Thursday, July 7

July 7, 2011

Emma Hutchinson Huddlestun

July 11, 2011The panic has subsided, the Tiger dams removed and the spring flood threat is a threat no longer in Terrebonne Parish.

Evidence of the weeks-long preparation in response to heightened water detoured from the Mississippi River to the Atchafalaya Basin is scarce in Gibson, excluding some straggling sandbags and an approximately 5-foot high, 10-mile long levee constructed to protect structures south of Bayou Black Drive.

Richard Rhodes, a 44-year-old professional dog trainer who owns Teakwood Kennels south of Bayou Black Drive in Gibson, said the levee, despite not being challenged by floodwaters, was a “godsend.”

“They saved my business if we would have got the water,” Rhodes said. “For every hurricane that comes close to us, we get water. Last time, [after Hurricane Gustav], it was 18 inches of water in my kennels.”

Rhodes said Teakwood Kennels averages between $25,000 and $40,000 a year in profits, but when the area floods, he is forced to take a temporary leave. Where his business is located is prone to floodwaters, a persistent concern.

“It shuts me down, completely,” he said. “I’ve got to send everybody home. I come close to losing my house because I didn’t have no dogs in there. Baby needs shoes, so to speak.”

The levee built to protect from the spring flood threat stretches across the backside of Rhodes’ property and helped alleviate his flood concerns, but now he worries it is only temporary.

In the rush to provide emergency protection, the levee was constructed without the usual process of rights of way acquisitions. In order to make the levee permanent, the parish must acquire after-the-fact permits from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which includes environmental mitigation, and strike servitude agreements with property owners.

Terrebonne Parish President Michel Claudet said the parish “sorely” needs the levee.

“We’ve gotten preliminary indications that [the corps] would let us keep them up, certainly through storm season,” Claudet said. “If we would have to tear them down because they wouldn’t let us keep them up, then it would probably be after storm season and that’s what we’re trying to do.”

The corps sent a representative to the Terrebonne Parish levee board meeting in May to discuss plans of extending the Morganza-to-the-Gulf project 15.5 miles from Dularge in order to protect Gibson and western Terrebonne Parish.

The emergency levee could serve as a footprint for the Morganza extension, Claudet said. “Are they engineered the way we want them to be? Are they built the way we want them to be? Is the drainage, quite yet, where we want it to be? The answer to all of those is, ‘No, not yet.’ But is it a great start for us to get what we need, and the answer is, ‘Yes, it is,’ and I’d love to see where we can get it going,” he said.

Local and federal officials won’t have the only say in the levee’s fate. Once the state of emergency is lifted, property owners will be within their rights to deconstruct the portion of the levee that stretches across their property. Such a decision could weaken the entire system, and Rhodes said it would provoke a “lynch mob.”

Claudet said he would prefer anyone who was thinking about deconstructing the levee to first contact the government complex.

“We’d be very disappointed if they did so without consulting with us, or at least contacting us, but we’re hopefully going to be able to work with each and every one of them to try to allay any complaints that they have,” Claudet said.

Some of the tasks the parish will take on to make the levees more “livable” for homeowners, Claudet said, include providing access to the back-end of the property, culverts and other drainage-related improvements.

“I’d like for them to leave it alone,” Rhodes said. “If they’re going to come back in, yeah, make it right. Clean it up, level it off, whatever they’ve got to do and make it to where it can withstand some water coming in.

“It might not be great. It may not be perfect. But it’s the best we’ve got until they can come out here and do it right.”

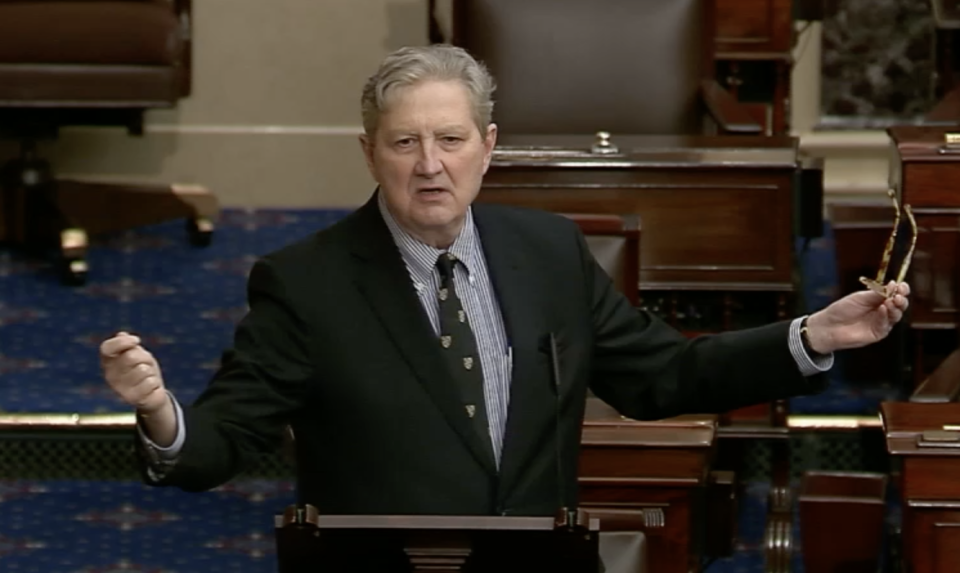

Richard Rhodes stands in front of an emergency levee constructed earlier this year in preparation for the backwater flood threat. Rhodes wants the levee to remain in its current form. ERIC BESSON