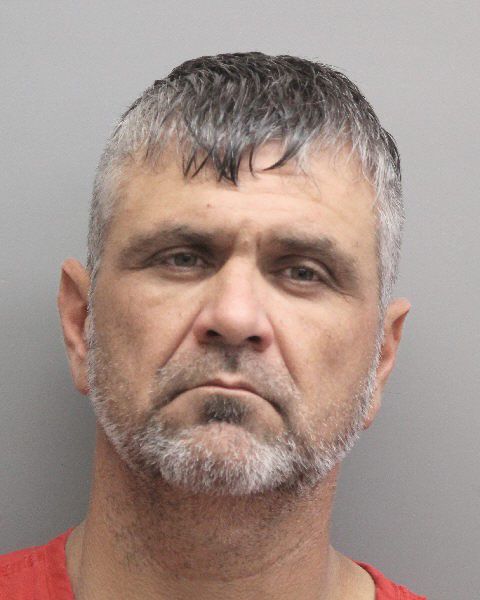

BREAKING: Suspect in custody after chase in south Lafourche

October 17, 2017

Suspect charged with attempted murder in Lafourche high-speed chase, standoff

October 18, 2017Danielle Brocato and Keisha Tanner spent some time at BP’s Houma Operations Learning Center last week.

Brocato and Tanner were not there to take any classes, though. Instead they were hoping to inspire the next generation to follow their career paths.

Brocato and Tanner were featured speakers at last week’s “Females Fueling the Workforce” event, a two-day gathering of local high school students and women working in the oil and gas industry. Each of them gave high school sophomores and seniors insights into how they ended up in the energy sector and what they do in their jobs.

Brocato talked about how she went from wanting to become an actress to developing a love for history while in college. She spent time working at a law firm before deciding she did not want to be a lawyer. Eventually she followed her father’s path into the oil and gas industry to her current position at Chevron as a “land man,” someone who procures land leases for oil and gas exploration.

Tanner spoke about her own confusion about her future career when she was a college student. After originally struggling at The Georgia Institute of Technology, Tanner refocused a challenge from a faculty member and zeroed in on her desire to become an engineer. These days she is an engineer for BP with more than two decades’ worth of experience.

“Females Fueling the Workforce” is in its fourth year and was originally an offshoot of the Work It! Louisiana campaign started by outgoing South Central Industrial Association Executive Director Jane Arnette 15 years ago. Arnette said the Work It campaign was designed around building awareness in the need local industry jobs and promoting workforce development for those positions. Arnette said data showed that only 20 percent of local high school students went to college, and the industry needed to reach the remaining 80 percent to meet their employment needs.

“We needed to address those people. My standard thing in making these presentations is number one: we want to grow our own workforce. Number two: we want to bring integrity back to the student and nobility back to the workforce,” Arnette said.

The woman-specific campaign has since been passed onto Nicol Blanchard, Fletcher’s interim executive director of institutional advancement and the coordinator of Females Fueling campaign for the last two years. Blanchard said the event bused in an expected 1,300 girls from 16 high schools in the Bayou Region and River Parishes. Arnette said the event has the same goal as Work It, which is awareness.

“Women need to know, it’s okay, you can become an engineer. It’s not a guy thing,” Arnette said. “They need to get away from this, it’s a guy thing. It’s not a guy thing. You can become an engineer. You can become a truck driver, a CDL.”

Blanchard said the program not only raises awareness but also promotes female empowerment for the young girls attending. She said that Females Fueling can have future benefits to companies and women who end up entirely separated from the energy sector.

“It’s about showing these girls women in the energy industry and showing them what’s possible. Even if they don’t work in oil and gas, maybe they’ll think, if they can do that, I can do something else I want to,” Blanchard said.

Events like those at the Learning Center last week may be critical to the local region’s ability to cut into the local wage gap, where women earn substantially less than men in both Terrebonne and Lafourche Parishes, where the wage gap is even larger than it is in Louisiana, one of the highest states in the country. According to United States Census data, women in Terrebonne working full-time, year-round jobs in 2015 (the most recent year of available data) earned a median wage of $29,255 a gap of about $22,250 from the $51,505 median wage for men. In Lafourche, the median wage for a woman in 2015 was $31,622 for a gap of $21,343 from the $52,965 wage for men.

Put another way, a woman earned about 57 percent of a man’s earning in Terrebonne Parish in 2015. In Lafourche the median woman’s wage was about 60 percent of a man’s in 2015. Both those numbers are behind the state gap of about 66 percent, based on Census data, and well behind the 80 percent nationwide figure reported by the National Partnership for Women and Families.

The wage gap has stayed consistent over the last five recorded years, as well. From 2011 to 2015, Terrebonne’s gap hovered between a low of 56.2 cents a woman earned for every dollar a man earned and a high of 57.8 cents, recorded in 2011. Over the same time period in Lafourche, the lowest figure was 57.7 cents in 2012 and a high of 59.9 cents in 2014.

The good news for women is that median wages for women increased with each additional level of education in both parishes. In Terrebonne circa 2015, women with less than a high school diploma would make $16,487 in median wages. The median wage for a woman with some college or an associate’s degree was $26,166, while women with a graduate or professional degrees earned $51,021. That year in Lafourche, women without a high school diploma earned $14,295 on median. Some college or an associate’s degree brought a wage of $25,654, and a graduate or professional degree brought a wage of $51,627.

Men’s wages do not have that same linear path based on education. The median wage for a Terrebonne Parish man with a high school degree in 2015 was $49,403, considerably higher than the $43,654 a man with some college or an associate’s degree earned. In Lafourche that year, those figures were nearly identical with male high school graduates and those with some college or an associate’s each earning almost $52,000. In both parishes in 2015, men with graduate or professional degrees earned the most, with Terrebonne men earning $68,798 and Lafourche men earning $70,526.

The bad news for women is that they have to attain much more education, costing both money and time, to earn wages of men with less education. A woman with a bachelor’s degree earned about $1,500 less than a man with a high school diploma in Terrebonne in 2015. That year in Lafourche, a woman with a bachelor’s degree was about $11,500 behind a man who had only finished high school. The gap still persisted at the top of the education ladder, as well, with women earning about $18,000 and $19,000 in Terrebonne and Lafourche, respectively, to their male counterparts with graduate and professional degrees.

That difference can partly be explained by the preponderance of men working in local industry, labor-intensive jobs which provide some of the highest pay in the area but that many times do not require education beyond associate’s degrees. Construction and extraction jobs make up almost 9,000 jobs across both parishes and are at least 96 percent male in each. Installation and maintenance jobs are both around 96 percent, while production operations employ about 8,700 and are 88 percent male in Terrebonne and 91 percent male in Lafourche. Transportation jobs are another 5,500 jobs and are 83 percent male in Terrebonne and 91 percent male in Lafourche.

Katherine Gilbert-Theriot, director of business retention and expansion for the Terrebonne Economic Development Authority, highlighted events like Females Fueling as critical to showing girls successful women in those male-dominated fields. Gilbert-Theriot said those events can bring to light the challenges women face in those fields but also the rewards they can reap by bucking the trend. Gilbert-Theriot said opening up women to more career possibilities needs to coincide with companies fostering a culture that empowers and compensates women more equitably, as well.

“I think that’s an ongoing conversation definitely within companies. Allowing the environment to be one where women and their accomplishments are valued and celebrated and paid equitably, that’s something the private sector really is going to have to address really one company at a time. Just finding ways to find that intrinsic value that women bring to the company, and those skillsets and look to how they can pay them a little more equitably.”

Both Brocato and Tanner cited the values of their companies in valuing their perspectives and addressing the wage gap. Brocato said she was not familiar with statewide wage gap data, but that she did not sense one with her employer.

“I know that I get paid very well, as well as my co-workers, and I believe we’re all on the same scale there. So I don’t think there is a wage gap in Chevron,” Brocato said.

Tanner said that as an engineer she can still enter a room and be the only “other” in a male-dominated field. She said part of the value of the increase of diversity in career fields is the different perspectives that are brought into conversations and can offer different lenses to help find solutions to problems. She cited BP’s commitment to respect as one of its core values that gives her the space to have conversations that create better understandings among coworkers of different backgrounds.

“It creates the expectation that we try to understand one another. And with that value that I hold very dear, it has allowed me to have those open and honest conversations that create space not only for myself but for others,” Tanner said.

Critics of studies on the wage gap cite things such as career choices for individuals as large contributors to the wage gap. Vicki Shabo, vice president of the National Partnership for Women and Families, said that even after accounting for those factors, national data shows women are still paid less than men.

“Across the country, if you look at every industry, every occupation, basically every job category, women who work full-time year-round are paid less than men,” Shabo said. “National data and many studies have concluded that it isn’t job choice, it isn’t education, it isn’t most of the factors that you can point to that explain all of the difference. That once you control for all of the relevant factors, there’s still close to about 40 percent of the difference that can’t be explained. That could be conscious or unconscious bias or discrimination.”

Shabo cited policy efforts across the nation to enable women to stay and advance in the workforce while encouraging men to take on more caregiving responsibilities. She said policies like key family medical leave, fair scheduling and pregnancy accommodation laws as well as paid sick days and investments in child care from employers could eat into the wage gap. Shabo said while such policies carry an upfront cost for employers, they reap the benefits of happier employees, who are generally more productive and more likely to stay with their employer when returning to the workforce after having a child or caring for a family member. If the policies create higher wages for women, it would mean a more robust local economy, which benefits all employers and the community at large, according to Shabo.

Gilbert-Theriot said the TEDA board has not adopted any resolution calling for support of local efforts in the state legislature to address the wage gap, saying that issue has a scope larger than the local agency.

“I am sure that the board and TEDA do want to see women paid equitably fairly for their work contributions, but there’s no been policy adopted or resolution or stance adopted by the board,” Gilbert-Theriot said. “It’s not something that’s been really discussed as a policy, because I think it’s a lot bigger than our local agency.”

The National Partnership’s 2017 report on Louisiana’s wage gap highlighted its effects on working women. According to the report, if the gap were eliminated a woman could pay for nearly 39 more months of child care or about two years’ worth of food for her family or almost 20 more months of rent each year. Shabo said there is strong support for closing the wage gap, but solutions too often get mired in partisan disagreement.

“This is having tangible impacts on what people are able to provide for themselves and their families now and affects their ability to save for the future,” Shabo said.