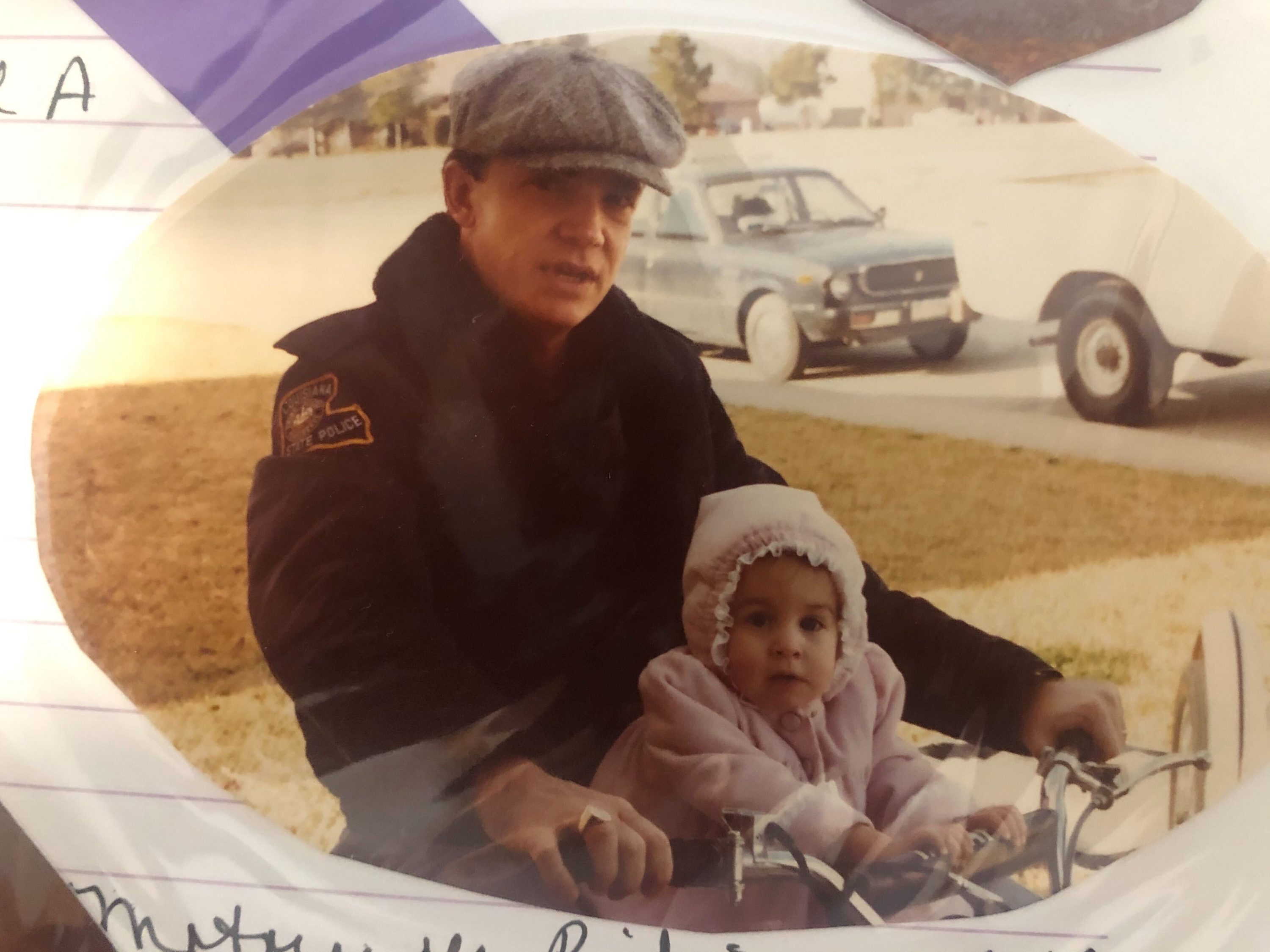

Mahlon Joseph Bourgeois

July 7, 2009

Ronnie Jerome Labit

July 9, 2009Louisiana’s best hopes for coastal restoration – large diversion projects that capture sediment from the Mississippi River – won’t prevent the state from continued land loss, according to two Louisiana State University geologists.

But those findings, published in the “Letters” section of Nature Geoscience magazine, are not an argument for giving up on rebuilding our coast. Instead their findings and further research should be used to focus efforts where they can do the most good.

Harry Roberts, an LSU geology professor, and Michael Blum, a former LSU geologist who now works for ExxonMobil Upstream Research in Houston, predict that Louisiana will lose an area the size of Connecticut by 2100, even with large diversion projects. Sea level is rising three times faster than during delta-plain construction, their paper says.

Even if the Mississippi River was carrying as much sediment now as it did then, the researchers say, it couldn’t compete with natural and manmade forces that are causing the Gulf to move farther inland. What’s more, the Mississippi and Atchafalaya rivers carry only about half the sediment that they did 100 years ago because of dams and reservoirs built on waterways that feed them.

Given the limited supply of sediment, it’s critically important for Louisiana to capture as much of it as possible and to use it where it will be most effective.

State officials and the National Academy of Sciences have urged a study of the Mississippi’s ability to sustain wetlands over 100 years or longer, and that’s the kind of research that could help guide plans.

An academy National Research Council panel that is reviewing the Army Corps of Engineers’ Louisiana Coastal Protection and Restoration Study has recommended a sediment budget for the river. The corps says that it’s conducting its own study of the Mississippi’s sediment load and its ability to rebuild wetlands. That’s a necessary step.

Good information is only part of the answer, though. Louisiana officials will have to set priorities and make some difficult decisions about what can and can’t be restored. The dire picture painted in this report should only lend urgency to this vital cause.

– Times-Picayune (New Orleans)