Olga Rieth

March 28, 2017

Forum for local Senate seat set for Friday

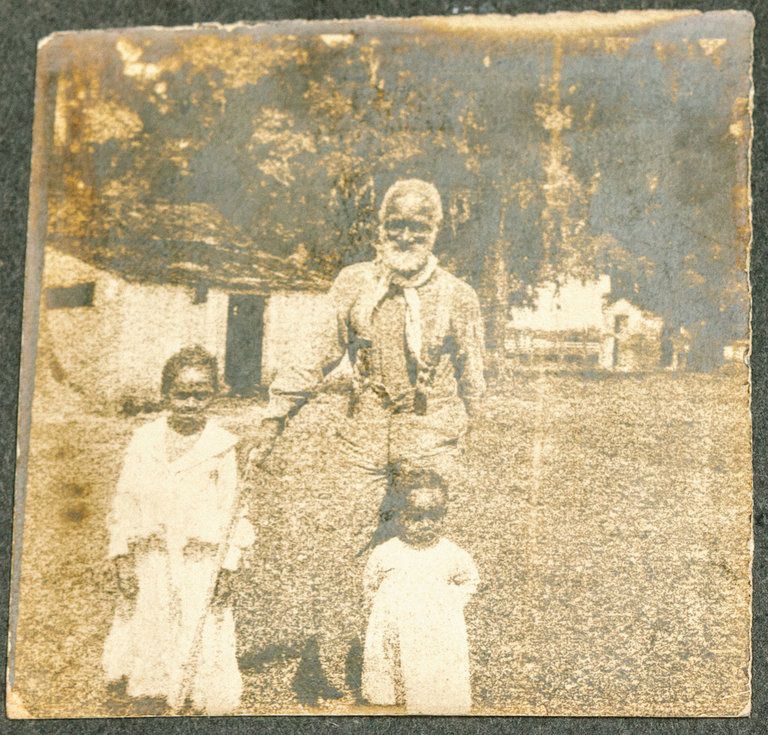

March 28, 2017In the coolness of his small wood-framed house in Chauvin, Earl Campbell gazed at an image of the ancestor he didn’t know existed until just a month ago.

“That’s him right there,” said the 94-year-old World War II veteran, as he spoke with pride of how thoroughly one of his daughters had explored the family tree, and of his amazement at the technology that allows such wonders.

He acknowledged – though appeared less impressed by – the unique place the photo of his great-great-grandfather has, in a history whose context is far greater than any one family’s genealogy.

The man in the photo is Frank Campbell, who was 19-years-old in 1838, when Jesuit priests in Maryland sold him along with 271 other slaves they owned to planters in Louisiana, in order to save the school they ran, which would later become Georgetown University. Purchased by a Terrebonne Parish sugar planter, Mr. Campbell lived to see freedom after the Civil War and continued plantation work in the employ of Robert Ruffin Barrow. He now rests with other family members within the New Mt. Zion Church cemetery in Houma.

The photo, taken in the early 1900s somewhere on Roberta Grove Plantation, has caused a great stir as Georgetown officials continue their attempts to make right the wrongs of the university’s slaveholding founders. Its link to Georgetown’s history and a special chapter of the African diaspora was made by the interim director of the Ellender Memorial Library at Nicholls State University, Clifton Theriot.

“I think the most exciting thing about the discovery is sharing the photos with the descendants,” said Theriot, who was reading a newspaper story about the Georgetown project and saw the name of Frank Campbell. Something about that name was familiar, and Theriot started checking the expansive archive at Nicholls.

In a photo album that had belonged to the Barrow family were three pictures of Frank Campbell.

“The reason I always remembered the photos was because of the captions,” Theriot said.

In pencil on one of the photos was written the mis-spelled name “Frank Cambell” and a notation that he was a servant of the family who was a teenager “when the stars fell in 1832.”

The night “when the stars fell” is a reference to a particularly memorable incarnation of the Leonid meteor shower on March 12-13, 1833, that was particularly active. More than 30 meteors per second fell through the skies. In some quarters the display caused panic, interpreted as an apocalyptic portent. The unusual occurrence was a common time-marker in the 19th century and even after.

EVIL HISTORY

Earl Campbell was told of his connection to history by his daughter, Earlene Campbell-Coleman, who is the family historian and lives in Charlotte, NC. She and her sister, Nancy, who lives in Wisconsin, traveled to Louisiana to view the original photographs firsthand, and they visited Earl, sharing the news with him.

“He couldn’t believe it,” Earlene said. “The last time I was down there everyone knew I was doing family history on the Campbells. But I couldn’t find out how they got to Louisiana.”

The answer lies in the history of Georgetown University.

Founded in 1789 as Georgetown College, the school from its beginnings relied on income from tobacco plantations worked by enslaved people. Jesuit priests gained control of its board. The plantations continued to operate. But in the 1830s two prominent Jesuits, William McSherry and Thomas Mulledy, saw financial trouble ahead and started selling off small groups of slaves. In 1838 Father Mulledy was given the task of selling off the remaining slaves.

Terrebonne Parish planter Jesse Batey and his business associate, U.S. Rep. Henry Johnson, a former governor of Louisiana and uncle of a Georgetown student , were willing buyers.

More than 50 of the 272 slaves sold off in 1838 to pay mounting debt ended up in Terrebonne Parish, and later sold to other plantations including some in Lafourche. The remainder of the 272 went to plantations in Iberville and Ascension parishes. The 1838 transactions brought Georgetown $3 million and are credited with saving the school.

“This original evil that shaped the early years of the Republic was present here,” Georgetown president Georgetown University President John DeGioia said last year. “We have been able to hide from this truth, bury this truth, ignore and deny this truth.”

In 2015 the university convened its Working Group on Slavery, Memory, and Reconciliation “to explore this history, to engage the community in dialogue, and to outline a set of recommendations to guide future efforts.”

The project has thus far identified more than 4,000 descendants, both living and dead, of slaves held by the Georgetown priests.

Baton Rouge researcher Judy Riffel has pored through archives in Terrebonne and Lafourche, initiating contact with potential descendants. Their purpose is to identify as completely as possible the human connections from the past to the present. Ancestry.com is donating DNA kits to aid in the process.

“I learned that the Terrebonne group were the first group to arrive anywhere in Louisiana from Maryland,” said Riffel. “They were gathered up from two plantations and sent on ships, it was fifty some-odd in the Terrebonne group that they put on a boat and sent in June of 1938 and they arrived in New Orleans in July. A document in the courthouse lists everyone who was on the boat. Some missed the boat and one was sent a few months later.”

Riffel said that after arriving in New Orleans, the slaves were sent to Terrebonne on flatboats.

The Batey plantation, where many were sent, was in a place referred to as “Bateyville,” now known as Gray, just south of Schriever and north of Houma. Batey, whose name is sometimes spelled Beattie, was a doctor of dentistry, according to Browning, whose holdings were expansive.

BEGGING FOR ROSARIES

Jesuit officials in Rome frowned on the idea of a mass slave sale, instead favoring their liberation. Mulledy demurred, and Rome put conditions on the sale. Families would not be separated. The slaves, who had been baptized and practiced Catholicism, would have their religious needs met and accommodated.

Historical records and accounts based on them strongly indicate that not everyone in the Jesuit community of Maryland was so sure.

The Rev. Thomas Lilly wrote in a letter to superiors that slaves from St. Thomas Manor were “dragged off by force to the ship and led off to Louisiana. The danger to their souls is certain.” Another Jesuit, Peter Havermans, wrote of the slaves’ “heroic courage and Christian resignation.”

Havermans related that an elder female slave had begged him to know what she had done to deserve being wrenched away from Maryland.

“All the others came to me seeking rosaries,” Havermans wrote.

The ship that bore the Georgetown slaves from Maryland was the schooner Uncas, a 66-foot sailing vessel engaged in coastwise trade. At a New Orleans dock, they were transferred to the flatboat that completed the trip to Terrebonne, and the labor-intensive tasks of planting, cutting, hauling and scrapping cane. Georgetown officials acknowledge that the request for the Catholic faith to be kept was not honored, nor the requirement that families be kept together.

Frank Campbell’s photo appears in a book written by Dr. Christopher Cenac, “Hardscrabble to Hallelujah, Volume 1 Bayou Terrebonne: Legacies of Terrebonne Parish”(University Press of Mississippi, 2017.)

According to records compiled by the Memory Project, Frank Campbell was born around 1819 on one of the Maryland plantations. Unlike some of the other slaves who were sold by the priests, Frank was allowed to leave with his parents, Watt and Theresa Campbell. The Maryland plantation he was sold from was called Indigoes.

The value placed on Frank was $420 around the time of the Georgetown sale. He is valued at $1,150 in a Batey plantation inventory and was sold for $2,320 along with his wife and their child during a later sale, likely to the Barrows.

“GOOD ARCHIVIST”

Frank lived through the Civil War and as a free man bought land in Houma – possibly on what is now Samuel Street in Mechanicville – for $50.

It was after Clifton Theriot read about the Georgetown project and saw the names of known slaves that he recognized the Frank Campbell reference.

“That is so much the work of a good archivist, who really knows his material,” said Montegut consultant Laura Browning, who aided Riffel with some of the Terrebonne Parish work and is familiar with Theriot’s accomplishements, which include discovery of documents last year that shed new light on the mass killings of striking sugar cane workers in 1887 known as the Thibodaux Massacre.

When Theriot made the connection in December between the photo in his collection and the name in the Georgetown rolls, he notified Riffel. She contacted Richard Cellini, the Georgetown alumnus who is founder of the Memory Project, and the link was verified.

It was Cellini who contacted Earlene Campbell-Coleman at her Charlotte, NC home through e-mail.

“My feelings I have been trying to describe to people these past two weeks,” the retired nurse said. “They range from shock and disbelief to amazement, to tears. It is bittersweet.”

“It is so sweet because this information needs to be known and not forgotten and needs to be honored,” Earlene said. “It needs to be honored, this knowledge that these people survived atrocities. My great-great-great grandfather, who was being sent from the home he was used to, he was still born into slavery. Where were the rest of my family members? I don’t know Maybe in Lafourche or Ascension. They could have been on another plantation. I still am amazed.”

Earlene said she is appreciative of the work being done by the Memory Project. There will be a memorial breakfast next month that she shall attend. She is aware that Georgetown is offering legacy status to provable descendants of the university’s slaves.

“I feel they have done quite a bit so far, and they have to wrap their heads around this too,” she said. “But I am expecting more.”

“I hate to have to say this, but in the political climate we are in, there are many alternative facts circulating,” Earlene said. “In 2017 acknowledgement is therefore a big thing, acknowledgement from the general population of white Americans that these things in fact happened, and that hundreds of years later this is still affecting the descendants, physically, emotionally and spiritually.”