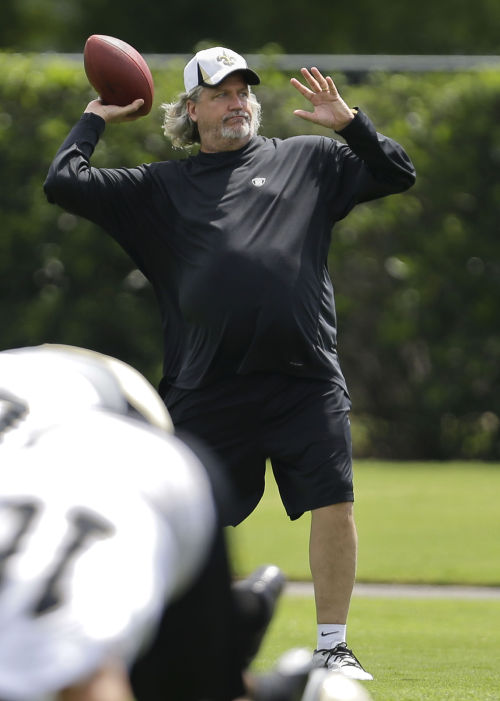

Defense the focus of Saints’ mini-camps

May 28, 2013Housing authority cited for 11 items

May 28, 2013It started with a complaint against a senatorial campaign’s handling of contributions, brought by a Washington, D.C., watchdog group.

It will end with adjudication of a federal criminal charge brought against the scion of a Houma marine towing company.

Arlen “Benny” Cenac will enter a plea at an as-yet-undetermined date before a federal magistrate when he answers an allegation that he lied to the Federal Election Commission about contributions he made to the campaigns of Sens. Mary Landrieu, D-La., and David Vitter, R-La., in the names of relatives and associates authorities say had no knowledge of the ruse.

Federal election laws limit the amount of money an individual or a company may contribute to a candidate. The underlying allegation is that Cenac had attempted to give more money than is legally allowed to Landrieu and Vitter by making it appear the money had come from other people.

If convicted, Cenac faces a maximum term of five years in prison, a $250,000 fine and three years of supervised probation following his release.

U.S. Attorney Dana Boente filed a 1-count bill of information against Cenac, alleging “between Feb. 16, 2008, and May 24, 2008, Cenac, who is the president and owner of Cenac Towing, submitted cashier’s checks that he purchased in the names of individuals other than himself to the campaigns of two United States Senate candidates.”

The bill of information is an accusation, similar to a grand jury indictment, but brought only by a prosecutor.

“The money Cenac used to purchase these cashier’s checks came from personal and corporate accounts,” a statement from Boente’s office reads. “In submitting these contributions to the campaigns, Cenac neither obtained nor sought the knowledge, permission or authority of the individuals he listed as remitters on the cashier’s checks.”

This, according to court papers, caused a knowing and willful “submission of a materially false, fictitious, and fraudulent statement and representation, that is the submission by unwitting authorized campaign committees of candidates for the United States Senate to the Federal Election Commission of a report that was materially false in reporting the source and amount of contributions to the campaigns.”

Cenac Responds

Cenac’s Washington, D.C.,-based attorney, Kwame J. Manley, said since July 2011, his client “voluntarily resolved all issues with the FEC and paid a civil fine in connection with the case.”

“The bill of information filled yesterday is part of Mr. Cenac’s agreement with the Department of Justice to resolve the remaining aspects of this matter,” Manley said. “Mr. Cenac has learned from this experience and looks forward to implementing enhanced procedures to ensure full compliance with election laws in the future.”

The $170,000 fine Cenac paid the FEC, according to its officials, is a whopping record.

But the FEC matters were civil in nature, arising from a complaint by Melanie Sloan, executive director of Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington, which monitors campaign contributions and practices.

In 2009, Sloan and other people affiliated with her group noticed something unusual while poring through campaign finance reports.

A large sum of money had been given from Landrieu’s campaign to the U.S. Treasury. And there was no explanation.

“Suddenly giving up $25,000 in contributions was suspicious,” Sloan explained. “When somebody gives back money, they usually explain. And they usually give money back to the donor. It is only when a campaign believes it is something illegal that they give it to the treasury. (Landrieu) didn’t explain that so we wondered what was going on.”

Devil in the Details

After Sloan filed a complaint with the FEC, on Nov. 20, 2009, an investigation commenced.

The Landrieu campaign responded to the complaint in January 2010, stating that it had received “a series of six contributions payable by cashier’s checks issued by Whitney National Bank in New Orleans. … The contributions, which totaled $25,300, were forwarded to the committee by a Louisiana attorney.”

The Landrieu campaign made its own inquiry, which included calls and letters to the named contributors. When one was contacted and said he had not made such a contribution, the Landrieu campaign staff determined something was not right. But that resulted in another problem. Since they could not ascertain the identity of the real contributor, there was nothing left to do but turn over the money from the entire series of contributions to the Treasury.

The FEC found that argument compelling, and a determination was made that the Landrieu campaign had violated no laws, and acted appropriately in giving the money to the Treasury.

But that still left an open question of who had actually made the contributions, if the people whose names were on the cashier’s checks didn’t make them. The people named as remitters on the cashier’s checks were Roger Beaudean, general manager of Cenac Offshore LLC and his wife, Lynn A. Beaudean; Travis Breaux, manager of Southern Fabrications and wife Ena Breaux; Kurt Fakier, owner of Louisiana Paint & Marine Supply and his wife, Cynthia; Andrew Soudelier, personnel manager at Cenac Towing and his wife Renee; James Hagen, manager of CTCO Shipyard of Louisiana; and Melvin Spinella, operations manager of Bayou Black Electric Supply and his wife, Elsie.

Sorting the Evidence

The FEC subpoenaed records of Whitney Bank, interviewed staff and also made its own inquiries of the purported contributors.

A resulting report, now part of the FEC file, details that the illegal contributions date back to communication between a local attorney – who is not accused of violating any laws – and the Landrieu campaign in 2007.

Terrebonne Parish attorney Berwick Duval was approached by the Louisiana finance director of Landrieu’s campaign at a fund-raising event in Houma. Duval has 12 relatives, the report notes, who have in the past contributed to Landrieu. Duval agreed to raise money for Landrieu’s campaign but had not completed the task by March 30, 2008, resulting in an inquiry from the campaign to Duval.

After an inquiry from the Landrieu committee, Duval communicated that he would pass contributions on shortly.

On April 24, according to the report, Cenac had arranged to obtain six cashier’s checks in return for one of his own instruments by calling an assistant manager at Whitney Bank in Houma. Cenac’s secretary arrived at the bank and gave the assistant manager written instructions and Cenac’s personal check in the amount of $25,300.

According to the report, the cashier’s checks were all made payable to “Friends of Mary Landrieu.” The instructions, the report says, listed the names of each person who was the remitter and the amount of each check.

On May 14, the Landrieu committee received a FedEx envelope containing six sequentially numbered cashier’s checks, according to the investigative report. The report says Duval raised the money from Cenac, whom it described as a “friend and client.”

Senatorial Invite

Subsequent investigation determined that there was no evidence of wrongdoing by Duval.

During the course of the investigation FEC personnel, upon interviewing bank employees, learned that in February 2008, Cenac used $15,000 of his corporation’s money to buy six cashier’s checks in the amount of $2,500 each, made out to “David Vitter for U.S. Senate.” Five of the checks listed people other than Cenac as the remitters.

According to the investigative report, Vitter personally invited Cenac to his campaign’s annual fundraiser in New Orleans, either in late 2007 or early 2008. On or about Feb. 4, 2008, Cenac bought the six checks from the bank.

The remitters named on the checks were Mr. and Mrs. Berwick Duval; Mr. and Mrs. Arlen Cenac Sr., who are Cenac’s parents; Mr. and Mrs. Kurt Fakier; Mr. and Mrs. Tim Solso; Chet Morrison and guest; and Cenac himself.

According to the report, Cenac has told investigators he is unskilled in election law and made the contributions in the mistaken belief that it was not improper to do so in the names of others.

The FEC and Cenac entered into a financial settlement agreement, as the FBI investigated criminal aspects of the case, which resulted in the U.S. Attorney’s Office bringing the current action.

Anna Christman, spokeswoman for Boente, said her ability to discuss details of the case is limited.

Questions that remain unanswered are what false statement Cenac is specifically accused of making, since he has is not a candidate for office, has filed no documents with the FEC other than responses to questions about the contributions – which the FEC acknowledges he answered – and made no other known statements to them.

On behalf of Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics, Sloan said she is pleased to see that the U.S. Attorney’s Office has chosen to enforce federal law, and that the FEC took the case as seriously as it did.

“We have laws, we are a nation of laws and everyone is expected to follow all of them, not just the ones they like,” Sloan said. “You can’t get around the law with the goal of influencing politicians. What this guy was doing was hiding the contributions. If you get caught, there are consequences.”