Not their finest hour

September 30, 2015

UPDATED: Injured football player ‘responding’, but still in critical condition

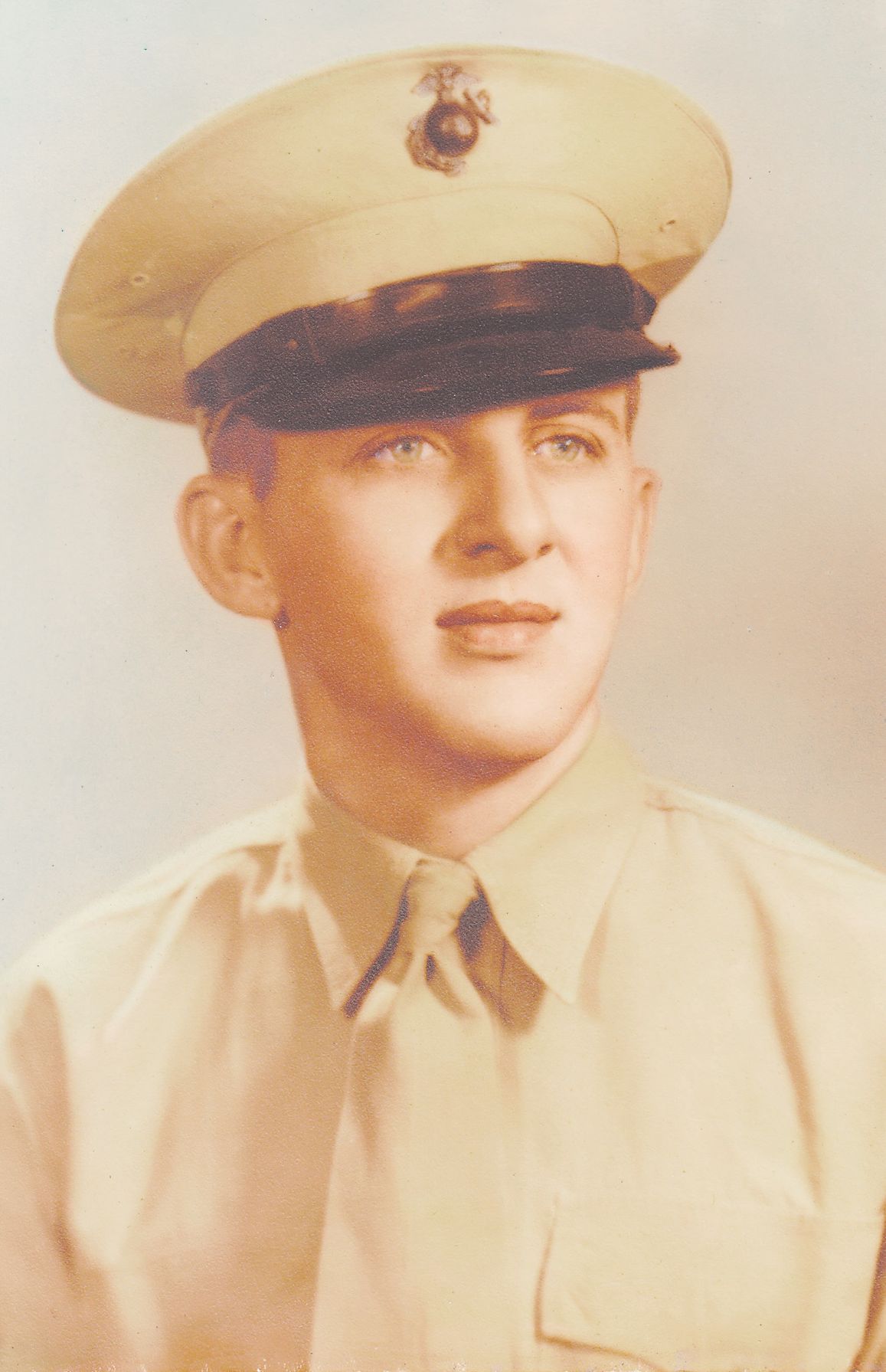

September 30, 2015Tillman “T-Man” Andrew Chauvin was born on Oct. 11, 1925, the youngest of 10 children, to Eldrick & Agnes Chauvin. The Chauvins lived in Daigleville, which is now simply known as East Houma.

Tillman’s father died of cancer when he was 12-years-old, so he left sixth grade to help support his family. He delivered meat for his brother-in-law, Donald Billiu, owner of Billiu’s Meat Market, on a bicycle throughout Daigleville.

A teenager when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, Tillman witnessed an event that ensured the United States would enter WWII. In 1942, he was inspired to join the U.S. Marine Corps by an Uncle Sam poster. He lied about his age to his recruiter (he was 17) and headed for the Naval Training Center San Diego.

Tillman would fight in two key battles of the Pacific Theater.

He didn’t speak much with his family about his time spent fighting the Japanese during the battles fought to recapture Guam and Iwo Jima against Japanese forces that considered surrender a worse fate than death. But his discharge papers reveal all that needs to be known.

“He was really proud of his military [service],” said his son, Kerry Chauvin. “He wasn’t very talkative about it because he had a lot of bad things happen to him in the military, not only to him, but to his best friends. A lot of them passed away.”

Tillman was tasked to the 3rd Marine Division, which was part of the invasion force to retake Guam.

The battle pitted 59,401 American soldiers and Marines against 18,657 Japanese infantry and tank operators.

Tillman’s first experience of battle started with an amphibious landing on the island on the morning of July 21, 1944. Twenty of the amphibious landing vehicles were sunk by the Japanese that day. Over the course of the next 20 days, Japanese soldiers fought fanatically, rushing the marines on the beachheads during night raids, running head-on into American light-machine gun and rifle fire.

Two days after landing on the beach, Tillman was shot in the right foot. That bullet remained in his foot until the day he died. He was awarded the Purple Heart.

By the end of 20 days of fierce fighting, 18,337 of the Japanese forces were killed.

Tillman went into his Pacific tour of duty a rifle squad leader, but was promoted to Corporal between Guam and Iwo Jima.

He and the rest of the 3rd Marine Division left Guam the day it was declared secure to prepare for the critical and historic invasion of Iwo Jima. Tillman’s foot healed before the invasion started and on February 19, 1945 he was again in an amphibious lander heading toward a heavily defended beach.

The island was heavily fortified with pillboxes, caves and covered artillery emplacements. The Marines made progress slowly. The Japanese fought without regard for their own lives, even surrendering only to pull the pin on a suicide grenade, killing themselves and U.S. soldiers. Rifle fire proved relatively useless against the fortified Japanese, so the Marines resorted to using grenades and flamethrowers to flush them out of their bunkers.

Tillman and the rest of his division was relieved by the Army before the Pulitzer Prize winning photograph, “Raising the flag on Mt. Suribachi,” was taken, but Tillman saw some of the worst fighting in the Pacific.

He was discharged a month later and returned to Daigleville, where he began working for Schlumberger as an operator in a career that would span 37 years.

Not long after coming home, Tillman’s niece set him up on a blind date with Shirley Dill.

“He was blonde, and [had] beautiful blue eyes,” Shirley said. “He was a little raggedy from just coming back. He was wearing civilian clothes. He was supposed to be in uniform, but he wasn’t.”

Three months later, the two were married. Together they would raise three children: Kerry, Pamela and Deborah. They were married a total of 70 years.

Tillman was a true gentleman. He never spoke ill of anyone and never cursed, said his daughter, Deborah Bergeron.

“But when he said ‘Damn it,’ you’d better run,” she recalled.

He loved his family more than anything. When he was home from working offshore, the whole family would visit with friends together, instead of crowding around the television. After retiring from Schlumberger, he would watch his grandchildren, instilling in them the values of hard work, honor and a love of family.

He considered education paramount to his children’s success.

His children agreed this was likely because he did not complete his own education. His son, Kerry, went to Louisiana State University to study engineering and business and later became the first president of Gulf Island Fabrication, a fact he was very proud of.

Deborah became a teacher at Lisa Park Elementary after graduating from Nicholls State University in education.

Tillman was a self-taught man.

He taught himself how to draw blueprints and a bit of all construction trades. He would build boats at home, willing the wood into shape using hot water. He even fixed his car himself.

“He only had a sixth grade education, but could build a boat from scratch,” Kerry said. “Believe it or not, he was a master in mathematics.”

“Daddy never hired a carpenter,” said his daughter Pamela Louviere. “He could always do all those things. He could figure out how to do the electrical. He added on to the house and did all the work from pouring the cement to plumbing.”

Once, Pamela recalls, her father was fixing a broken pipe under his house that had burst during a hard freeze. A plumber passed in his work van and yelled to him from

behind the wheel that he couldn’t perform that job himself and that he had to hire a licensed plumber.

“I got worried,” Pamela remembers. “And he yelled back, ‘I’ll tell you what, get out that truck and come fix this!’”

With that, the plumber didn’t press the issue and drove away.