A bridge too far: Pending bridge closure unacceptable to hamlet’s residents

May 3, 2017

More Good spreading good throughout US

May 3, 2017The question of whether the rights of black voters are violated by the practice of at-large voting for judges in Terrebonne Parish is now fully in the hands of a federal judge, whose verdict is expected in August.

Friday afternoon more than one hundred black men and women from Terrebonne Parish packed a third-floor courtroom at the Russell B. Long Federal Courthouse in Baton Rouge, to witness the last day of testimony in an eight-day trial that stretched over two months. Many came from in busses chartered by local churches.

U.S. District Court Judge James Brady, who sat through testimony that ranged from nearly superfluous to highly emotional, will be reviewing thousands of pages that are now part of the trial record, to determine whether the at-large voting scheme used for decades in Terrebonne Parish violates Section 2 of the U.S. Voting Rights Act, and to some degree whether that can be cured by establishment of a minority sub-district.

Ultimately, it is the lengthy testimony of experts and their eye-glazing, voluminous reports on matters historical and statistical that will most aid Judge Brady’s decision-making process.

LEGAL TALENT

The attorneys who brought the case to the court are veterans of Section 2 litigation, and traveled a long way for the presentation. Leah Aden and Victorien Wu are staff lawyers for the New York based NAACP Legal Defense Fund. Michael deLeeuw is a litigation specialist at Cozen O’Connor, an international law firm known for a commitment to social justice and ranked as one of the top 100 firms in America. Ron Wilson of the New Orleans Blake Jones law firm has demonstrated a career devoted to civil rights issues.

“This case raises fundamental legal questions about the equality of opportunity for black residents in Terrebonne to participate in the democratic process generally, and the impact on black voters in particular,” Aden said in her opening statement before U.S. District Judge James Brady. “At large voting in Terrebonne operates as a structural barrier that denies black voters an equal opportunity to elect their candidates of choice.”

Assistant Attorney General Angelique Duhon Freel presented most of the state’s case at trial. A former member of the Murray Law Firm in New Orleans, which specializes in complex litigaton, Freel has handled several high-profile cases for the Attorney General’s office, including its attempt to block same-sex couples from marrying, prior to the landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision striking down such bans. Madeline Carbonette, who like Freel, has worked voting rights cases on behalf of the Attorney General, was another part of the team.

In her opening, Freel maintained that neither her boss nor the governor have the power to change how Terrebonne judges are elected. Even so, she said, changing the system would strip some people of the right to elect all five judges in the parish. Additionally, she said, proof that voting rights were violated in Terrebonne does not exist “in the last six elections.”

A proposed cure for the alleged violation – creation of a sub-district with a majority of black voters who would elect one of the court’s five judges – would result in racial polarization, Freel said. She maintained as well that the plaintiffs will not meet the requirements for a minority sub-district as Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act requires.

WAR OF EXPERTS

One of the experts Freel and the other members of the Attorney General’s team presented was Michael Beychok, a veteran political consultant who analyzed bi-racial campaigns in Terrebonne.

Acknowledging that race was indeed a factor in the losses of black candidates, “money, time and people” were seen by Beychok as the most important currency which black candidates did not produce in sufficient quantity to ensure victory.

Too much emphasis was placed on race in drawing the lines, rather other considerations including shared interests, Beychok said.

Ronald Weber, a distinguished professor of government, social science and related topics, was the centerpiece of the Attorney General’s expert presentation and testified last in the state’s case. Weber has served as a consultant for various local governments in matters of redistricting.

In particular, he found fault with a proposed solution to voter dilution in the at-large system, prepared by an expert for the plaintiffs.

Black voters, while numerous enough in Terrebonne, do not all live in naturally contiguous areas. The district was therefore not compact, as is required according to prior cases, in the opinion of Beychok.

Another defense expert, Michael Hefner, referred to the proposed minority sub-district drawn to show that one could be created, as “racial gerrymandering.”

Defense partisans pointed to the election of Juan Pickett, a black attorney, as a judge in the 32nd District. There were also suggestions throughout the trial that Pickett’s unopposed status was tacitly agreed to by powerbrokers in Terrebonne as a way of pushing a broomstick in the spokes of the case.

Pickett, plaintiff’s witnesses had testified, could not be characterized as a choice of black voters because he ran unopposed. Weber agreed with an assertion advanced by Beychok, that Pickett had won – and dodged opposition – because he came to the race early with a substantial war-chest, scaring off other potential candidates.

The results of elections past, however, show where some qualified minority candidates for judge did well in black election districts, but faltered or failed in predominantly white areas. Plaintiff witnesses testified that with no chance of winning black candidates would tend to campaign more directly and aggressively in black neighborhoods, a practice opposite of what defense experts said is needed for victory.

Experts for the plaintiffs have indicated through maps, diagrams and statistical information, proposed drawing of districts that would meet the requirements for a minority sub-district and one or more non-minority sub-districts, in their opinions. The plaintiffs also cautioned several times during the proceeding that to meet the threshold of how the act should be administered, they need only show that remedies are possible, leaving the fine tuning to the legislature or some other body.

SLIGHTS AND STARTS

The emotional testimony Judge Brady heard about Terrebonne Parish’s overall history of racial discrimination set a foundation for the case, required for presenting such a matter before the court. Other history, closer to the present time, was a part of the case as well. The disciplining of retired judge Timothy Ellender for wearing a Halloween costume consisting of a jail inmate’s orange jumpsuit, along with shackles, blackface and an Afro wig came up on several occasions. Plaintiff attorneys note that even after the display and widespread negative publicity Ellender was elected to another term on the bench. Among witnesses questioned about that time was Judge Pickett, who was asked if he found the outfit offensive. worked closely with Ellender and testified said under cross-examination that he indeed found the reports of the outfit – he never saw it himself – offensive.

Pickett did not volunteer – and he was not pressed by attorneys – about the actual testimony he gave before the Louisiana Judiciary Commission. The transcript from the hearing on Ellender from that time shows Pickett saying that he was not offended on two separate occasions of questioning.

Houma attorney Timothy Ellender Jr. – son of the retired judge – spent a brief time testifying as well. Called by the defense, Ellender Jr. testified that the NAACP’s Boykin told him he would make a good candidate for judge. The suggestion was that Boykin would have wanted Ellender to run against Pickett. Boykin and the NAACP attorneys dispute the claim.

Old history accounts continued as former legislators testified about an attempt in 2011 for establishment of a minority sub-district through a house bill.

BIG PRICE TAG

Terrebonne Parish President Gordon Dove – then a legislator – described the bill as well as the current effort to seat a minority judicial candidate as “trying to shove something down our throats.”

Dove has strongly opposed attempts to create a minority sub-district. He has cited concerns in particular that if the 32nd Judicial District is set up for five-judge elections the parish will bear great expense, in particular for re-programming voting machines.

He has referred to the proposal as a plan for “Balkanization” of Terrebonne Parish. So concerned is Dove about the potential of districting for the local judgeships that he has had Parish Attorney Julius Hebert attend each hearing on each day, charging an in-court lawyer’s fee plus expenses.

Terrebonne Parish is not a named defendant in the suit, and was blocked by Judge Brady from intervening, or essentially making itself a defendant.

The attempt to intervene in the case, Dove had said, was merely an attempt to have “a seat at the table.”

Had Terrebonne become a party to the action, a loss by the state could have resulted in voluminous legal bills. Despite the rebuff, Dove continues to make the fight his own, committing legal resources in the form of parish attorney Julius Hebert, who is closely monitoring the proceedings. Despite not being involved, Terrebonne is invested at this point, if nothing else through the cost of the legal representation.

The attempt to intervene as well as Hebert’s ongoing monitoring in court had by last Monday cost the parish $43,713.77, money Dove says is well spent.

“It would be wrong for me not to do everything I can to stop this, and to be informed as well as possible in case the judge allows the minority sub-district,” Dove has said in interviews during the course of the trial. “I would be lax in my duty as parish president not sending our legal people up there. The people of Terrebonne Parish have a stake in this. You have a group from New York City with the NAACP and you have individuals trying to completely rearrange and devastate our judicial system as we know it. We have to send Julius to find out what they are trying to do to our judicial system, trying to run it the way they want it and not the way the people in Terrebonne Parish want it or how it has been for however long it has been in place.”

UNUSUAL ACTION

According to experts on Section 2 litigation Judge Brady’s task, to determine whether the state is violating federal law through at-large voting for Terrebonne’s five judges, does not require involvement of the parish. Experts who have published on Section 2 litigation in various parts of the U.S. and have represented parties in them question why any entity not named in such a suit would wish to be a part of it.

“That is unusual,” said Ed Still, a Birmingham attorney who has litigated Section 2 cases for 45 years. “I don’t think I have ever been involved in a voting rights case where somebody who is not a party is there every day. You might have the local gadfly or a scholar who wants to know something. I can’t think of a county or any other governmental entity that has tried to get into a voting rights case as a defendant as opposed to getting out of it.”

Terrebonne Parish NAACP President Jerome Boykin said that all he has observed increases his confidence that Judge Brady will see the plaintiffs’ argument as being correct.

“I think after the trial we are one step closer to having a minority judicial district,” Boykin said after the proceedings were complete. “It feels good and it is going to feel even better once we get a favorable decision in this case. I am more confident now than ever before. I knew all along we had a great case to win. After seeing these attorneys in action, I am more confident now than ever before.”

After court adjourned on Friday attorneys on both sides got busy preparing post-trial briefs, which the judge requested in lieu of in-court oral closing statements. His decision is expected to be handed down in August.

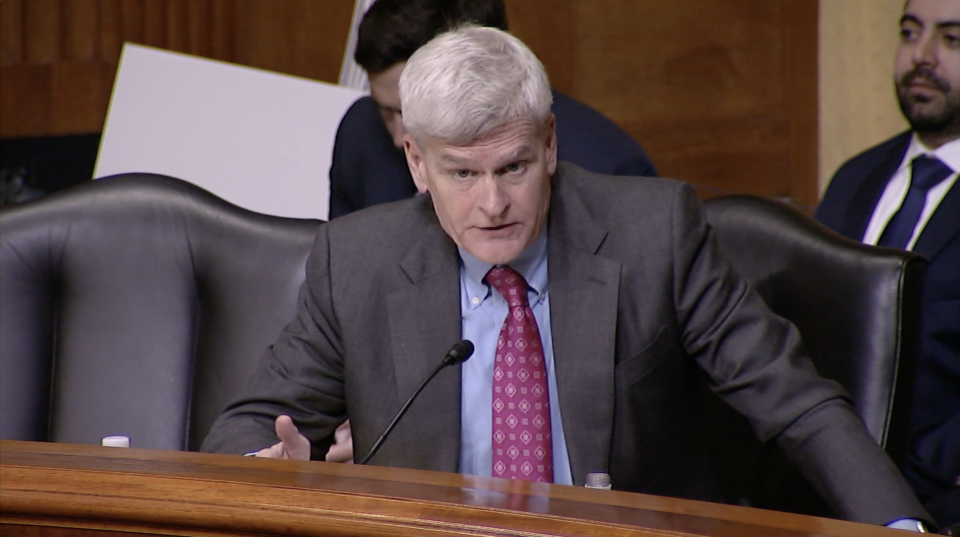

NAACP members and local supporters gather at the Russell Long Federal Courthouse in Baton Rouge on the last day of testimony in the NAACP v. Jindal voting rights case.