All-World Basketball: Locals thrive at International Tournament

March 21, 2017

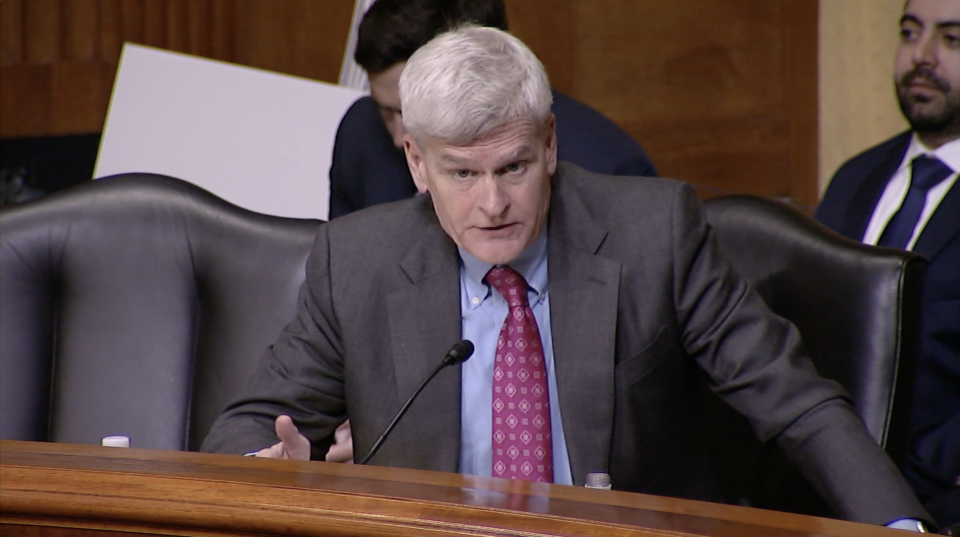

Locals announce run for Senate seat

March 21, 2017Attorneys representing Louisiana’s governor and attorney general continued presenting their defense Monday in a case that could radically change how judges are selected in Terrebonne Parish.

Political consultant Angele Romig, of GCR Inc., testified regarding her analysis of Louisiana elections from 1990 to the present, including judicial elections in Terrebonne Parish.

“Judicial incumbency is a key factor,” Romig said.

She also testified that financial assets and working ones’ base of support are also important for victory to occur.

While acknowledging that race is a factor, she said she did not focus on race in her analysis.

The trial was adjourned Monday evening until later this month because U.S. District Judge James Brady, who is hearing the case, must preside over another proceeding.

Counsel for the Terrebonne Parish NAACP presented their witnesses for 3 ½ days, relying on scholars and community members to bolster their claim that at-large election of all five Terrebonne Parish district court judges violates the Voting Rights Act of 1965 by diluting the votes of black electors parish-wide, precluding their ability to see a candidate of their choice ascend to the bench. The plaintiffs want the at-large scheme replaced, possibly by election of judges from five separate districts, with at least one drawn to encompass a majority of black voters. Creation of one sub-district with blacks in the majority is another option. Such sub-districts are the norm in many Louisiana parishes, due to prior cases based on the Voting Rights Act’s Section 2, which mandates that minority bloc-voting be mandated, under certain circumstances.

The defense began presenting their case Friday, St. Patrick’s Day, with Judge Brady clad in a green robe. A highlight of the testimony given by defense witnesses up to that point was during the appearance of 32nd Judicial District Judge David Arceneaux, who spoke of his personal reasons for opposing creation of an opportunity district, which he said is “philosophical.”

“It creates a district based on race,” Arceneaux said, under cross-examination by plaintiffs’ attorney Ronald Wilson. “In my opinion that institutionalizes racism … I just don’t want to see that happen in Terrebonne Parish.”

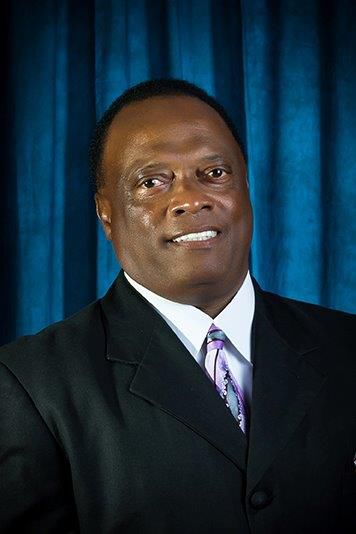

The first defense witness was Terrebonne’s first black judge, who was elected without opposition. That achievement, according to the state’s case, makes the NAACP claim moot.

“My goal is to be the best judge in Terrebonne Parish,” said Pickett, during a smooth direct examination in which he answered questions about his legal career, method of campaigning during an unopposed candidacy, and his commitment to equal treatment of people who appear before him.

The suggestion that a conspiracy of white Houma power brokers arranged for no white attorneys to run against him, leading to claims that he was “anointed” to be Terrebonne’s first black jurist, was rejected by Pickett, who also refuted any suggestion that his candidacy itself was a response to the lawsuit. He had made up his mind prior to filing of the NAACP suit in 2014, he said, and had considered running for the post in 2002.

He came under sharp questioning from attorney Ron Wilson, a member of the plaintiffs’ legal team with a long history of advocating for civil rights.

Pickett was unswerving in his answers to questions from Wilson about his party affiliations, which included registration as a Democrat, a Republican and finally independent with no party chosen.

“It was a choice,” Pickett said in response to each question about party affiliation. “It was just a personal choice.”

Wilson then switched to questions about Pickett’s relationship to retired Judge Timothy C. Ellender, in whose courtroom he had served as an assistant district attorney for 21 years, whose record of service during the trial has been defined by his suspension for appearing in a restaurant wearing blackface and a prisoner jumpsuit.

Pickett said he and Ellender were friends, but noted under further questioning that he had never visited the judge in his home. That Ellender was re-elected despite the offensive behavior is a key element of the case presented by Wilson and other members of the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund, who represent the plaintiffs.

Responding to a defense objection, Judge Brady cut off Wilson’s attempt to ask Pickett his take on how one of his acknowledged personal mentors, the late civil rights hero-attorney Oliver Hill, would view Ellender’s display.

Houma City Court Judge Matthew Hagen was the plaintiffs’ next witness. Although the city court bench is not at issue, the white Hagen’s defeat of black attorney Cheryl Carter, who finished last in a three-way race against Hagen and white attorney Randy Alfred.

Quizzed about the results, Hagen opined that Carter’s minimal war-chest may have played a role.

“She spent about $5,000,” said Hagen, whose overwhelming victory made a runoff election unnecessary.

The plaintiffs’ case was presented largely through reports from scholars in social science and history, who were subjected to fractious cross-examination by attorneys from the office of Attorney General Jeff Landry, as well as individual litigants who shared their personal histories of racial discrimination and attempts to have attorneys of their choice elected to the bench.

The last witness to appear on behalf of the plaintiffs was LSU undergraduate student Wendell Shelby-Wallace, who described “playing courtroom” as a boy with friends, usually ending up with the role of judge, and who as a student at Houma Junior High participated in a mock trial as a judge. He also described his feelings as a black student amid a white majority.

Terrebonne Parish, he said, was a great place to grow up in, in many respects.

“Good food and great people,” he said.

But then he described another experience, that of being a black student in a community where he is of the racial minority.

“I was not equal to my counterparts,” he said, despite a superlative school record and conduct predictive of promise. “You were not expected to achieve as highly and if you did it was as if you were not supposed to.”

Prior to Shelby-Wallace the plaintiffs had presented political history heavyweight Allan Jay Lichtman of American University in Washington, D.C.

On the stand for most of Thurday, Lichtman testified as to the long quest for change in Terrebonne Parish, matching up letters and other exhibits presented by plaintiff legal team leader Leah Aden with his own historical research on the matter. Under direct questioning by Aden, Lichtman testified he saw various attempts by Terrebonne officials, including judges, to thwart creation of a minority sub-district legislatively and an alleged change in the approach of local judges when it became apparent the sixth judgeship they once favored would involve seating a minority person as a judge.

Cross examination of Lichtman by Assistant Attorney General Angelique Freel was at times contentious, with the expert chafing at her question about how much he was paid for testimony in a 1994 Voting Rights Act case during which he testified.

“That’s completely insulting, and you know it,” Lichtman fumed, before stating that his fee was $400 per hour.

Asked by Freel how many minority judges are in Louisiana Lichtman balked.

“You can’t just look at the percentage of minority judges,” Lichtman said.

“Let’s look at how many minority judges there are in the real liberal states, like where you’re from,” Freel said, drawing an objection and a direction from Brady to rephrase the question.

She complied by then stating “states you think are less racist than Louisiana.”

—-

This story was reported by DeSantis and Caitie Burkes in Baton Rouge and written by DeSantis

(Burkes is a reporter for the Manship School News Service) ·