Chance takes credit for auditor’s hire

May 2, 2012Tri-Parish Times turns 15

May 2, 2012Legislation intended to clean-up decades of on-shore contamination from oil and gas extraction could become stained with bureaucratic pollution according to one watchdog group.

Louisiana Law Abuse Watch Executive Director Melissa Landry said a bill addressing legacy lawsuits and passed last week by the state House of Representatives was accepted by both the oil industry and landowners.

Landry added, however, that substitute legislation, authored by state Sen. Bret Allain (R-Jeanerette), and being debated in the state Senate this week, could serve to prolong litigation. The result would be plaintiff attorneys remaining on the case and their client’s payroll longer, because of required oversight from multiple agencies.

“It is a complete bureaucratic quagmire,” Landry said after Senate Bill 731 went to committee on Friday.

SB-731 was filed as an alternative to House Bill 618, which passed 83-18 last Wednesday.

Authored by state Rep. Neil Abramson (D-New Orleans), HB-618 changes the process of deciding responsibility associated with property damages related to oil and gas production. If made law, cases could be settled by mitigation with enforcement oversight by the Department of Natural Resources Commission of Conservation before going to court.

The plan includes covering costs associated with admitting evidence related to subsequent lawsuits, filed by landowners against energy companies to whom property had been leased. Any decision would ultimately remain subject to a judge’s approval.

Lawyers for landowners complained that Abramson’s plan risks prejudicing a jury when it considers private damages that go beyond violation of state environmental regulations.

In an effort to appease those that questioned HB-618, Alain composed SB-731. “I asked the landowners what gave them heartburn about HB-618,” Allain said. “I wanted to find a compromise.”

According to Allain, landowners accepting HB-618 remained concerned that only the DNR commissioner was designated to make the ultimate decision in most cases. He said this group felt that too much power was being placed in one person’s hands.

“Landowners wanted more oversight,” Alain said. “So what I did was set up was an oversight committee comprised of the secretary of DNR, which is different from the commission of conservation, secretary of Department of Environmental Quality, secretary of Wildlife and Fisheries, commissioner of the Department of Agriculture, the Department of Health and Hospitals and, in costal parishes, the Coastal Protection and Regulation Authority. “

Allain said his bill instructs that commission to design reasonable plans when faced with state clean-up standard 29-b.

The strict definition of 29-b means no oversight is needed. “A lot of times in these cases a variance is given to be allowed to make it a more feasible plan,” Allain said. “Everything from changing a standard to not making them comply with certain parts of the standard.

“[Under HB-618] a $50 million cleanup could turn into a $1 million cleanup,” the state senator added. “The landowners fear that is what would happen without extended oversight.”

HB-618 allows a defendant to offer limited admission of responsibility. SB-731 adds that a required admission be made within 120 days of the landowner filing suit. The oil company’s remediation proposal would be submitted within 60 days after admission. In all, there would be a 240-day window between the civil complaint being made and a remediation plan being filed.

Sen. David Vitter was among the first responders to both pieces of legislation. He applauded the industry-backed HB-618 and called it a solution litigation that had lawsuits filed against every oil producer that ever used a given lease, even if only the initial company was to blame for environmental damages.

Vitter then called SB-731 a win for trial lawyers currently working on approximately 250 existing cases. “The Allain bill has unrealistic deadlines that will nearly ensure that a credible and admissible cleanup plan will not be developed in most future cases,” he said.

Vitter noted that delays in completing cases would only profit lawyers while keeping both landowners and oil companies from reaching their objectives.

“The two bills do look similar on the surface,” Louisiana Oil and Gas Association Vice President Gifford Briggs said. “But when you get down into it, subtle word changes have far reaching impact. It would be hard for the industry to agree with the [Allain] bill without amendments.”

Louisiana Landowners Association Executive Director Paul Frey said that Allain’s bill “needs a little work” but offers greater versatility to meet the concerns of oil producers, environmentalists and landowners.

“[SB-731] has a lot of concessions oil wanted and assurances for landowners,” Frey said. He insisted that involving several state departments would assure any possible concern being adequately represented when negotiating settlements on specific cases. “These agencies collaborate all the time. It is nothing new for them to work together to make sure everyone’s interests are protected.”

Frey said it is unfair to hold independent oil companies responsible if damages took place under a different lease ownership, but the process needs to focus on cleaning contaminated property as a bottom line.

“Actually, both these bills are very similar,” Abramson said after comparing his and Allain’s work.

“HB 618 is pretty straight forward and is supported by the business community and legal reform advocates,” Landry said.

“The purpose of the bill is it doesn’t resolve liability, but it puts the cleanup before litigation. The goal was to help get properties mediated more quickly.”

“I went one step further in my amendment,” Allain said. “I also included protection for independent oil producers.”

Allain said his measure protects independents from being held accountable for harm caused by another company possibly 50 or more years earlier.

“Small producers were getting it from both sides when they would have to pay for an original owner’s damage then try to sue for compensation from big companies,” Allain said. “So, my amendment says ‘OK major oil companies, whoever the responsible party is, you can admit to liability in this section of the law so you can get cleanup, but you cannot chase the next guy down the line if you caused the damage.’

“If you admit you are the responsible party, you buy it,” Allain continued. “I think that is a fair thing because it helps the independent guy still in Louisiana, trying to make money, invest in the field. The major oil companies sold these leases many years ago, but they are trying to stick the current [lease holders] with the bill. I just thought that was very unfair.”

“I can’t speak to their intentions, but I can say that if the goal is to expedite cleanup of these properties, adding five and possibly six other agencies into the approval process is not the way to accelerate an already broken system,” Landry said.

“I’m a landowner and have been working with the oil industry for 30 years, but I have no vested interest in [SB-731],” Allain said when asked if his bill carried personal benefits. “It was just the fair thing to do. I made a good faith attempt to listen to everybody and incorporate what would encompass everything. Neal Abramson’s bill is good. I just changed two things that made sense to me.”

“That’s what’s so hilarious about SB-731,” Landry said. “They are suggesting that it is a compromise bill and something everybody should be happy with. From the perspective of grass roots folks, for the pure purpose of working toward a solution to resolve litigation, I can’t imagine that the current version of SB-731 would help do that.”

Legacy lawsuits refer to cases where landowners claim oil producers using their properties left the areas polluted and contaminated. In turn, landowners sought financial compensation and state law required cleanup at the oil producer’s expense.

Companies responsible for the damage might be long gone or sold the lease to another company by the time a case was ready for argument, leaving the newest owner accountable for a previously occurring incident.

In some legacy lawsuits, landowners secured a cash win-fall beyond covering cleanup costs. Frey said that is not the issue at hand.

“Plaintiff’s attorneys have an agenda,” Frey said. “Oil and gas has an agenda. Landowners have an agenda. They all want it cleaned up.”

“It seems this Senate bill will ensure that legacy abuse will continue [by adding more contributors to the mix],” Landry said. “If the goal is to expedite the process and get our land cleaned up more quickly, it is clear the Senate bill is not the solution.”

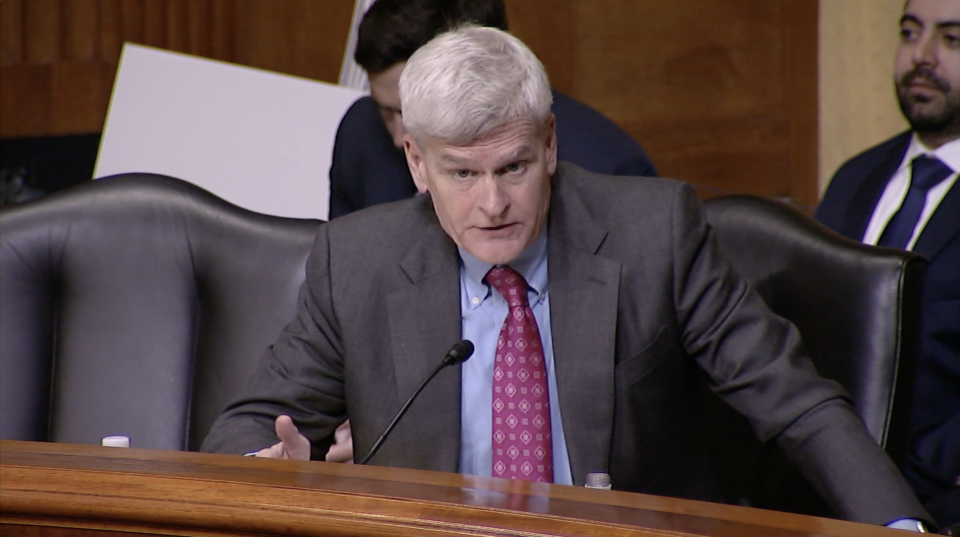

State Sen. Bret Allain contends he is speaking for all parties involved while presenting his alternative legislation to govern procedures in settling legacy lawsuits.