Houma Police Officer named top cop in state

April 29, 2015

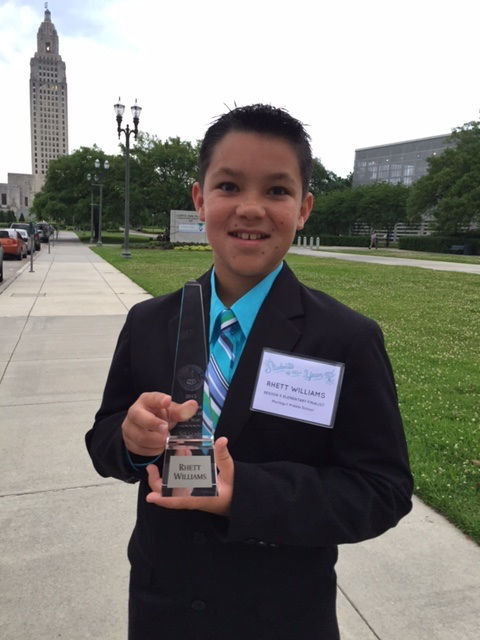

Montegut Middle student honored

April 29, 2015The doors are not yet open.

But when they are, Terrebonne Parish officials say they’re betting a new set of procedures and protocols will keep qualifying young offenders from being swallowed up by a hungry juvenile justice system long on punishment but short on lasting solutions, while also offering parents access to resources and services.

The concept is construction of a virtual village that can help parents provide what is needed for a child before he or she offends, and also to deal with juvenile offenders in a humane and productive manner.

“I see a very dedicated group of people, from the Parish President to the Youth Board, seeing our kids entering into the juvenile justice system that don’t really need to be,” said Kevin Champagne, director of the non-profit MacDonell Children’s Services, on whose bucolic grounds an intake center for a program called SPARC is near completion.

SPARC stands for Single Point Assessment Resource Center; it is modeled after programs already meeting with success in Lake Charles, Jefferson Parish and other communities that over the past few years have made major investments in diversion for youngsters who might otherwise end up in Louisiana’s oft-criticized juvenile justice meat-grinder.

Once renovations to the formerly vacant building on the MacDonell property are complete, it will in many cases be the first stop for children who get in trouble with the law, and hopefully a source of information and comfort for parents and other care-givers who want to aid children before they ever have a chance to get into trouble.

Its development marks what organizers say is an unprecedented partnership between law enforcement, prosecutors, social service providers and school officials to divert youngsters away from the criminal justice system when possible.

Terrebonne Parish has its own juvenile detention center, which will soon move from a location right next door to the parish jail to a new setting in the northern end of the parish.

SPARC is not intended to replace the detention center, which is still an important component of the local juvenile justice system, organizers said.

“Our detention center does have some proactive things going on there ,” said Brenda Johnson, chairwoman of the parish’s Children and Youth Services Planning Board, which will oversee SPARC operations. “Our biggest concern is that if they immediately go to detention you introduce them to that more serious criminal element and you erase the initial fear.”

For decades a get-tough approach seen in some cases as more stringent than that applied to minimally offending adults has been locally employed. A zero-tolerance policy in local schools resulted in arrests for simple schoolyard fights, or “fistic encounters” as the policy defined them.

The combined result was scene after scene of children who had been held in detention for as long as two to three days in some cases for minor offenses, bursting into tears as they were led shackled into a courtroom where parents or other caregivers awaited them.

Once the SPARC doors open police will bring children accused of relatively minor offenses there, and the assessments will determine what the next step should be.

Mental health care, counseling, dispute resolution or an appearance before a judge at a later date – but set not too far in the future – are among the options that could be applied.

But SPARC has another component that has little to do with the justice system and much to do with seeing to it that a child at risk for bad behavior or in need of special services can receive an intervention or a referral should a parent come asking for help.

The hope, said SPARC director Christopher Steward, is that in the long run parents will have “one stop shopping” options, while keeping kids far from places where they can meet children who can be bad influences.

The SPARC’s annual budget of $250,000 is for now provided directly from the Terrebonne Parish Consolidated Government. Parish President Michel Claudet has a been a strong booster of the program.

A Terrebonne Parish deputy will be on site during all hours the SPARC is open, for security and what other assistance may be required. The deputy, who has experience dealing with juvenile matters, is being provided by Sheriff Jerry Larpenter out of his own budget.

The program is only funded for two years; additional money could come from the parish if success can be documented.

Supporters say the streamlining of services for children will save money overall, as well as get children adjudicated into court rapidly, while the circumstances leading to their coming to official attention are still fresh.

“Our goal is if a kid who is charged with a misdemeanor delinquent offense our goal is that once they get to the SPARC that within 48 to 72 hours they are hooked up with a service,” said Johnson, explaining that after processing and evaluation a child will in most cases go home with a parent rather than into detention.

Assistant District Attorney Bernadette Pickett, who serves on the SPARC Advisory Board, said that a child may be ordered through SPARC to attend substance abuse classes or some other diversion. But that doesn’t eliminate consequences.

“If they don’t do this they are referred back to the District Attorney’s Office, so they are not getting away with anything,” Pickett said. “Our goal is to make them realize their consequences. But the consequences should not hurt them. If you go out and you steal a loaf of bread out of Rouses you are going to suffer the consequences for doing that. But hopefully we will give you the tools for you to know why that is a bad decision.”

Lengthy probation sentences for minor juvenile offenders have served, officials said, to criminalize children rather than keep them away from trouble. Under probation supervision a minor offense can land a child back into the system.

Keara Plaisance, an attorney who represents children in juvenile court and is also on the SPARC board, said relying on incarnation can take away innocence from children whose offense might be chalked up to their just being children.

“You want to save detention for felons,” she said. “This won’t close the detention center. There are kids who will need to be help for various reasons. But this stops kids who aren’t delinquent from learning to be delinquent. Also detention doesn’t seem to work as a punishment. Once the child goes into detention you have taken away the big stick. The fear of going to detention is gone.”

Det. Jerry Bergeron, a Sheriff’s Office juvenile officer, said he has seen the negative results of putting non-threatening offenders into juvenile detention.

“Little Johnny who has just made a goofy decision and has never been in trouble before is sitting there in detention with someone who is a serious offender,” Bergeron said. “Little Johnny gets out and the serious offender gets out and then they’re hanging out together.”

Providing services promptly removes the probation stigma and the potential of institutionalization, SPARC organizers said, and quick scheduling of court appearances will make the realities of consequence more vivid for youngsters.

Involvement of the school system, particularly from the referral standpoint, will be an key component.

“This will have a more proactive diagnostic aspect than what we can do,” said Assistant Superintendent of Schools Carole Davis, one of several officials who have toured similar sites in other communities. “It is a way to see what services can be afforded to the family and to students, what kind of support. What we had done in the past to be honest was zero tolerance on a first offense. That was the consequence. There was no element of saying this has happened, now let’s call in the family and see how we can provide support to this young person that can be proactive.”

Johnson said the SPARC can plug other systemic holes. Children diagnosed with autism, she acknowledged, have been criminalized rather than been diverted to helpful services. The result can have devastating effects on a child’s future.

“People in Terrebonne Parish are very leery about helping at-risk kids, I have never seen this community embrace underprivileged or at-risk kids,” Johnson said. Pastors and other clergy members have told her in her past work with Houma City Court ‘I don’t want those kind of kids in my church.’ But it is essential that we get the community to buy in to the SPARC and embrace it. We feel that this is the best way to get our community as a whole to support this.”

Statistics from juvenile court verify the theory that most children who are the subject of police contact have committed relatively minor offenses.

In 2014 1,283 cases came through Houma’s juvenile court. Of those 84 percent were status offenses – curfew violations, possession of tobacco or other crimes charged specifically because someone is a juvenile – or misdemeanors.

A total of 16 cases involved felonies.

Through a connection with officials in Jefferson Parish, which is working closely with the Annie E. Casey Foundation for Children and Families, Terrebonne will now have access to professionals who can come to the parish and provide help and guidance as the SPARC program progresses, board members said.

An up-to-date directory of services, Johnson said, is a key component of the SPARC, especially for parents who think children need guidance or a helping hand away from trouble that looms on the horizon.

Bergeron said many of the parish’s agencies have been familiar with services that can help families, but that there has been no central clearinghouse. The SPARC, he said, changes that.

“Now when I get a call from a mom at the Sheriff’s Office I can say ‘let me give you the number to the SPARC,’” Bergeron said. “Parents can go and speak to somebody that knows what they are talking about and knows what’s out there.”