Alma Blanchard Miguez

December 8, 2011

Raoul Ledet Jr.

December 12, 2011Ralph Velez remembers the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

At age 14 on Sunday, Dec. 7, 1941, Velez took advantage of a day off of Holy Cross High School and walked from his home in the French Quarter to catch a movie on Canal Street. Before he left the theatre, his path of life had been irrevocably altered.

“I remember when I came out of the show, people were running around and all kind of stuff,” Velez, now 84, said. “That’s when I heard Pearl Harbor was bombed. People were on St. Charles Avenue storming the Japanese Consulate Office. From then on …”

From then on, everyone between the age of 17 and 45 had to register for the Military Draft. Not wanting to risk placement in the Army, Velez voluntarily enlisted in the U.S. Navy in January of 1945 after his high school graduation.

The war in Europe had ceased. But there was no end in sight for the Pacific Ocean warfare between Americans and Japanese.

Although he never engaged in combat with the enemy, the petty officer radioman on an assault ship was well aware that could change at any moment and the potential repercussion.

“Two of my friends in my neighborhood had gone into service right before me,” Velez said. “They were two brothers, and they both got killed volunteering to wipe out a German machine gun.” He said his cousin’s husband and his friend were also captured and held as prisoners in Germany and North Africa, respectively.

Velez was based at Subic Bay in the Philippines, where he said the natives were welcoming of American soldiers once they seized control from the Japanese.

Americans, who could purchase a carton of cigarettes for 50 cents on their ship, gave away tobacco and denim to the Filipinos, who happened to live in a strategic location and stood by during an American-Japanese battle in which more than 3,500 people were killed.

“They were thankful, I’ll tell you that, that you were there and the fighting was over,” Velez said. “Just a couple of months after the fighting ended, we were there and they came out of where they were hiding.”

For the most part, Velez’s ship was one of transport. The LSM carried “drums and drums” of aviation fuel and one time housed 15 to 20 prisoners that had to be transported from the Philippines to Guam.

The prisoners, who may or may not have been susceptible to the seasickness atop the Pacific, were prodded in that direction, according to Velez.

“The cook on the ship, he automatically knew what to do. He changed the menu, and instead of having whatever we were supposed to have that night, he fixed something that was a little on the greasy side. He did that so they’d get sick. They hardly ate anything after that for five days.”

Despite the lack of combat, Velez was able to compile a profile of the Japanese soldiers from the evidence of warfare he noticed at his various stops in the Pacific Ocean.

“My way of thinking, they were fanatics,” Velez said. “They wouldn’t give up. You could see the caves in the mountains were scorched. The only way you could them out was to blow them out with a flamethrower.

“They were indoctrinated. They were told if the Americans got them, we would eat them. When the Americans did get there, (Japanese civilians) just went out in the ocean and just started swimming away. There was nowhere they were going to go. The sharks got them and some were jumping off cliffs.”

Velez’s active service ended nine months after it began when President Harry Truman authorized the use of an atomic bomb on two occasions. Many people have criticized the decisions as heinous crimes against humanity, Velez said he feels like the bombs saved his life.

“I know if the president at that time, Harry Truman, if he wouldn’t have dropped that atomic bomb in Japan, which some people are against, I may not be here today, because I would have been in that invasion of Japan,” Velez said.

Velez served nine additional months in the Navy after the war ended before returning home to New Orleans.

He began working in a clerical position with U.S. Department of Agriculture and was tasked with making sure government loans to cotton farmers were based on the correct weight and price.

Velez relocated to Houma three years ago, one year after his wife died, to live with his grandson.

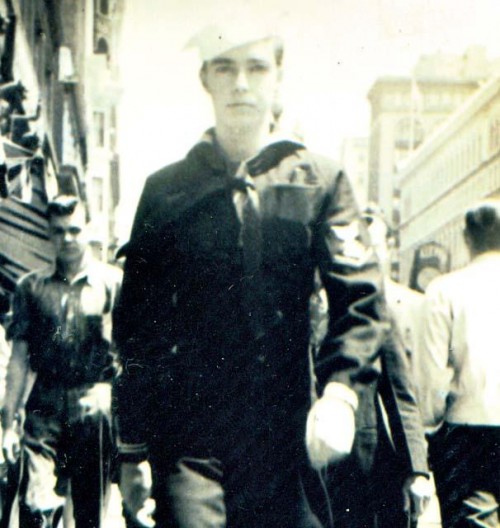

Navy radioman Ralph Valez enjoys a break from the action.