Waffle House shooting draws sharp response from Sheriff Larpenter

September 20, 2016

HPD officer accused of theft in civil lawsuit

September 20, 2016What could have been a protracted dispute melted into compromise and a moment of prayer at the Terrebonne Parish jail last week, as law enforcement officials and a Native American tribal leader reached agreement on a hairy question of protocol versus religious beliefs.

It all began after Adrienne Matherne of Houma pleaded guilty in connection with a series of camp burglaries in Dulac and Chauvin, and was sentenced to prison time, requiring that her long, black hair be shorn. The problem is merely cosmetic for most inmates, a requirement officials say is justified due to health and safety concerns.

But for the 30-year-old Matherne there is a complication. Her family adheres strictly to traditions passed down through generations of the Grand Caillou/Dulac Band of Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw people. Her sister, Shirelle Parfait-Dardar, is the tribe’s chief.

“Our parents would have had seven children and four of us survived” Parfait-Dardar said. “One child prefers to learn through experience rather than advice. We love her and pray for her and we are asking the creator that this be the death of her old life, so that when she gets out she is going to be reborn. She accepted responsibility for what she has done. She did not run from it.”

When she learned that her sister’s hair would be cut, Parfait-Dardar made contact with parish jailers, to find out if there was an alternative. The problem lies with tribal custom and religious belief, which is that hair should not be cut if possible. If it must be cut, then one’s mother must do the cutting. The tradition is so strong, Parfait-Dardar noted, that mothers must designate who the next person in the family will be to do the shearing if they are unable to do so, due to death or incapacity.

Bill Dodd, the attorney who represents the Sheriff’s Office, supplied the chief with a Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals ruling that arose from a lawsuit brought by a Texas inmate. It is consistent with most higher court rulings on the matter, that when it comes to things like hair security and safety must come first, and that in a conflict between the rules and religious belief – in most cases – tradition must yield.

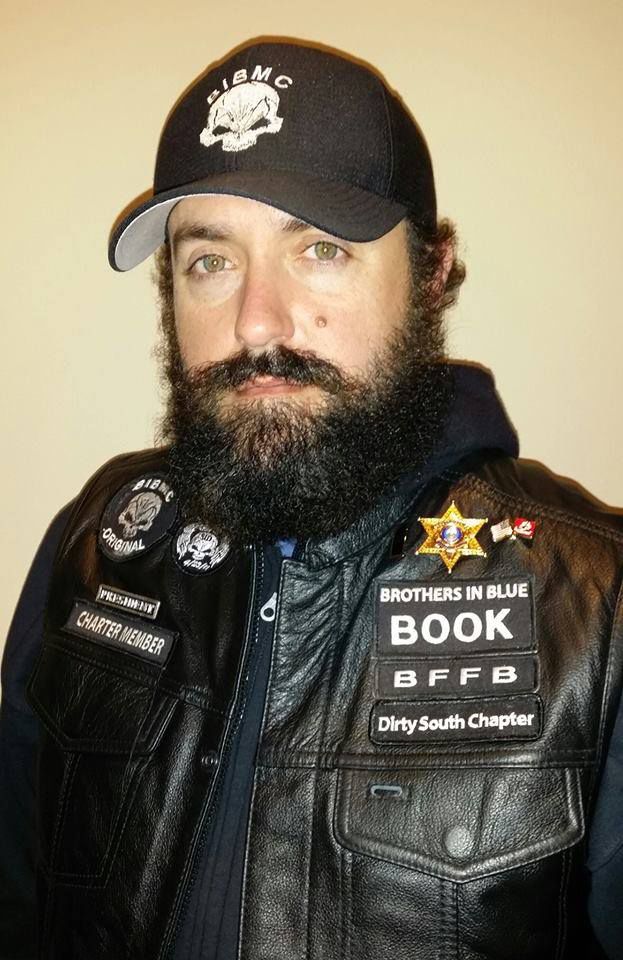

“The problem we have so many people that come through with different hair and if we didn’t have any type of policy and procedures to do something with hair we would have people smuggling weapons and drugs with hair,” Sheriff Jerry Larpenter said. “The ruling lets us manage haircuts. But if people have a religious belief we want to accommodate it to a certain degree.”

The accommodation was reached without much difficulty, Parfait-Dardar said Larpenter agreed that Matherne’s hair, once shorn, would be placed in an envelope and given to the chief. That was acceptable, Parfait-Dardar said, because it would allow her mother to bury the hair in a special place, in accordance with custom.

“I want peace and love and respect and understanding,” said Parfait-Dardar, which is what she feels she got from Larpenter’s office. “We need to stop dividing ourselves, we are all brothers and sisters. Our hearts were a little broken but they gave me very good reasons. When I told them if it has to be cut we have a procedure in place to do that they wanted to help. They could have said we don’t have time for that.”

The teachings on hair, Parfair-Dardar said, are rooted in its being seen as an extension of the nervous system.

“There is great strength in growing your hair,” she said. “There is better insight, because it is seen as a part of the body. When it is lost it must be returned to earth, because earth is the mother of all of us.”

Law enforcement’s enumerated reasons for control over hair range from elimination or prevention of lice or other infestations to deadlier consequences. Hair, officials acknowledged, can be used as a weapon in some cases, or if it is long enough for doing self-harm. The accommodation given to Parfait-Sardar and her family, authorities acknowledged, was not a big departure from an on-going practice in any event. The hair that is shorn from inmates at the jail is in most cases donated to Locks of Love, which uses it to make hair-piers for people who need them for reasons such as loss due to medical treatment for cancer.

“We have to be able to adapt,” Parfait-Dardar said. “Even though we have out specific ceremonies we all live on the same planet and we are a tribe do not live on a reservation. We have to follow the same laws as everybody else.” •