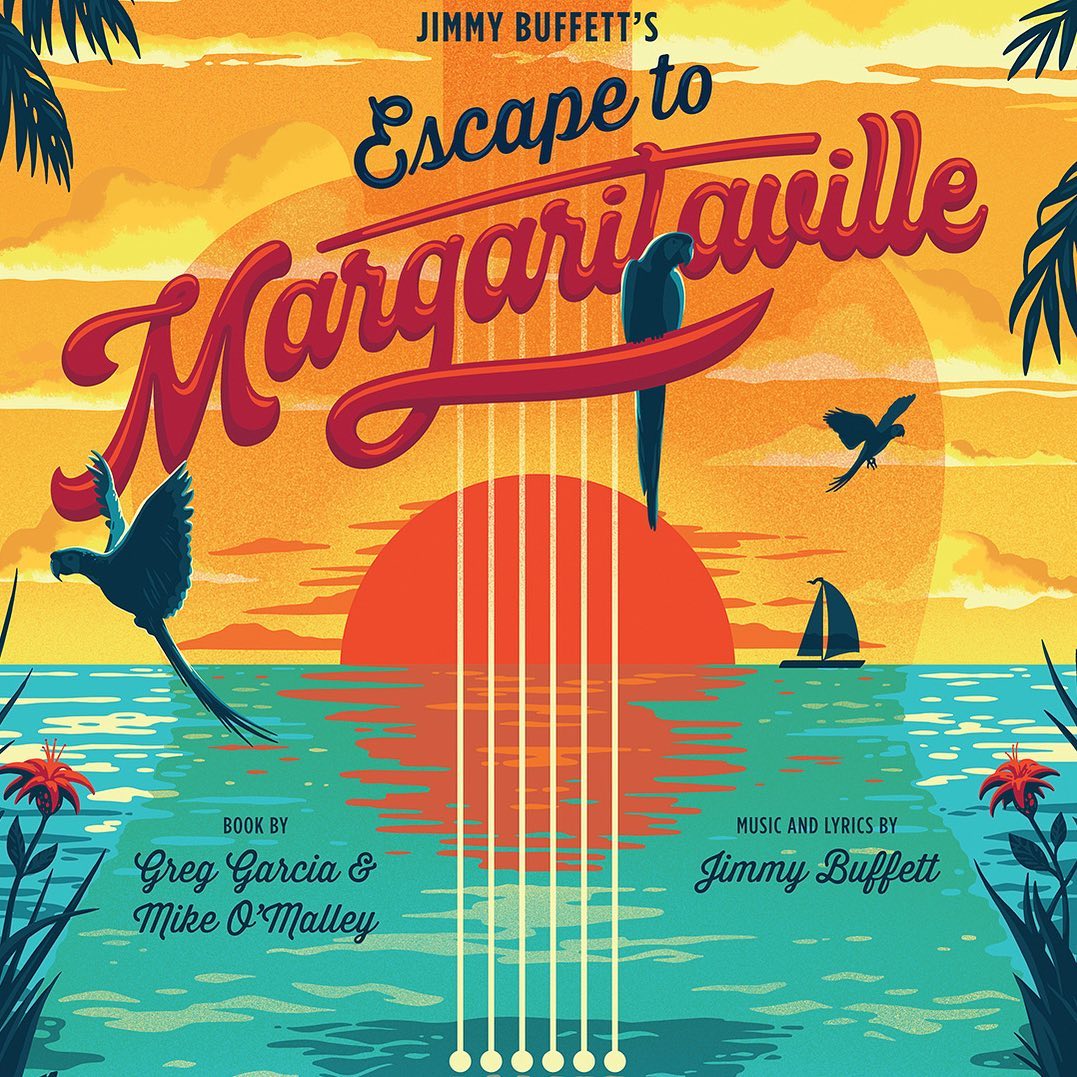

Auditions are open for “Jimmy Buffet’s Escape to Margaritaville” at Le Petit Theatre de Terrebonne

April 25, 2023

VCHS powerlifter Ben Ragas places 3rd at LHSAA State Championship

April 25, 2023By Claire Sullivan, LSU Manship School News Service

BATON ROUGE—The state’s near-total abortion ban has reignited efforts by lawmakers to address Louisiana’s low rankings in maternal and infant health.

One bill, authored by Sen. Beth Mizell, R-Franklinton, would establish a tax credit equal to half of the donations to pregnancy centers up to a total of $5 million. It would limit donations eligible for the tax credit to $5,000 per person.

The bill advanced through the Senate Committee on Revenue and Fiscal Affairs on Monday.

“We have talked for years about how low the rankings were in Louisiana on maternal wellness and health, and it’s not lost on me that I’m speaking to a bunch of men,” Mizell said to the 10 all-male members of the committee.

The pregnancy centers, called maternal wellness centers in the bill, provide services to pregnant women and new mothers including pregnancy confirmations, parenting classes, diapers and maternal and baby clothes. There are 36 of the centers in the state, Mizell said.

Though Louisiana has long had concerns over maternal and infant health, Mizell noted, the overturning of Roe v. Wade has added to them.

“That, in tandem with the ranking of the state, something had to be done to address it,” Mizell said.

Mizell’s bill is not the only one proposed by a Republican lawmaker to address a post-Roe Louisiana. House Bill 5, by Rep. Lawrence “Larry” Frieman, R-Abita Springs, cleared a committee last week and would allow mothers to recover half of out-of-pocket, pregnancy-related medical expenses from the father of a child.

Anti-abortion lawmakers around the country have been criticized for not caring enough about what happens to families forced to maintain unwanted pregnancies, and bills have been appearing to try to soften those complaints.

Mizell’s bill, like Frieman’s, drew support from anti-abortion activists. Benjamin Clapper, the executive director of Louisiana Right to Life, said the bill would be a “game changer” for pregnancy centers.

One woman, Kimberly Schultz, told the committee she could have benefited from such centers when she became pregnant at 14 and gave her baby up for adoption.

She said she now volunteers at a pregnancy center and has seen firsthand the benefit of these resources.

“They’re coming into these centers scared to death, and they don’t know what to do,” Schultz said.

But the bill also drew heavy criticism from abortion rights proponents. The proposed law says eligible centers must not refer women to or be connected with abortion clinics or “pro-abortion advertising.”

Michelle Erenberg, the executive director of Lift Louisiana, an abortion rights organization, said the bill would be “throwing away” $5 million a year that could be spent on other items.

She said that from 2011 to 2020, the state Department of Children and Family Services gave $11.3 million to crisis pregnancy centers—an investment she said did not improve maternal health outcomes.

She also questioned the legitimacy of the centers.

“They do not actually provide healthcare,” she said. “They’re not regulated.”

And, she said, most are not enrollment sites for Medicaid or the Women, Infants and Children Program, which provides nutritional support and other services to mothers and young children.

Under the requirements of the bill, the centers would have to provide a list of locations where pregnant women can apply for these services.

Erenberg suggested additional eligibility requirements, like making the centers become enrollment sites and prohibiting them from spreading inaccurate information about abortion or contraceptives or require clients to attend religious programs.

Angela Adkins, the executive director of 10,000 Women Louisiana, a progressive organization, opposed the bill but said that if the committee passed it, it should require that centers provide healthcare by licensed professionals.

Adkins, who formerly worked as the director of operations for the Baton Rouge Delta Clinic for abortions, also said she believes crisis pregnancy centers coerce women into giving their babies up for adoption.

Mizell pushed back hard against the criticism, calling the idea that the bill is throwing away money “disturbing.”

“If we don’t realize we’re on the same side, we’re never going to make things better,” she said.