Lafourche opts for government term limits

December 13, 2016Our View: Keep Polite

December 13, 2016Under pressure to cull contracts and expenses wherever feasible as Louisiana faces the specter of a massive budget deficit, officials at the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries plan to phase out a popular program for collection of data on speckled trout, redfish and other species.

The Louisiana Cooperative Marine Fish Tagging Program is a collaborative effort between the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries, the Coastal Conservation Association and associated universities, largely funded through match grants from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. More than a quarter million individual fish have been tagged through the program, which was initiated privately by the CCA in 1985 but later resulted in a state partnership.

The program utilizes sport fishers who have received kits with tags and training, who tag fish they catch and note information that includes date, place and size. Taggers can “follow” the fish they have tagged, and are also notified if one of their tagged and released fish is recaptured.

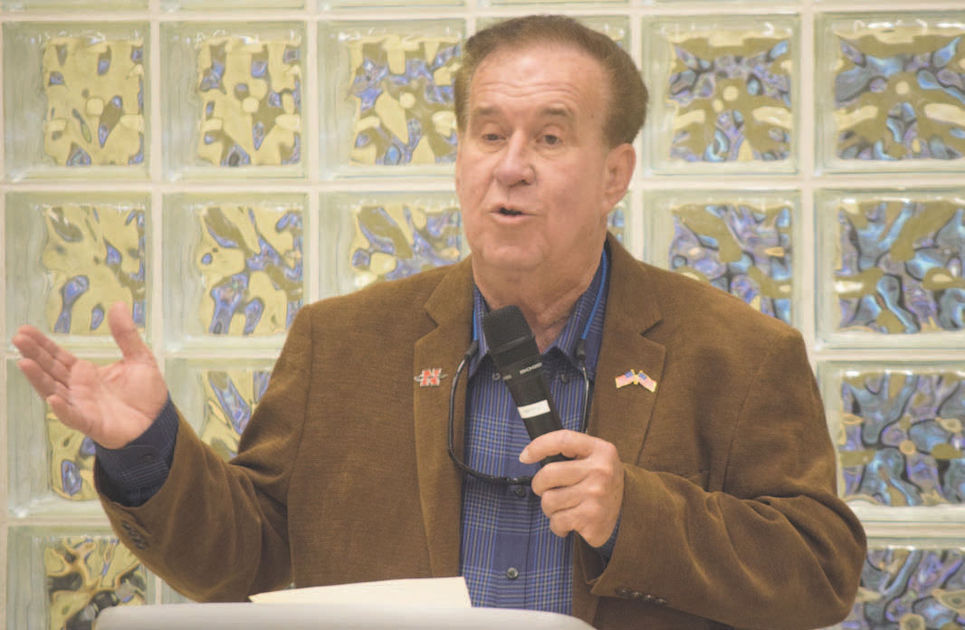

Wildlife and Fisheries Secretary Charlie Melancon said last week that while he recognizes the program’s popularity, the data it provides to the state is not essential for fisheries management.

“When I came in as secretary one of the first things we sat down and saw the state was facing deficit spending, and said we are going to start looking at what is a need and what is a want and those that are wants we are going to try to weed them out,” Melancon said. “We need to focus on our core mission, which is what the Constitution requires us to do.”

The Tag Louisiana program was lauded under the administration of Melancon’s predecessor, Robert Barham. But the $200,000 in annual contract payments was among an estimated $6 to $8 million that Melancon said was scrutinized by audits and investigations into how LDWF does business.

“The previous administration talked about the program and how good it was, and now Patrick Banks, of the fisheries division, what he is finding is that what was said was being derived from the tagging program wasn’t anything that gave us scientific data for managing the fisheries.”

Banks said the program is not being canceled outright, but its scope is being reduced.

“It is good outreach,” Banks said. “The angler loves to receive the information from a tagged fish and we are continuing to do that. We are not continuing to put more tags out there.”

CCA Louisiana Executive Director David Cresson discounts suggestions that the data is not valuable for fisheries management.

Fish weight, place of capture, the sort of bait used at time of capture, even the type of hook, all have value, Cresson said.

“We learn all sorts of things about movements and growth and what they are eating, there is an amazing amount of data that is provided through each tagged fish,” said Cresson, maintaining that the benefits of the program, as currently administered, transcend mere numbers. The tagging, for those who participate, adds an extra level of involvement in the fishery that teaches youngsters stewardship of marine resources.

“I have tagged fish, especially with my two young boys that love to fish, and it is something different for them,” Cresson said. “We understand that there are tough decisions, that the state is dealing with difficult budget decisions, tough decisions they have to make. But, in this particular case I don’t get it. There are federal funds that come from taxes on fishing tackle. It is not that these are general fund dollars so they are not going to be used to fund programs that are already existing.”

Officials at the agency, however, said that their budget structure allows for no general fund money, and that contracts and programs must be considered on a case-by-case basis.

“This program is not part of the core mission,” Melancon said. “This is a matter of the state has a fiscal problem and it is my responsibility to get this agency in ship-shape and take us as far as we can go before we get into a deficit situation. We just took a $4.2 million haircut and they are proposing a new $2.6 million haircut.”

Money the state spends on the program, Melancon said, comes out of its conservation program funds, and other priorities exist, including those that have survived the budget ax which are intertwined with CCA, such as the Rigs-to-Reefs program.

Melancon said the fiscal realities he must endure include a department that is down by 23 wildlife enforcement agents.

Threats to enforcement as well as the departments overall aquatic programs are still distinct potentials, Melancon said.

Banks stressed that the program will continue in terms of data being collected from fish already tagged, and that anglers with tagged fish should still be able to follow them.

“We are not getting out of the tagging world altogether,” Banks said.

Cresson said he and state officials are discussing how the program might continue.