Houma man’s body found in Intracoastal Waterway

May 27, 2021

Free drinks offered to Louisianans who receive COVID vaccine in ‘Shot for a Shot’ campaign in June

May 27, 2021After around six months since Terrebonne Parish Sheriff Tim Soignet first presented a plan for traffic enforcement cameras in school zones, the time finally arrived for the Terrebonne Parish Council to consider adopting legislation for the safety measure.

Wednesday’s proposed ordinance would have amended the Parish Code of Ordinances to allow for enforcement of traffic violations by automated means; however, the council decided to table the legislation after a heated discussion on its legality and intention.

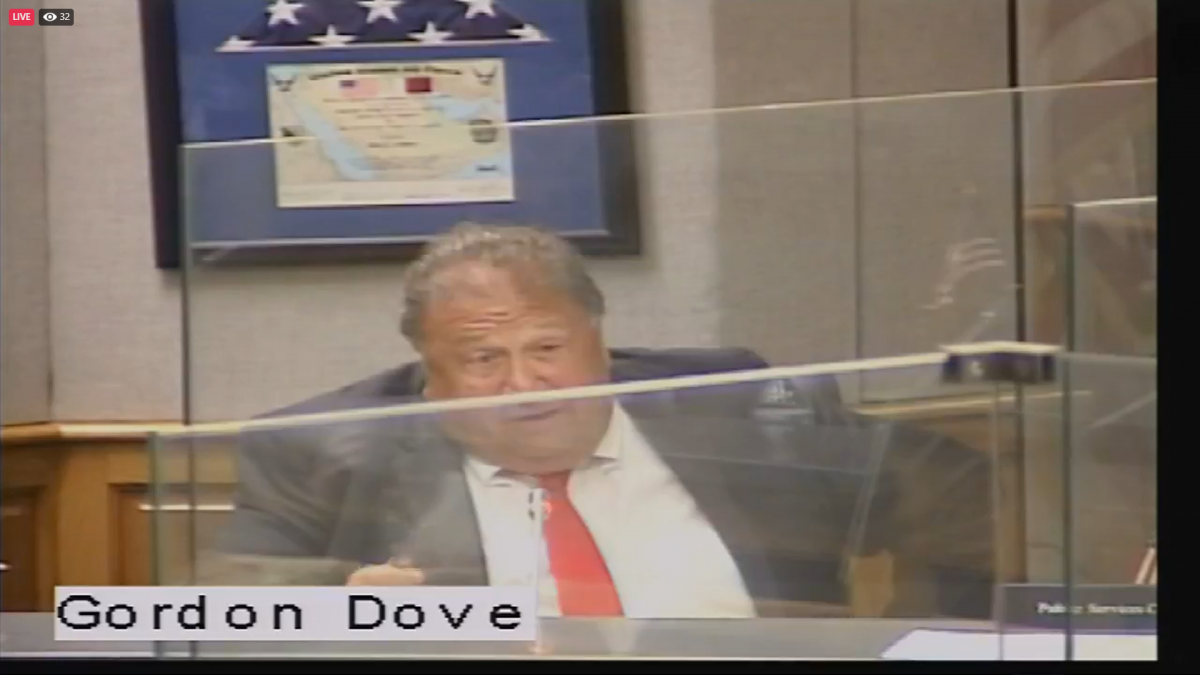

Terrebonne Parish President Gordon Dove, who referenced a $25 million lawsuit against the City of New Orleans regarding photo enforcement, argued that the ordinance as drafted is unconstitutional and opens not only the parish government up to lawsuits but also its individual members involved with it.

“I just want y’all to be careful because this is garbage right here,” said Dove, who added he wasn’t opposed to the safety devices in school zones but the way the ordinance is being handled and agreed something needs to be done about speeders.

Vincent Dagate Jr., parish counsel, highlighted his concerns over the document — one being the distribution of funds derived from the program. According to Dagate, Blue Line Solutions, a Tennessee-based automated photo enforcement company installing the cameras, would receive 40 percent of the collected money.

“That’s approximately $6 million a year. Think about it: $6 million a year coming from the economic coffers of Terrebonne Parish and being deposited in Tennessee,” he said based on his calculations. “Our people are hurting right now. They’re hurting with the downturn in the oil and gas industry; they’re hurting from COVID. And yet, we are allowing this kind of money to be flown out of the state and out of the parish, more particularly.”

“In addition, it’s my understanding — and I’ve been told by the representatives of the sheriff — that the DA’s office is going to get 20 percent for his role in it. So that’s going to be another $2 or $3 million that’s going to be subtracted from that,” he continued.

It would violate Louisiana law if the district attorney, who would be made the hearing officer for the program, has a financial stake in the process, Dagate said.

Dove and Dagate argued that the Sheriff’s Office stands to make millions annually off the program, but it is the parish that’s unprotected if lawsuits are filed.

“When you go to court, he [Soignet] is going to be clear over here,” Dove said. “And I understand what the Sheriff’s trying to do: he’s going to make a lot of money with this, and he’s trying to protect the schools at the same time.”

“…[Soignet] may be receiving a net of $5 million, $7 million or so a year…He’s going to be brought into a lawsuit, and yes, it’s going to cost him half a million dollars or so to go through that lawsuit. But guess what: the Terrebonne Parish Consolidated Government is the one that’s going to pick up the tab,” Dagate said.

“He’s [Soignet] going to net several million dollars… and have a one-time payment of maybe $500,000. So from that perspective, it’s a good deal for the sheriff. And I don’t mean that disrespectful for the sheriff — the more power to him. But it’s not a good deal for the parish,” he added.

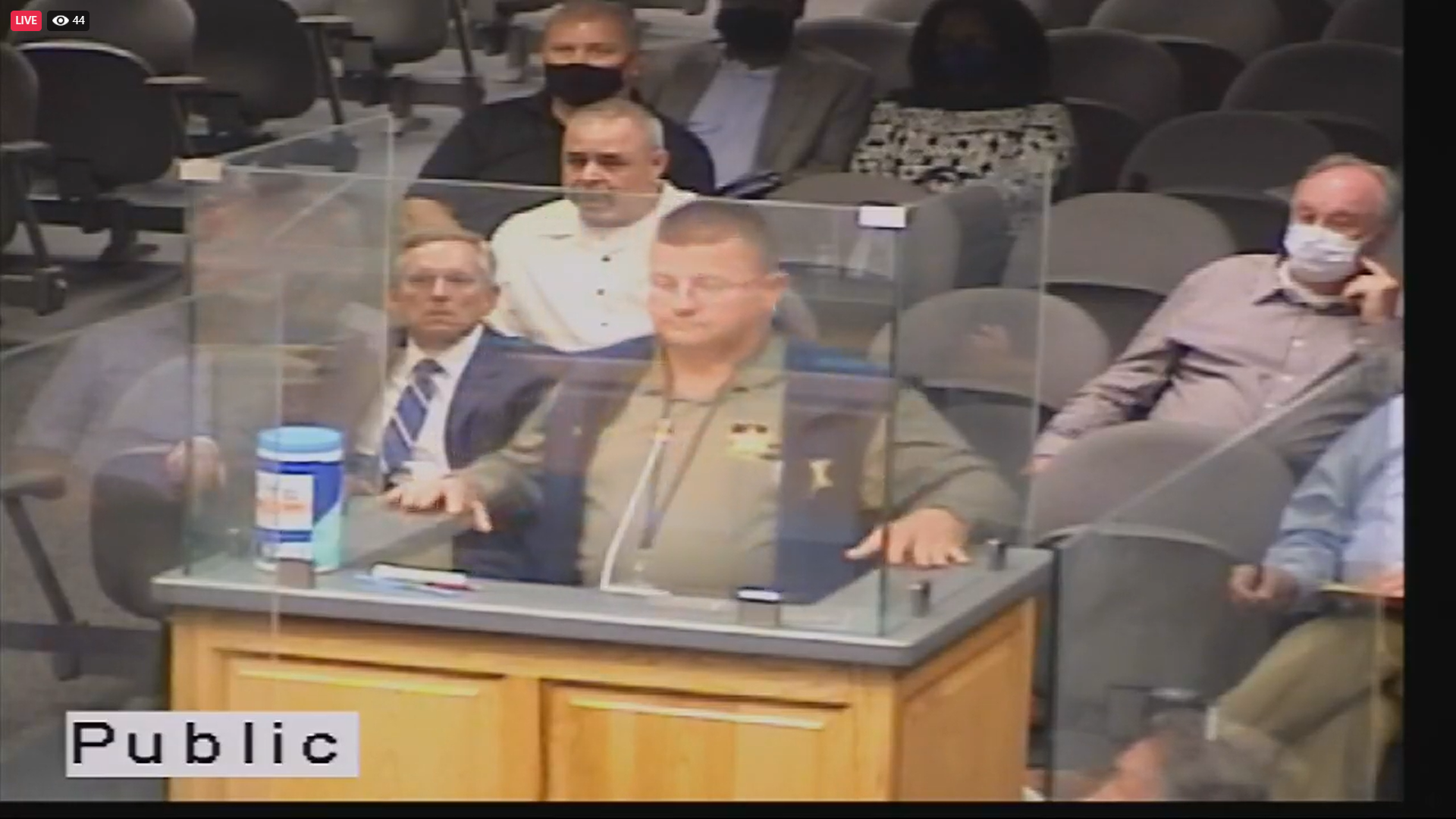

Soignet, and his legal representation, William “Bill” Dodd, contested the statements from the parish officials.

Soignet, and his legal representation, William “Bill” Dodd, contested the statements from the parish officials.

“As you all know, the sheriff collects millions of dollars every year in taxes for the parish…And that was one of the things we talked about with Mr. Dagate: that the sheriff is empowered to do that. The ordinance, as it was presented by Mr. Dagate, wanted the parish CFO to have the money that was derived from this ordinance,” Dodd said. “It was never a question about whether the money went to Blue Line and then to the parish. But there was a question about whether the parish ultimately would get their hands on it and then give it to the sheriff or whomever in accordance with the way, if there was revenue, it would be divided.”

Dodd went on to reference a section in the proposed ordinance that addresses the concern of distribution clarity, which reads: “All monies collected pursuant to this statute shall be collected by the Sheriff and placed in a designated Sheriff’s Office account, with all full access to same provided to the Terrebonne Parish Consolidated Government’s Fiscal officer, who will review said records on a monthly basis, and whose hourly time related to said review to be reimbursed by Sheriff.”

“We wanted to be as transparent as possible,” he said. “Nobody wanted to hide anything about this ordinance.”

Regarding the New Orleans lawsuit, Soignet said, the city was liable because there was no due process in enforcing the fines. “That was the first thing we squared away when it came to the legal aspect was due process.”

Dodd later added that his party did their due diligence when drafting the ordinance, even consulting with a major law firm out of New Orleans that deals in such constitutional matters and modeling it after language from other Louisiana cities where similar ordinances are already in effect.

“Are we concerned with the safety or what’s the greater good? Or are we worried about [when] doing our job every day if we’re going to get sued,” Soignet said. “I’m going to do my job, and I’m going to protect our community 100 percent as much as I can.”

As far as a designated percentage for the appointed district attorney that oversees the program, Dodd said that’s not the case. The hearing officer, or administrator, has no guarantee of a certain percentage because it “obviously would give them an incentive,” he said.

“There’s nothing wrong with the administrator getting paid. He just can’t be guaranteed anything,” Dodd said. “There’s no guarantee in this ordinance, and there’s no guarantee in a secret agreement that the district attorney has an X percentage…if he is the hearing officer. He will be compensated on an hourly basis for whatever work he does.”

Dagate and Jules Hebert, the parish’s main attorney, also took issue with the ordinance’s language that calls for the Terrebonne Parish Attorney to appoint the hearing officer in the program — as Hebert doesn’t have the authority to do so, they said. Dodd disagreed but said he is willing to find a solution with the parish attorneys.

Soignet was adamant that the proposed traffic violation enforcement system is not a money grab. “We had a meeting when we first started this…At the first meeting, a CPA that was hired about the parish president asked me three times, with Mr. Dagate, about money. I said it wasn’t about money. Everything [that’s been said] about money hasn’t come out of my mouth,” he said. “…This is not about money. It’s about safety.”

The two sides also debated the parish’s involvement in drafting the proposed ordinance.

“These are ordinances that are being submitted by the Terrebonne Sheriff’s team. They put this together. We did not insert any provisions…We didn’t proofread it or anything of that nature. They may have adopted a few of all ideas or suggestions, but that’s it,” Dagate said.

Dodd said the parish was involved in the process and believed they had a solution following the last meeting with council representatives. “The changes that were made were given to Vince [Dagate] to look at. We never heard anything back. We never heard anything back until the argument tonight,” he said.

Ultimately, in a motion by Councilman Danny Babin, the council decided to delay the ordinance until both sides could agree on it and then have said document sent to the Louisiana Attorney General’s Office for an opinion, which officials said could be done in 30 days, before returning to the council for a vote.

“We’ve been trying to compromise and make something happen,” Soignet said. “I don’t know how many times I’m going to have to come up here, but I promise you, I am not going to stop because the children deserve it.”