‘Shot heard ’round the pitch’ lands player at NSU

October 15, 2013

Military museum’s $1.35M construction begins

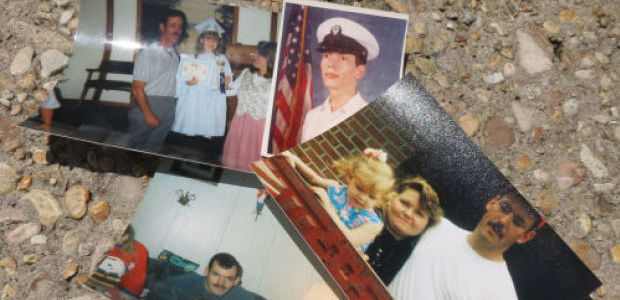

October 15, 2013They are the personal effects of a hero.

A St. Michael medallion on a chain, spotted with dried blood.

A knife.

A wallet.

Last week, nine months after Sgt. Rick Riggenbach was slain on a dusty St. Mary Parish road, they were turned over to his widow by Louisiana State Police investigators.

The return was painful, Bonnie Riggenbach acknowledges, but not as painful as a continued dearth of answers to questions about what happened on Flat Town Road, why law enforcement officers who should have backed her husband up allegedly fled the scene while bullets still flew, leaving him to die alone, and why prosecutors won’t let her see video of what occurred.

Bonnie Riggenbach is picking up allies who support her quest for answers, who agree that a fitting memorial to her husband – and other Louisiana law enforcement officers killed in the line of duty – is establishing a protocol of family advocacy for those they leave behind.

State Sen. Bret Allain, R-Franklin, is among a small group of lawmakers looking to see whether a legislative approach can help the process along, although such research is in the earliest stages.

“The idea should be studied and has some merit,” he said.

State Rep. Sam Jones, R-Franklin, a former St. Mary Parish deputy himself, agrees that whatever can help further comfort families should be explored. But he is not yet certain either whether the Legislature is the route for a solution.

ENOUGH TO DEAL WITH

Bonnie Riggenbach and other line-of-duty death survivors say that interface with the criminal justice system can be tough for law enforcement families. In some cases, angered and hurt parents or spouses can unknowingly poison their own communication with agencies that have essential information. In other cases, officials involved in prosecuting the people responsible for the death – although well meaning – may not only speak words that are not comforting, but which can be downright insulting to survivors.

“I think the victims shouldn’t have to negotiate with lawyers,” Bonnie Riggenbach said. “We are not emotionally prepared for that. I know I wasn’t. I wasn’t prepared to argue with them, to have disagreements with them. It is enough to just deal with my husband’s death. I shouldn’t have to deal with all this other stuff. I didn’t know what I was doing and I still don’t. If we had an advocate to talk to us and tell us what we can and cannot do with certain things it would definitely help.”

For her, mystery still shrouds details of the incident that claimed Rick Riggenbach’s life.

Information from some law enforcement officers and, more recently, details from witnesses, have resulted in disturbing questions that officials have not given direct answers to.

Chitimacha Tribal Police Sgt. Riggenbach, 52, was killed Jan. 26 when he responded to a report of a man with a gasoline can and a shotgun walking on Flat Town Road, where a trailer had just burst into flames.

Already shot – and later found inside the trailer – was Eddie Lyons, 78. The man with the gun and the gas can was Wilbert Thibodeaux, 48, a transient known by neighbors to have mental health issues and whom they had observed acting and speaking in a bizarre manner for several months.

The site was not on the reservation Riggenbach, a former St. Mary Parish deputy, normally patrolled. But it was not unusual for him and other Chitimacha officers to provide backup in the rural, isolated community.

St. Mary deputies arrived and – along with Riggenbach – engaged in a gunfight with Thibodeaux. Riggenbach was struck. Deputy Jason Javier was shot in the leg. Deputy Jason Strickland was also shot. The wounded pair withdrew, leaving Riggenbach to fend for himself. According to information received by Bonnie Riggenbach, other deputies were also at the scene but did not engage in the gunfight. Rick Riggenbach, who had been laying on the road alone bleeding, died in the arms of his department’s chief, Blaise Smith.

Thibodeaux was later arrested and faces two counts of capital murder and other charges.

I JUST WANT TO KNOW

For Bonnie Riggenbach, the account leaves open huge holes, including the possibility that at least one of the deputies at the scene had deserted her husband. Yet Sheriff Mark Hebert never publicly addressed that issue, and Bonnie Riggenbach’s demand for answers led to a breakdown in their relationship.

District Attorney Phil Haney has refused to allow Bonnie Riggenbach to view video from a patrol car and from the casino.

Law enforcement families in other parts of the country, advised of her spurned request, have maintained that in their jurisdictions there would be little trouble for a survivor to view such video.

Haney remains steadfast.

An advocate, Bonnie Riggenbach said, could have succeeded where she failed, and enabled viewing of the video, adding to her ability to cope with the tragedy, in her opinion.

While some law enforcement officers have questioned whether viewing video of the brutally murdered Rick Riggenbach would bring any closure or understanding at all, the widow says it is for her to decide what may help or not help.

“I have been dismissed and treated like a child,” Bonnie Riggenbach has said. “I just want to know what happened to my husband.”

She has spoken with Dorothy Tardy, mother of New Orleans police officer Christopher Russell, who was killed Aug. 4, 2002.

COULDN’T BE MORE SHAMEFUL

Russell had responded to an armed robbery call at a bar on the 1800 block of North Roman Street. As he arrived, three suspects were running from the bar and opened fire on the officers before they even exited their patrol car, striking Russell in the head.

One of the suspects was apprehended a short time later and charged with murder, attempted murder, and 16 counts of armed robbery. He was sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole on July 27, 2004. The three remaining suspects were apprehended within two days. Russell left behind an infant and a pregnant wife.

The trials for the suspects took years, and his mother said she ran into numerous problems while dealing with prosecutors and attempting to get information. New Orleans police officers offered some support, as did relatives of other slain officers. Told of Bonnie Riggenbach’s issues, Tardy said an advocate would definitely have helped.

“The actions of the DA and the sheriff couldn’t be more shameful,” Tardy said of Bonnie Riggenbach’s difficulties. “They are concerned with politics, ambition for what they feel they have in their future. I see that as their direction. I had an agency, the NOPD, that was really supportive and this woman is getting nothing.”

How does Tardy envision the role of a victim advocate specially trained to aid law enforcement families who lose an officer in the line of duty?

“I guess it would have to be statewide, independent of any prosecutor or the agency. When you run into this kind of horror story a victim advocate who would be loyal to either the sheriff or the district attorney could be a problem.”

NO ONE THERE

Allain and Jones are both willing to see what can be done, although there are practical issues – ranging from funding to jurisdiction – that could stand in the way of how an advocacy program can be developed legislatively.

Jones suggested that the Fraternal Order of Police might be of help. The national organization has a Louisiana chapter that is well networked with some law enforcement agencies.

“We would be willing to sit down with legislators and the families to see what could be developed,” said Louisiana FOP President Darrel Basco. We would want to be a part of those discussions.”

An organization called COPS – Concerns of Police Survivors – already provides some help to victim families. Tardy is a member and spends a lot of time attending trials and hearings with other survivors of line-of-duty deaths. Basco said that group could also contribute to a solution for law enforcement families.

Whatever direction the discussion takes, Tardy and other survivors say help can’t come too soon. She maintains that men and women who lose their lives protecting society deserve to have their loved ones taken care of emotionally within the justice system.

“For law enforcement families it is different as far as a death goes,” she said. “They protect us. They are the ones who stand between us and the criminals who want to do us harm and if we cant stand behind their families, what does it say about our society? Do we tell people that we abandoned their families? If we don’t stand with the families of our heroes, then what are we?”

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this story referred to Sgt. Rick Riggenbach’s wife as Mary Riggenbach. Her first name is Bonnie.

Chitimacha Tribal Police Sgt. Rick Riggenback, 52, was killed Jan. 26. Today, his survivors still are left wondering about the circumstances surrounding his shooting.