Theotine "Theo" Ulysse Dardar

June 23, 2009

Diana Benoit Toms

June 25, 2009With little fanfare, Amy Hebert was sentenced Thursday to two consecutive life sentences for brutally murdering her 9-year-old daughter Camille and 7-year-old son Braxton inside their Mathews home Aug. 20, 2007.

Wearing the blue garb of Louisiana Corrections Institute for Women inmates, Hebert sat in silence as defense attorneys Richard Goorley and George Parnham made a final appeal for a new trial, arguing it was impossible for the 42-year-old former school paraprofessional to receive an impartial trial.

After nearly two weeks of testimony in May, it took a 12-person jury less than three hours to find Hebert guilty of bludgeoning her children with several kitchen knives in the early morning hours. Experts said on the stand that the children each had more than 50 stab wounds – many piercing their bodies.

After hearing additional testimony, including tearful statements from the children’s father and Hebert’s family, only nine of the 12 jurors voted in favor of sentencing her to the death penalty. Instead, in accordance with state law, District Judge Jerome Barbera issued the consecutive sentences.

The lesser sentence, however, drew objections from Goorley and Parnham.

“I have one question,” Goorley said from the Lafourche Parish Courthouse steps shortly after the vedict was rendered. “How do you serve a life sentence after you’re dead? Having her serve two consecutive life sentences doesn’t serve a purpose, but it looks good on paper.”

Lafourche Parish District Attorney Cam Morvant sees it differently, however.

He said the sentences were appropriate based on the heinousness of the crime and the pending appeal.

“I wanted to be prepared in case something happens with one of the counts,” Morvant said. “If one gets reversed, it still means she has to serve out a life sentence for the other (murder).”

Were a governor ever to commute Hebert’s sentence, the district attorney said she would still be facing a second life sentence. “I think that’s appropriate based on the horrible acts that she did,” he added.

As Lafourche Parish deputies escorted Hebert back to prison, her case was turned over to the Louisiana Appellate Project, thus ending the legal dealings for the time being.

David versus Goliath

The Hebert trial pitted Morvant, who had never tried a capital case in his 26 years as a Lafourche attorney, against Goorley and Marty Stroud, both of the Capital Assistance Project of Louisiana, and Parnham.

Goorley’s recent connection to the Tri-parishes dates back to last September, when he defended serial killer Ronald Dominique, who pleaded guilty to murders in Terrebonne and Lafourche parishes. Parnham was thrust into the spotlight when he unsuccessfully defended Houston mom Andrea Yates, who was found guilty of drowning her five children in the bathtub in her house.

Yates’ defense, much like Hebert’s, focused on severe depression and psychosis. In preparation of Hebert’s trial, Morvant made several calls and trips to Houston to review court transcripts from the Yates trial and speak directly with prosecutors who argued the case.

The local investigation and trial, which cost Lafourche Parish taxpayers close to $100,000, makes Hebert’s case the most expensive trial the district attorney has tried. With the appeal still pending, the final tally is still unknown.

For their part, Goorley and Parnham flew in experts to testify that Hebert suffered from severe depression for years and, on the morning she arose to an imagined voice ordering her to kill her sleeping children by repeatedly stabbing them, was psychotic.

Morvant, on the other hand, relied on the testimony of three experts of his own, who painted Hebert as in control of her actions the days leading up to the murders.

“A lot of capital cases cost substantially more than what this case cost,” Morvant said. “I’ve heard of some reaching $500,000, and that’s not including the appeal process. Regardless, this was money well spent.”

Well spent, he reasons, because of the crimes themselves.

‘It had to be the death penalty based on what she did’

According to state law, the murders of Camille and Braxton warranted first-degree murder charges by definition, Morvant explained.

“It had to be the death penalty based on what she did,” he said. “She killed more than one person under the age of 12. That meets at least two of the criteria for first-degree murder.”

But the atrociousness of the crime shook local law enforcement authorities to the core.

Responding to a “well-being call” from the children’s father and Hebert’s ex-husband, Chad Hebert, deputies walked into a bloody scene Aug. 20, 2007.

The children’s paternal grandfather, R.J. “Buck” Hebert, told jurors of finding his former daughter-in-law in the bloody master bedroom after he climbed inside a utility room window.

“Oh God, help,” a deputy at the scene remembered hearing Buck Hebert cry out. The off-duty officer would be the first lawman to uncover the horrific murder scene.

Following a blood trail to the master bedroom, deputies found Hebert lying in bed with her deceased children at either side. On the bed, 11 kitchen knives – including an electrical knife – were recovered. As deputies pulled the covers from the bed to retrieve the children’s bodies, the body of the family dog, also stabbed multiple times, fell to the floor.

In court, Morvant played video captured from the Taser, in which Hebert is seen holding a knife and threatening authorities to leave the residence. It would be the only time jurors would hear Hebert speak throughout the two-week trial.

On the video, Hebert was visibly bleeding from self-inflicted stab wounds to her wrists, chest and neck. In all, Parnham said his client had more than 30 wounds.

“The plan was for her to commit suicide in the ultimate act of revenge against her ex-husband,” Morvant said in his closing argument. “It all fell apart and that’s why we’re here.”

Based on forensic psychologist Dr. Glenn Wolfner Ahava’s testimony, the defense theorized that Hebert heard psychotic hallucinations ordering her to kill herself and the children to prevent her ex-husband from gaining custody of the children. Ahava spent more than 70 hours interviewing Hebert and conducting a battery of tests to determine if she was falsifying psychotic symptoms.

Hebert told Ahava she stabbed Camille first while her brother Braxton slept nearby. Hebert said she followed her daughter to the master bathroom where she repeatedly stabbed her.

A Jefferson Parish assistant coroner testified Camille had more than 30 stab wounds in her torso and another 30 to her scalp, while Braxton had more than 30 wounds to the front of his body and an additional 20 to 25 puncture wounds in his back.

Both children had defensive wounds on their arms where they had tried to prevent Hebert from stabbing them, the coroner said.

Photographs from the crime scene continue to haunt jurors to this day.

“They died a slow and painful death,” Ahava said from the stand. And as she plunged the knife into her daughter, the child begged for her life.

“Mommy, I love you. I don’t want to die,” Hebert recalled her daughter saying, Ahava testified. Hebert replied, “I love you too, but (the children’s father Chad Hebert) is coming to get you and we have to be together,” the psychiatrist recounted.

Hebert reportedly told Dr. Alexandra Phillips, a psychiatrist at Ochsner St. Anne General Hospital in Raceland where she was originally medically treated in the days following the murders, that “Satan was in the room laughing at her,” the doctor testified.

Defense witness Dr. Phillip Resnick, an Ohio-based psychiatrist, told jurors that Hebert suffered from eight of the nine indicators for someone suffering from major depression with psychotic features.

Based on her reasoning abilities at the time of the murder, Resnick said Hebert “killed out of love, not hate. She psychologically believed the children were better off in heaven. Her deposed, distorted thinking made her unable to rationally weigh if the homicide was right or wrong.”

Forensic psychiatrist Raphael Salcedo countered for the prosecution, arguing that although she may have been depressed the days before the murders, Hebert did know right from wrong the morning of Aug. 20, 2007.

Case turns on suicide notes

Jurors later agreed that the psychiatric evidence was less telling than two vitriolic suicide notes penned by Hebert that detectives found at the scene.

In his closing argument, Morvant said Hebert harbored anger at her ex-husband for allegedly having an affair prior to the couple’s divorce in 2005. Shortly before the murders, Chad Hebert announced plans to marry the woman he was reportedly seeing, Kimberly Mendoza.

The two have since married.

But a lack of the children’s blood on the notes contradicted Hebert’s claim that she had written the notes after the children were dead.

Morvant argued that it was the angry tone of Hebert’s missives to her ex-husband and former mother-in-law that best demonstrated her intentions the morning of Aug. 20, 2007.

“You are telling me that you want to move on with your life, go ahead, but you are not getting the kids, too,” Hebert wrote.

At one point, Hebert suggested her ex-husband use the monies collected from selling the house and the children’s life insurance policies to “buy some more” children, Morvant noted, displaying the note on a courtroom wall.

“That is not the note of a psychotic, delusional person,” he told jurors. “That is someone with rage and anger who wants to hurt someone.”

The jury ultimately sided with Morvant, returning a guilty verdict in less than an hour.

But sentencing the Mathews woman to die for killing Camille and Braxton Hebert would prove a more daunting task.

‘The jury had to decide’

From the outset, it was Morvant’s intention to have a jury decide if Hebert should live or die for killing her children.

“I went over her mental issues and I was personally satisfied that she was not legally insane at the time she committed the crimes,” he said. It was only then, six months after the murders, that Morvant filed motions seeking the death penalty.

“The jury had to determine whether she got the death penalty or life in prison. That’s how the system works,” he explained. “Deciding whether someone gets life or death is a lot different than whether someone is guilty or not. The death penalty is a lot more personal.”

After nearly eight months of preparation, including several mock trials, Morvant’s team was ready.

The prosecution called two people – Chad Hebert and his mother Judy Hebert – to speak to the impact Camille and Braxton Hebert’s short lives had had on them.

“They were my angels and they meant the world to me,” Chad Hebert said, struggling to maintain composure as he addressed the jury. “People ask me how I make it from day to day. I say I have a range of emotions that no one will ever be able to imagine.

“I can see photos of them and it just tears my heart out,” Chad Hebert told the jury. “Then, I laugh sometimes when I remember the little things that make them special.

“There’s not a day that goes by that I don’t cry,” he added.

Chad Hebert admitted he had not viewed the crime scene photos. No one had to show him photographs to make clear the pain and fear his children endured in their final moments.

“No one can imagine what they went through,” the tearful father said. “I have experienced emotions from one end to the other. But I know I have to get up and continue because that’s what they would have wanted.”

Chad Hebert’s mother, Judy, sobbed as she spoke of her grandchildren playing doors down from her.

She’s since sold her St. Anthony Street home to escape the memory.

“When God sends you children, he sends you joy,” Judy Hebert said during the penalty phase of her former daughter-in-law’s trial. “But when God sends you grandchildren, he sends you a blessing. They’re your heart. And right now, I have a hole in my heart that will never be filled.”

Amy Hebert’s father, Daniel Talbot, took the stand to beg the jury to show his daughter mercy.

“I would like to take her home right now,” he told the jury. “She doesn’t deserve this. She was too good of a person. I never dreamed that this would have happened.”

Over the course of the penalty phase and several times throughout the trial, witnesses recalled Hebert’s excellent parenting skills. Even Chad Hebert said prior to Aug. 20, 2007, he considered his former wife and the mother of his two children to be beyond reproach as a parent.

“She is the nicest person you want to be around,” her neighbor Mary “Bonnie” Morris said from the witness stand. “She has a big heart most of all. She is full in her faith and would give her shirt off her back if you needed it.”

Even a prison guard with the state’s women’s correctional institute spoke on Hebert’s behalf, suggesting she could help other inmates with Bible studies.

In the end, three members of the 12-person jury refused Morvant’s request to sentence Hebert to death for murdering her children.

No one will ever be the same

In the weeks leading up to Thursday’s sentencing, jurors, attorneys and family and friends have been slowly returning to post-trial life.

Chad Hebert’s family maintained their silence about the case, but a Web site posted at www.hebertmemorial.com continues to display photographs and memories of young Camille and Braxton.

As Amy Hebert adjusts to prison life, the district attorney responsible for putting her there is readying for his second capital murder case: Billy Daigle, who is accused of running down a Lafourche Parish sheriff’s deputy.

“(The Hebert trial) was an emotionally, physically grueling and draining process,” he said. “It was every day. We put in 14 to 16 hours a day on this case.

“I still think about it,” he added. “I had to look at those (crime scene) photos off and on for a year and a half.”

Morvant would show those photos of the children’s bodies to jurors only once, knowing the impact it would forever have.

“I knew it would have an impact on some of them,” he said. “I know what impact it had on me.”

Gheens resident Sheila Toups, 57, who sat on the jury, said she hopes to never be called again for a capital murder case.

“It was very upsetting,” she said. “It is something I will never, ever forget.”

For those closest to Amy Hebert, the unimaginable events of Aug. 20, 2007, remain a mystery.

Ann Tabary, a longtime friend of Hebert’s, recalls standing in for the Mathews woman when she married Chad Hebert and visiting after Camille and Braxton were born.

The two friends continue to talk by phone and Tabary visited Hebert when she was being held in Lafourche Parish. She has vowed to stand by Hebert in the years ahead.

“I am so blessed that God has placed her in my life,” she said. “Her friendship means the world to me.

“I am praying and looking forward to the day when I will be a witness to her testimony, which she will share with the world,” she added.

Tabery isn’t alone.

Stacey Stegmann, a friend and fellow member at Victory of Life Church where Hebert and her children worshipped, said the Mathews woman continues to have an impact on others.

“She has a way of touching people’s lives in ways I have never experienced,” Stegmann said. “Most times, she never says a word. It’s the presence and peace of God that she carries. It beams from her. Her heart is always wishing to please God first.”

In memory of the children

Playgrounds were erected at Lockport Upper Elementary School where Camille Hebert attended the fourth grade. A similar facility bearing the banner “Braxton’s Buddies” was built at Lockport Lower Elementary where her brother attended the fourth grade.

Chad Hebert also created scholarships to benefit students majoring in education in each of his children’s names.

From the witness stand, he talked of his daughter’s compassion and love for her brother. She enjoyed singing, dancing and sharing time with friends and family, according to Chad Hebert’s memorial site.

Braxton, who often sported a “cheesy smile” in photographs, loved Thomas the Train, cars, water sports, being tickled and being with his sister.

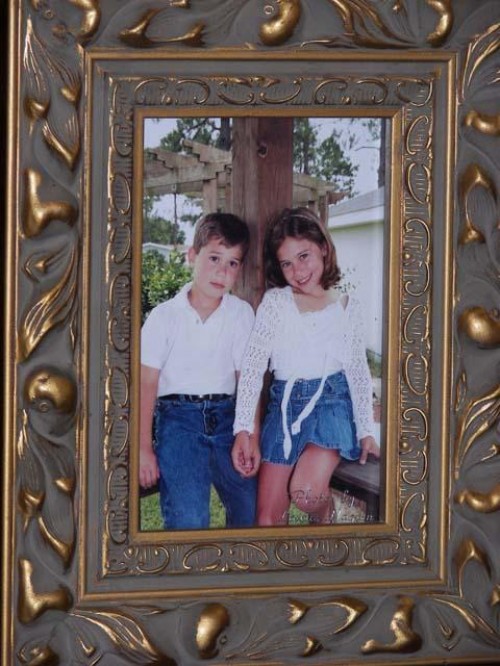

A framed pictures shows Camille and Braxton in the days before they were killed by their mother, 42-year-old Amy Hebert. Their father, Chad Hebert, has formed the Camille Catherine and Braxton John Hebert Memorial Scholarship at Nicholls State University in his children’s honor. * File photo / Tri-Parish Times