A page torn from history: Bayou area’s hidden past emerging from the shadows

July 15, 2015Are we a Christian nation or a nation where a lot of people are Christian?

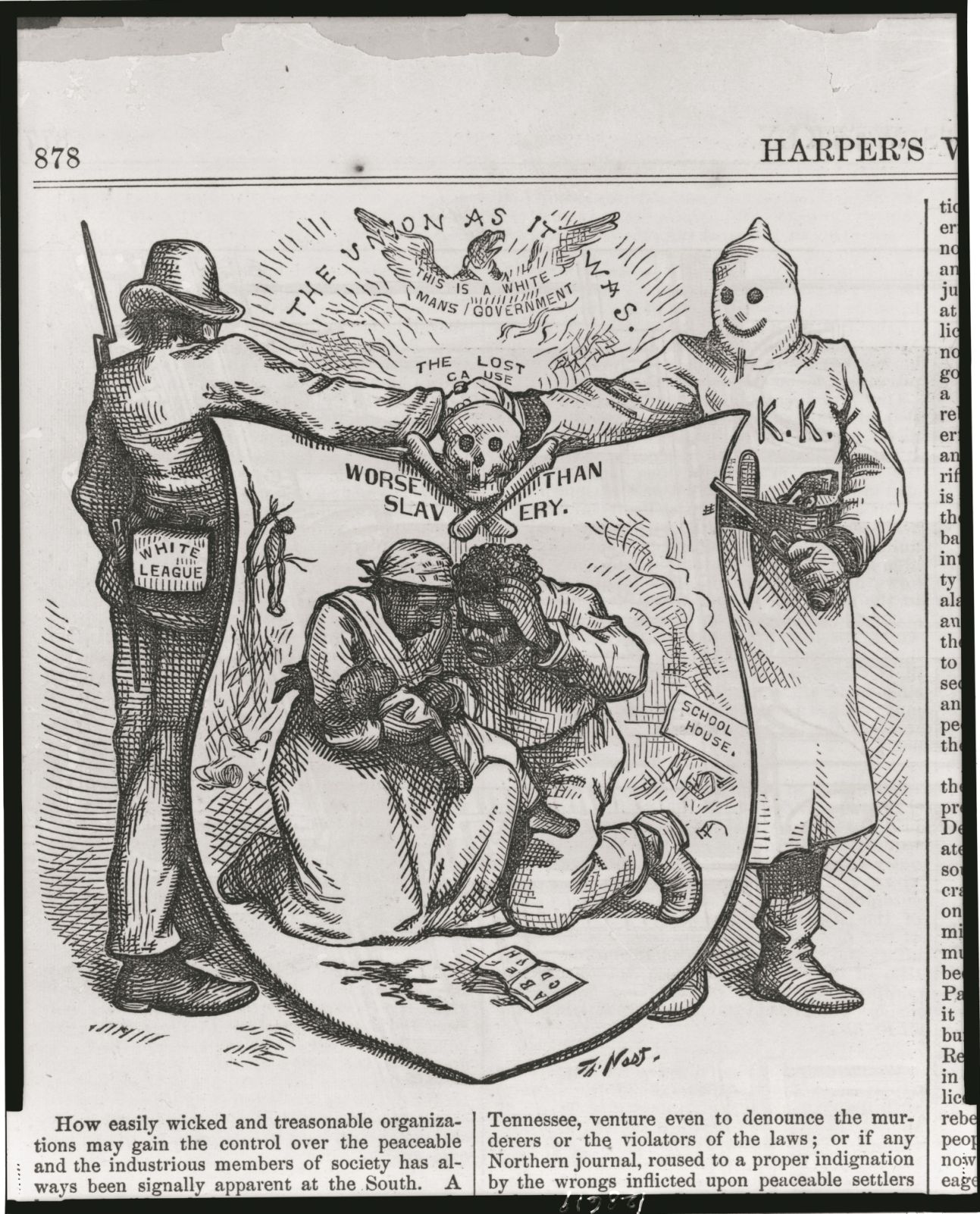

July 15, 2015A tumultuous combination of political strife and violence along with sometimes brutal displays of power by avowed white supremacists rocked Louisiana in the years that followed the Civil War.

As with many such conflagrations, historians point to economics as the seed that grew intolerance and the violence that came with it.

Already subject to the rule of federal troops, frustrated in their attempts to rejoin the union and eager to throw off the yoke of Reconstruction, planters and business leaders formed curious alliances that resulted in a confusing and volatile political climate.

The post-war years locally saw attempts to control elections by manipulation and intimidation of newly enfranchised black voters, although the region did not see the wholesale violence that visited northern parishes.

Terrebonne, Lafourche and Assumption, says Nicholls State University history professor Steve Michot, were among Louisiana’s hardest-hit after the war in economic terms.

“The impact was devastating,” Michot said. “Property loss in the three-parish region was about $30 million just in the matter of real property.”

The average value of land per acre, Michot maintains, fell from $38,000 in 1860 to $20,000 in 1870, five years after the end of the war. The region would not rebound to antebellum land values until about 1920. The war also resulted in loss of free labor for planters in the three parishes, who were deprived due to emancipation of slaves valued at about $30 million.

Emancipation meant that planters had to pay for the labor-intensive growth and harvest of their cane.

The political picture at war’s end was grim. Barely a year after its 1865 ending a riot broke out in New Orleans as local Democrats – primarily men of property and former power – attacked blacks who were parading outside of a Republican constitutional convention, with at least 38 deaths reported. The 1872 gubernatorial election saw the installation of Republican William Pitt Kellogg, with the blessing of President U.S. Grant, and New Orleans Democrats were not going to stand for it.

On April 13, 1873, more than 100 blacks were killed in Colfax, La., half of them, according to historical accounts, murdered after they surrendered to members of the pro-Democratic White League.

A little over a year later, on Sept. 14, 1874, about 5,000 members of the Crescent City White League – Democrats, many of whom were ex-confederates – overwhelmed an undermanned, mostly black metropolitan police force during the Battle of Liberty Place on and around Canal Street while forcibly attempting to install white supremacist rule over the state after overthrowing Kellogg. The arrival of federal troops ended their three-day siege.

The White League and the Knights of the White Camelia were among white supremacy groups that began to flourish. Among their members, according to Louisiana historian William Ivy Hair and other chroniclers, was a Thibodaux judge and planter named Taylor Beattie.

A black state militia unit in Thibodaux led by Raceland native Benjamin Lewis, whose drills in the middle of town, according to some letters, grated on the sensibilities of local planters, was disarmed.

The 1876 presidential election included violence and rumors, apparently discounted according to testimony in the Congressional Record, of a planned black insurrection in Thibodaux. Former Confederate general Francis T. Nicholls, a Democrat, was granted the claim to his win as part of an unwritten but historically documented compromise that included the removal of federal troops from Louisiana and the ascension of Republican presidential candidate Rutherford B. Hayes to the White House.

In 1879 Judge Beattie ran for governor as a Republican against Democrat Louis Wiltz, whose supporters were accused of massive intimidation of black voters into voting their ticket. Wiltz was the victor but his tenure did not last long. He died of tuberculosis in 1881 and was succeeded by Lt. Gov. Samuel McEnery of Monroe, a cotton planter.

It was McEnery who ordered state militia members to Thibodaux in response a strike by cane workers in 1887, setting the stage for the violence that would come.