Golden Meadow-Fourchon Tarpon Rodeo succeeds in rebranding

July 8, 2015

Breaking: Port of Terrebonne loses appeal in case

July 8, 2015On East Main Street just before the Houma twin span, Leslie Price’s Confederate battle flag luffs, freely flies then luffs again on a day of variable southerly winds, high atop a pole beside a gate behind which a pit bull with toenails painted red, white and blue stands guard.

The alternative luffs and lifts are in themselves symbolic of how a nationwide battle over Confederate battle flags has ebbed and flowed over decades, with the most recent installment on the heels of a senseless and murderous event. But those who choose to display the flag maintain it is a symbol of heritage, not hate, and fail to see the reason for emotional response among those who find offensive and in some cases frightening. Those people fail to see how a legitimate claim can be made on behalf of a symbol of oppression and hate.

“I don’t hate anybody,” says Price, a former pipe-welder who was born in Houma, whose family has owned the property where his flag flies for generations. “I put my flag up because it is either that red white and blue flag or the other red white and blue flag, and I am from the South. It is a symbol of my heritage. It is not a racial thing. The Mason-Dixon Line was actually a country line. South of the Mason-Dixon Line was the South, South North America. It is where I was born, at Terrebonne General Medical Center, in Dixie. People are talking about taking down the flag, taking it away? They might as well take away our Zydeco music.”

Historians might balk at Price’s references. But for local black people the presence of his flag and others that appear more prevalent in the weeks following the mass killing of nine people in Charleston, allegedly the act of a hate-fueled 21-year-old drug abuser, the flags present a single message, no matter the stated motives of those who display them. The South Carolina legislature voted Monday to remove its Confederate flag from a memorial on the statehouse grounds.

Confederate battle flags were readily apparent on local highways this past weekend. At least two vehicles from whose beds people tailgated in preparation for Terrebonne Parish’s Independence Day fireworks displayed large rebel flags. At least four pickups were seen traveling local highways in the Houma area Saturday.

The battle flag itself never flew above Louisiana, and was never an official flag of the Confederacy, though the Southern Cross that is its most recognizable feature was part of the canton in some versions.

What a close examination of local history reveals is that some of the worst local transgressions against black people – short of widespread antebellum enslavement on sugar plantations – occurred after the war had ended. Local civil rights advocates say the effects of post-war subjugation are still felt today. But they also say the negative symbolism attributed to the flag is, for them, inescapable. If flags speak a language then a language’s key component – that its meaning be universal within a society – is not met by the Southern Cross.

“To me, that flag stands for slavery, racism and the bad things in our society that happened against African-Americans,” said Jerome Boykin, president of the Terrebonne Parish branch of the NAACP. While Boykin recognizes and respects Price’s right to fly any flag he wishes, the reasons why someone would insist on a display that offensive is beyond comprehension.

“That flag is a symbol of terrorism wherever it is and that flag is a symbol of our dehumanization during slavery,” said the Rev. Nelson Dan Taylor of Thibodaux’s Allen Chapel A.M.E. Church, who is also a civil rights attorney. “It is a symbol of the hostility we faced post-slavery. We find it difficult for someone to say they are proud of their heritage. It is a sheer insult to a large part of the population. What heritage are you trying to protect? The Germans have a hateful flag in their past but it is not a symbol of their pride. Is that flag expressing pride that you rebelled against a nation? Is it pride in ‘state’s rights,’ a combination of words that is awesomely horrible to black people? People tried to disrupt the United States of America. What pride do you have in that? It has tremendous power and it is an insult, and we wonder why people would want to insult in that way.”

No insult, Price still insists, is intended, when asked how he would respond to statements like those from Boykin and Taylor.

“I would tell them that stuff happened to everybody’s family,” said Price, who was also asked about the co-opting of any honorable meaning the flag may have once had by hate groups like the Ku Klux Klan. “A lot of people, they did take that flag and use for it other purposes. But that is not what that flag is meant for, it is meant for Southern pride and for Dixie.”

The removal of the rebel flag from the grounds of the South Carolina state house and removals of similar flags from places of honor in Alabama have raised the ire of groups like the Sons of Confederate Veterans, even as flag opponents say those removals have elevated the deaths of the nine victims in Charleston to martyrdom.

Flags, more than statues or monuments, are in most cases likely to raise either hackles or goose-bumps, notes Steven Knowlton, a University of Tennessee professor who is a vexillolologist, meaning one who studies flags.

“They are associated with such powerful institutions,” said Knowlton. “Very few people have strong feelings about the flag of their Cub Scout troop but the flag of a nation they have very strong feelings about, because of a nation’s power in your life.”

A complicating factor in current discussions about the battle flag is, according to Knowlton, that the “swirl of meanings people associate with a Confederate flag has changed over time.

“Many more white people now associate the Confederate flag with negative meanings than did 50 years ago,” said Knowlton. “It means all those things to different people but which people it means that to has changed. In Alabama when George Wallace was governor he had a different set of opinions as to what should be valued than the current governor does. It’s not to say that the flag in Alabama was meant to hurt anyone. If he sincerely believed at the time that white supremacy was good for all the citizens of Alabama then him erecting a Confederate flag was a sincere attempt for that to be taken at face value.”

Knowlton noted that despite the contrasting meanings people assign to the battle flag, differences of opinion are not unique to that ensign. The U.S. stars and stripes may in itself be an affront to Native Americans whose ancestors were mowed down by flag-bearing U.S. cavalry, and the Union Jack may be offensive to peoples who were subjugated by the British Empire.

If the rebel flag has such power then it was amply distributed when a white pickup with one flying on its right quarter – and a U.S. flag on its left – traveled up West Main Street, past black children riding bicycles near the Bayou Towers apartments, eventually making a left onto Hollywood Road, though neither they nor elders sitting on porches the driver passed appeared to pay notice.

What they likely didn’t know – along with most people in Terrebonne and Lafourche black or white, is that during a period after the war political opportunists, demagogues and outright racists largely ruled the sugar economies of Terrebonne and Lafourche – took tolls in lives and spirit, resonating in the opinions of some historians and advocates to the present day.

A network of white supremacists, a prominent Thibodaux judge among them, was at the center of travesties that included wholesale murders of black people in parishes near and distant, as well as the infamous Thibodaux Massacre, an event that caused blacks to flee the city, in many cases never to return.

Renowned historians have described the late 1870s and the late 1880s as a time when the region was on the cusp of a race war.

During those times and after, historians say, rebel flags were not needed to get the point across. Jerome Boykin says that as much as he finds the flag offensive, it is no more than symbolism.

“We can remove rebel flags from government offices but what we need to try to do goes further and deeper,” Boykin said. “It doesn’t change peoples’ minds.”

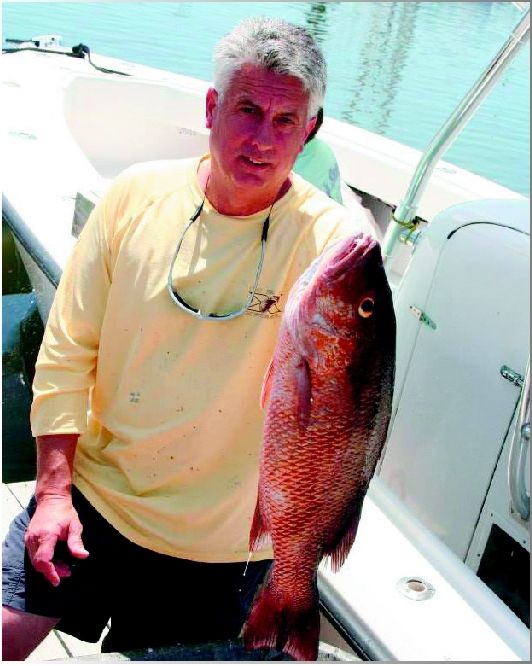

Jules Price (left), his brother Leslie Price and Linda Crochet, discuss the rebel flag outside their home on East Main Street in Houma. Crochet is holding a photo of her father Donald, who fought in WWII. The dog, a pit bull named Sissy, has red-white-and-blue painted toenails.