Situations teach us about life, how to live it

December 10, 2014Hardee’s seeking toy donations

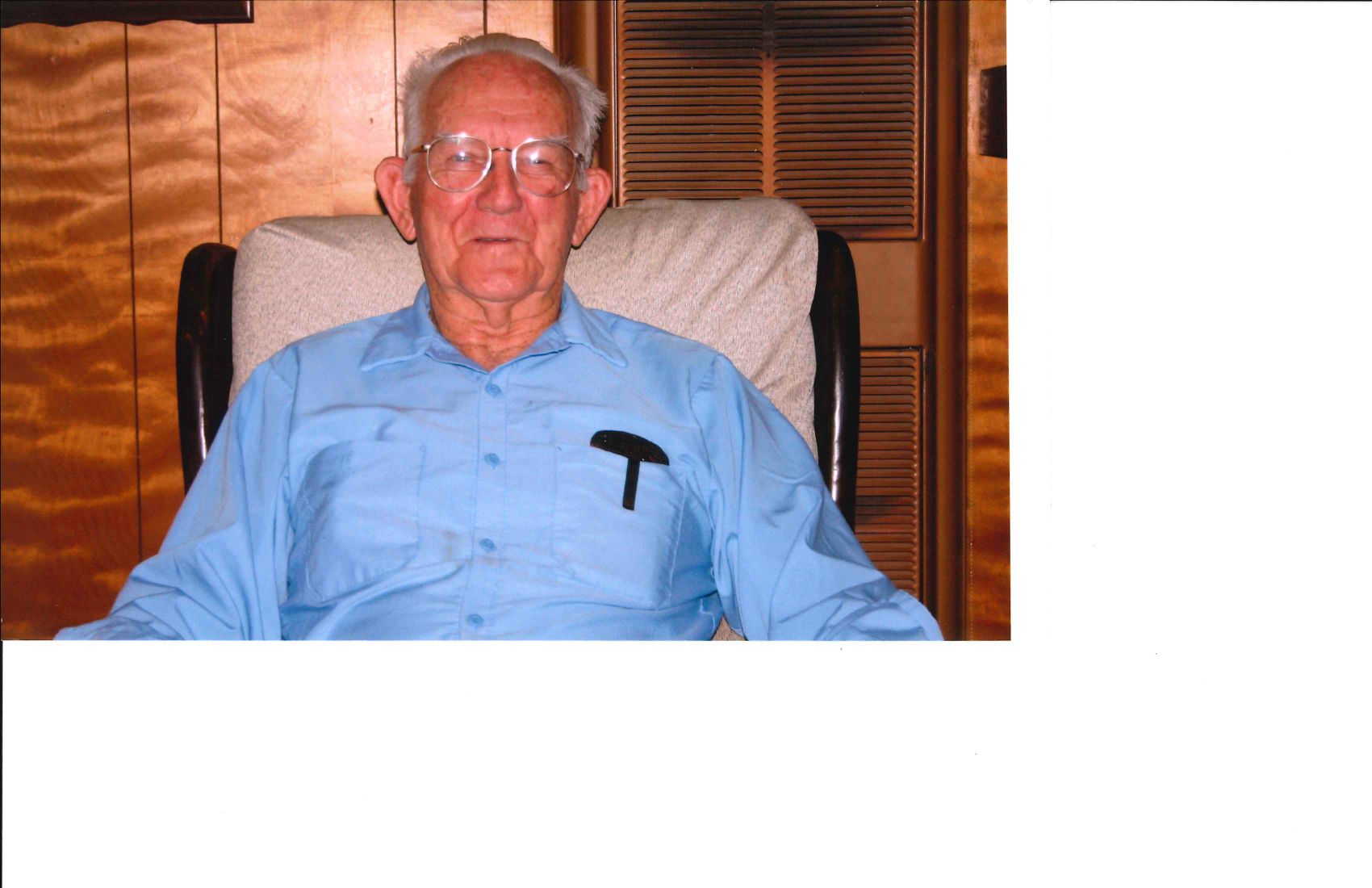

December 10, 2014They called him the Pumpkin Man of Bayou Blue.

But Earon John Poincot, who died last Thursday at the age of 95 after a long illness, was, according to the recollections of friends and family much more than that, a multi-dimensional good neighbor and entrepreneur, who is among the last of a literally dying breed.

“He had a hard shell, but he was soft underneath,” said one of his sons, Lloyd Poincot. “He did what he had to do, when he had to be tough and hard. But there was a great deal of softness inside of him.”

Andrea Poincot, who is married to Earon’s grandson, Randall, recalls him as dedicated and delighting in bringing smiles to the faces of her own children.

“He had concerns for all people, it wasn’t just family, it was everyone in the community, especially the church,” said Andrea, noting time he spent aiding St. Louis Catholic Church, where his life was celebrated at a funeral Saturday. “He had a very fulfilled life of service, with love for his family and love for his God.”

He grew up on his family’s farm, located north of La. Highway 182 near Bayou Blue Road, straddling what is now U.S. Highway 90. The family still farms about 20 acres on the property.

Hard times began for Earon from the moment of birth, relatives said.

“He was born at the house in Bayou Blue at the hands of a midwife, and she had so much difficulty she couldn’t deliver him,” Lloyd said. “She sent for a doctor.”

The baby survived, and joined his family early on in their farming endeavors, leaving school in fourth grade.

When Lloyd, who was born in 1944, began working the farm as a pre-teen there were about 40 head of cattle.

“He had a black Angus bull he would breed with the mama cows, and there were all different mixes,” Lloyd said.

The cattle were driven in trailers at culling time, sent to either Raceland or Thibodaux livestock markets.

At harvest time Earon would drive the corn, potatoes and other crops to the French Market along the Mississippi River in New Orleans, sometimes taking one or more of the children along, gripping the wheel of the truck with big, heavy hands made tough from working the earth.

There were blankets for sleeping, a necessity sometimes if the produce was not completely sold on the first day.

The truck that brought produce to market was also used to bring family to Grand Isle for summer outings, with all of the children piled in the bed for the trip.

“Times were hard back then, and he had to work and work and keep working,” Lloyd said. “Once in a while he would take time off, and that’s when we would go to Grand Isle. We got to play on the beach, bury each other in the sand, eat chicken eggs and have crab boils on the beach.”

Sometimes Earon took the family to Robinson Canal, near Cocodrie, where they would fish and crab. A 1950 black Ford was the vehicle for those outings.

Changing needs of the community brought change to the farm, and when the property was split by U.S. Highway 90 the cattle had to be given up, because the farmland was split in two with no access to the northern parcels, Lloyd II said.

“He was afraid his cattle would get on the road,” Lloyd II said, recalling his father’s sadness. “He looked as someone would if somebody pulled out one of your eyes.”

Earon and his wife, Lydia, who died last year – they were married for 74 years – found a way to overcome the sadness of giving up the cattle with a new diversion.

They set up a roadside pumpkin stand at pumpkin harvest time; one or the other would sell the pumpkins, upon which Lydia had painted faces.

That was how a lot of people in Bayou Blue came to call Earon the Pumpkin Man, and Lydia the Pumpkin Lady.

There was another source of fame for Earon that was born of innovation.

He had loathed horses all of his life – largely because of the work he had done with them and with mules as a boy on the farm – and he liked the idea of farming mechanization.

He was the first person in the area to own a tractor with a backhoe.

“Bayou Blue was growing, and they didn’t have treatment plants. They had to have cesspools dug,” said Lloyd. “That was back in the 1960s, roughly. Nobody in the area had anything like that, unless they got a contractor. He charged $20 per hole and buried anything from septic tanks to horses to cows, and he dug big ditches.”

A neighbor who raised racing horses, some valued at $10,000 or better, Lloyd said, often used his father’s services for horse burials.

Earon drove a bus for the Terrebonne Parish schools for many years. While he was not a man of music, Lloyd said. His father would bring a battery operated radio onto the bus, which seemed to keep students quiet and behaving.

For much of his younger life, Lloyd said, he only saw the tough side of his father, the task-master who learned from past tragedies of crop loss that farming was a deadly serious business.

“It wasn’t until I left for the military that I saw that other side of him, that I saw him cry,” Lloyd said, recalling the trip with his mother and father to the bus station for his trip to New Orleans and points beyond.

After that, Lloyd said, he began to understand the reasons for his father’s strict disciplinarian stance. Although a loving parent, he neither spared the rod nor was going to permit any child to be spoiled on his watch.

Growing up on a farm is a challenge, and the children of Earon Poincot said growing up on their farm was a particular challenge as well.

Knowing how hard Earon worked to stand on his own two feet made it difficult for some family members, Lloyd said, to see him in a nursing home setting where he had no control.

But relatives said they would not have changed anything, that Earon gave them lessons of value that they have carried throughout their lives.

The importance of independence, Lloyd said, was the lesson over everything else that his father taught him, not only by words but example.

“I wouldn’t trade any of that for any other family, not even a Rockefeller,” Lloyd said.