Player of the Week – Peyton Bonvillain

November 5, 2014

Elevated La. 1 project support continues

November 5, 2014A nationally-recognized environmental organization’s DNA tests of shrimp sold in restaurants and retail outlets reveals rampant misrepresentation of the seafood’s origin.

The study, done by the group Oceana, resulted in shrimp that only occurs in overseas aquaculture operations passing for “wild-caught” or “Gulf” shrimp. In one case a shrimp not even harvested for human consumption, but sold as an aquarium pet, was in the mix.

“The majority of restaurant menus surveyed did not provide the diner with any information on the type of shrimp, whether it was farmed, wild or its origin,” the study says. “Misrepresenting shrimp not only leaves consumers in the dark, but it also hurts honest fishermen who are trying to sell their products into the market. Instituting full-chain traceability and providing more information at the point of sale will benefit all stakeholders in the supply chain, from fishermen and seafood businesses to consumers. Traceability can also prevent illegally caught seafood from entering the marketplace and deter human rights violations around the world, while giving consumers the information they need to make fully informed, responsible seafood choices.”

Alleged misrepresentation was not limited to major markets like New York City, although they were included.

Mis-labeled shrimp was encountered in restaurants and groceries in New Orleans, Lafayette and other Gulf of Mexico region locales.

Local fishermen, processors and other domestic seafood industry voices say the group’s study confirms fraud they have long suspected, and sheds light on the importance to consumers of demanding to know where their seafood is from.

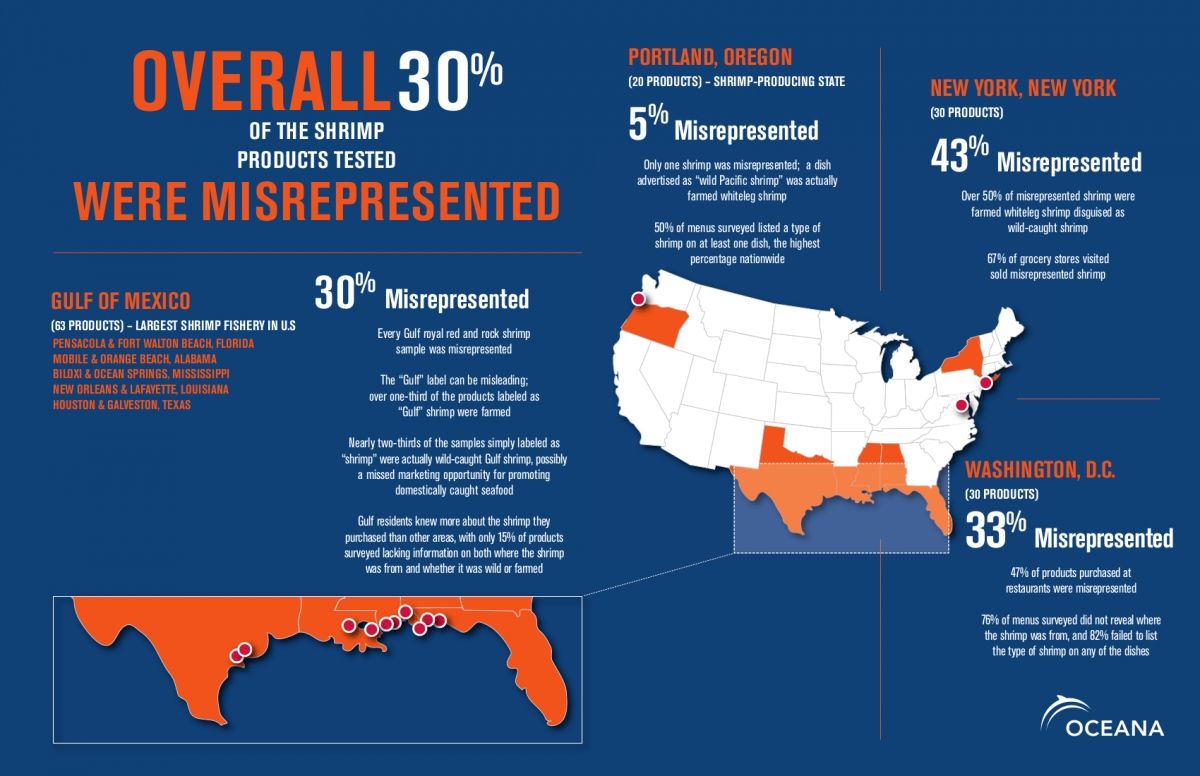

The rate of misrepresentation, Oceana states, was around 30 percent in some places.

“While we have not yet been able to evaluate the quality of the science in the report, on the face of it, we are appalled by the numbers,” said David Veal, director of the American Shrimp Processors Association. “It is in our best interest for all shrimp to be represented properly. We actively encourage consumers – whether they are individuals, chefs, restaurants or retail buyers – to question the origin of their shrimp.”

The Oceana report, released last week, states that 30 percent of 143 shrimp products tested from 111 vendors visited nationwide were misrepresented.

“Of the 70 restaurants visited, 31 percent sold misrepresented products, while 41 percent of the 41 grocery stores and markets visited sold misrepresented products,” the report states.

The most common substitutions, according to the report, were farmed white-leg shrimp sold as “wild” shrimp and “Gulf” shrimp. That species is only found on shrimp farms, which with rare exceptions do not exist in the US.

A total of 20 separate shrimp species were collected that have never been known to have been sold in the U.S., the report states.

Kim Warner, the marine scientist who directed the U.S. study, said in an interview with The Times that samples were sent to a Florida laboratory for the actual analysis.

“We spent about the first half of 2013 collecting samples,” she said. “They applied what we think are good technologies.”

The study – the first of its kind known to have been undertaken – relies on match-ups of DNA from shrimp to the species known to frequent a particular area of the globe.

Wild brown or white shrimp from Louisiana, Texas or Mexico, she explained, have a different DNA makeup than the white-leg shrimp common to aquaculture.

Likewise Mexican blue shrimp or tiger prawns would not be found in the Pacific northwest.

Warner said there is always the possibility of an “accidental” – a shrimp found somewhere in the wild that is not its usual haunt – but those instances are too rare, she contends, to have affected the quality of the data.

What Warner found disturbing – although intriguing – were the shrimp that did not fit known profiles for commercially viable species.

“Talk about not knowing what you are eating,” she quipped.

In addition to the one instance of an aquarium shrimp, there were several unidentifiable and previously unknown species.

The aquarium pet, a banded coral shrimp, was found in a bag of frozen imported shrimp, salad-sized.

The Oceana report states that the findings are relevant to consumers for several reasons.

Allegations of human trafficking associated with some Asian shrimp operations as well as destruction of mangroves and other environmental concerns motivate some consumers to desire only wild-caught shrimp.

From a sustainability perspective, some shrimp are considered more environmentally friendly by organizations such as the Monterey Bay Aquarium.

Their “Seafood Watch” warns environmentally-conscious consumers away from certain catches.

Ironically, due to the aquarium’s concerns about which jurisdictions enforce bycatch restrictions, some Louisiana wild-caught shrimp is red-flagged by Seafood Watch.

Some consumers are also concerned about antibiotics used in shrimp ponds from a health perspective.

Those are among the reasons Oceana and other interested organizations say the more information about where seafood comes from the better.

In Terrebonne, Lafourche and surrounding parishes fishermen and their advocates have raised consumer awareness to some degree, encouraging consumption of local shrimp in local restaurants and markets. Rouses, Cannata’s, Frank’s and other local retailers including small operations make a point of marketing local shrimp.

Consumers here have the option of buying directly from the boat.

But in New York, Washington, D.C., and other major markets, the study notes, consumer awareness is not so high, and neither is the motivation for stores or restaurants to supply information about shrimp origins.

Warner said Oceana has approached the Food and Drug Administration with an offer to share their data, including information on where misrepresented shrimp was purchased.

They will also share it with other governmental agencies upon request.

Warner would not share the information with The Times, however.

The study only identified the approximate origin of the shrimp, and was not an investigation of how it got onto the plate or in the package used for the study.

In some cases restaurants or retailers, Warner said, may have purchased shrimp without knowing they were misrepresented.

“I think it’s a good start,” said George Barisich, president of the Louisiana-based United Commercial Fishermen’s Association, whose membership includes local shrimpers, and who has long campaigned for tighter restrictions on imports, to keep their low prices from affecting harvesters here. “The price is falling again. There’s no price. So I have probably stopped fishing for this year.”

The full report may be viewed at www.oceana.org.