Carr said. “It was the hours we put in, trying to think over all of what took place, and trying to figure out who was there.”

As tear gas filled the area in front of the Southern administration building, many sheriff’s deputies fell back while others held positions roughly in front of a palm tree. Courtesy of SU Archives

Saying no to polygraphs

Three others who declined to take polygraphs were among the deputies in the area from which the shot came, according to several FBI and Justice Department memos.

All three – Melvin Story, Paul Potts and Wayne Cambre – gave the FBI accounts of their actions. But each responded differently in declining the polygraphs.

Story, a Navy veteran who had fought at Iwo Jima and Okinawa, said tear gas had entered his mask and that he did not remember who was standing next to him and never fired his shotgun. He politely declined the polygraph, one memo said, “with little or no comment.”

Potts, a former Army Ranger and a member of the sheriff’s new tactical team, told agents he put on his mask when he saw tear gas and did not retreat. He said he held his shotgun, barrel pointing up, and never fired.

Potts said he knew he would pass a polygraph but did not want to help narrow the field of suspects out of loyalty to the group. A fellow deputy probably “made a mistake,” he said, and if that deputy was convicted, “the whole group should be convicted.”

Cambre, a Vietnam combat veteran, told the FBI he had removed the live ammunition from his shotgun before going to campus. During the encounter, he said, he dropped to his hands and knees to avoid getting hit by something students had thrown and then got up on one knee. According to an FBI memo, he said he then fired a tear gas shell into bushes behind the crowd of students.

Cambre also told the FBI he saw Smith and Brown fall but did not realize they had been shot. After retreating from the gas, he said, he fired a second tear gas shell to disperse students gathering behind the deputies.

But when agents asked him on Dec. 12, 1972, if he would take a polygraph, Cambre became “extremely angry, hostile, and obstinate,” according to FBI memos.

Referring to his work as a deputy on other cases, Cambre said: “If I can get up on the stand and testify in court that results in a conviction, I certainly can tell anyone that I did not shoot the two students, and this should be enough.”

He also said the FBI “has now stopped investigating and started harassing,” the memos said.

Both Story and Potts have died. Cambre reiterated in a recent interview that he did not shoot the students and acknowledged that he was angry at the agents.

“I have no respect for the Yankee FBI agents,” he said.

He added that earlier in 1972, a fellow deputy who was a close friend had been killed in a shootout with Black Muslims. He said he asked the FBI agents why they were not as aggressive in investigating that shooting.

“They laughed at me,” he said.

Still just ‘educated guesswork’

By early 1973, the FBI had gathered as much evidence as it could. But it was circumstantial.

Jeffrey R. Whieldon, a prosecutor in the Justice Department’s criminal division in Washington, noted there was “no specific information” that identified the shooter. Even with the “careful analysis” of the images and the likely angle of the shot, he wrote, the names and locations of some of the nine deputies who had shotguns near the tree remained “merely a matter of educated guesswork.”

He also saw other hurdles to building a case: What if the deputy who fired the shot had made a mistake – forgetting whether live or tear gas shells were in his gun – and had no intent to shoot the students?

And what if he did not realize amid the chaos that he had fired the shot? In that case, Whieldon wrote, he also might be able to pass a polygraph saying he did not.

With Justice Department approval, the FBI shared its files with Ossie Brown, the district attorney in Baton Rouge, who was about to start calling deputies before a state grand jury.

If new evidence emerged, the state could seek the most appropriate charge, from murder or negligent homicide on down to assault with a deadly weapon. The federal government could only charge violations of the victims’ civil rights.

The state grand jury convened that March and met almost daily for four months to consider the Southern shooting and other cases. Brown’s team brought in 67 witnesses, including forensics experts, deputies and state troopers.

“They said they narrowed it down to a line of deputies,” one of the grand jurors, Billy Badeaux, recalled. “When they brought them up to testify, they said these are the six guys that were in that line where we think the shots came from.”

Fifty years later, he remembers feeling that some of the deputies were covering for each other. “One of them knew what the other was gonna say, and they all said the same thing,” Badeaux said.

The state grand jury wrapped up on July 28, 1973, without identifying the shooter.

A dramatic final witness

At that point, the FBI was ready to close the case. But Whieldon, the criminal prosecutor, argued in September 1972 that given the public importance of the case, the Justice Department had a moral obligation to convene a federal grand jury

“Its sole purpose would be to see if someone will ‘crack,’” Whieldon wrote.

Stanley Pottinger made key decisions in the Southern investigation in 1972 as the assistant U.S. attorney general for civil rights. Courtesy of Stanley Pottinger

Pottinger, the assistant attorney general for civil rights, agreed and told the FBI to check if Story, Potts and Cambre would take polygraphs. All three declined again. So Justice officials began planning how, as one memo put it, to get the “secret few” deputies to talk.

Steve Mayo, then a young assistant U.S. attorney in Baton Rouge, recalled how he and Whieldon pushed together tables in the office library in the spring of 1974, laying out blown-up photos showing the line of deputies.

“He and I were trying to figure out together which gun fired the deadly shot,” Mayo said.

And in a memo on May 8, prosecutors said they were willing to offer immunity from prosecution to any of eight deputies who could provide information that would “significantly aid” the grand jury.

The grand jury met in Baton Rouge from May 20 to May 28. Jurors heard from 35 witnesses, including Story, Potts and Cambre.

All three were sworn in, and each of them denied firing the fatal shot or knowing who did, Justice memos say. But for the first time, each of the three also said he would consider taking a polygraph, the memos say.

Cambre said in the recent interview that he remembers prosecutors trying to pit the deputies against each other.

“They treated us like crap,” Cambre, now 75, said. “They accused us, pointed fingers, saying, ‘This deputy said that about you, and that deputy said this about you, and you said this about that deputy.’ And I just told them ‘I don’t give a damn what somebody else said.’”

Asked how he thought the shooting could have happened, Cambre said in the interview that he did not know but that he presumed it was “probably an accident.”

About three weeks after the grand jury met, Story and Cambre again declined to take lie-detector tests. But Potts – who had repeatedly refused out of loyalty to fellow deputies – agreed to go ahead.

According to FBI memos, Potts said during the exam that he had looked to his right through the tear gas at Southern and seen a deputy on one knee firing some type of shot toward the students in front of the administration building.

Potts named the deputy, but the name is blacked out in the files released publicly. Potts’ description resembled Cambre’s account that he was on one knee when he fired his first tear gas shot into bushes by the building.

If Potts was referring to Cambre, he also supported Cambre’s account that he only had tear gas shells in his shotgun.

Potts described an exchange between himself and the other deputy as they retreated to the street behind the palm tree.

“What are you shooting?” Potts said he asked.

“Tear gas,” the other deputy said.

Potts said he watched as the deputy ejected two unused shells from his gun, and they both appeared to be tear gas.

When the polygraph examiner asked Potts if he had fired buckshot, he answered “no.” The examiner then named a number of other deputies – one by one – and asked if, to Potts’ knowledge, each had fired the fatal shot. Potts’ response to each name: “No.”

Potts passed the test, and with that, the investigation was effectively over.

This series is supported by the Data-Driven Reporting Project. Nearly 2,700 pages of FBI documents and Department of Justice reports are available here.