Odomes’ lifelong friend to testify against him

August 25, 2011

Georgia Lou Rice

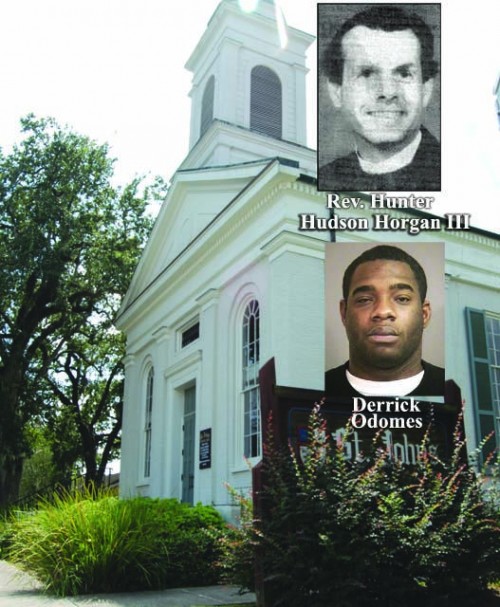

August 29, 2011A panel of 12 jurors convicted Derrick Odomes of second-degree murder of the Rev. Hunter Horgan III, a Thibodaux priest who was found dead in a church rectory 19 years ago.

The jury reached a unanimous decision in about 90 minutes Thursday afternoon. Odomes sat slouched at the defense table with his left index finger on his temple and his thumb under his chin as District Judge John E. LeBlanc’s clerk read the decision.

Sentencing is set for Sept. 23 at 11 a.m. LeBlanc ruled during pre-trial proceedings that Odomes, now 33, could not serve past his 21st birthday if found guilty of the murder due to the state’s juvenile protection laws in 1992.

Odomes was 14 at the time of the crime.

LeBlanc sentenced Odomes to life in prison last week after the 17th Judicial District judge ruled him to be a habitual offender with six felony convictions since 1995.

“Whatever the sentence is, we have a sense of justice,” said John Perry, Horgan’s cousin and the family’s spokesperson. “We have closure.

“(Lafourche District Attorney Cam Morvant) deserves a tremendous amount of credit. He promised us four years ago he would try to bring us closure. He is a man of his word, and we are so grateful for that.”

LeBlanc instructed the jury that it should render a guilty verdict if 10 or more jurors believe beyond a reasonable doubt that Odomes murdered Horgan with a specific intent to kill or inflict great bodily harm.

The judge also informed the jury it could convict Odomes of manslaughter or negligent homicide. Manslaughter is murder that arises out of “sudden passion, caused by provocation,” and negligent homicide requires a “gross disregard in the interests of others” that exceeds behavior from a reasonable person.

The six-male and six-female jury heard about 10 hours of testimony, evidence and lawyers’ comments. The verdict was rendered within an hour and a half.

“We tried the case to bring closure to the family,” said Morvant, who added that he had been questioned about the need for a murder trial after Odomes was given a life sentence.

“You give your evidence and you give it your best and then it’s for the jury to decide,” Lynden Burton, Odomes’ attorney, said.

Burton, based in New Iberia, said he has already filed an appeal against the habitual offender sentence. It is unknown if he will appeal Thursday’s second-degree murder conviction.

The state presented two pieces of forensic evidence that tied Odomes to St. John Episcopal Church rectory, where Horgan’s body was found with blunt- and sharp-force wounds on Aug. 13, 1992.

A bloody fingerprint was recovered from a table near Horgan’s body, and a thumbprint was found on the cold-water knob to the kitchen sink. Two fingerprint analysts with the State Police Crime Lab testified that the prints matched Odomes’.

A trail of blood led from the business office, where the minister’s body was found, through a hallway, a meeting room and into the kitchen, where diluted blood was discovered in the sink.

Patrick Lane, a crime scene investigator with the state police crime lab, testified the bloody print was transferred to the table when the blood was still wet. Investigators were unable to prove the blood came from Horgan’s body.

The Louisiana State Police Crime Lab, which handled the evidence, did not conduct DNA tests in 1992.

More than a decade later n the prints were not positively matched until 2007 n too much time had elapsed, there wasn’t a large enough sample size and a coloration test on the blood prevented the state from being able to glean a DNA sample from the print, about the shape of a “dime,” Lane said.

“If we would have had it, you would have seen it,” Morvant told the jury during his closing argument. “This is not TV. We don’t get to sit down with the police and write the script.”

Derrick Reed, the state’s final witness, said Odomes told him that he had killed Horgan. Reed also said he saw a pair of cream-colored pants with blood on the front of each leg when he was helping Odomes’ mother move belongings out of her shed shortly after Hurricane Andrew. He said Odomes threw the pants in the garbage.

Reed said he and Odomes were friends and “grew up together.”

Reed is currently serving a 10-year sentence with the state Department of Corrections for aggravated battery. He appeared before the jury with his hands and feet shackled, wearing blue jeans and a faded-blue prisoner’s shirt.

Morvant asked the jury to “hold the defendant accountable” and “bring the family closure” by using its “good, God-given common sense.” “Don’t leave it at the doorway,” he said.

Burton made a passionate closing argument on his client’s behalf, hammering away at the state’s lack of evidence.

Investigators lifted 33 sets of fingerprints from the rectory and Horgan’s 1990 Toyota Camry, which was found less than a mile from the church on St. Charles Street the night of the crime. Only two prints matched Odomes’.

Fingerprints were crosschecked with suspects, an FBI database and elimination sets, which are provided by people who had previous access to a crime scene.

Several sets of prints, the fingerprint analysts testified under cross-examination, did not match Odomes, the database or the elimination sets.

Included in the sets of prints that did not have a match, Burton emphasized, were two prints retrieved inside on the rectory’s front door, a print on the bi-fold closet door in the rectory’s business office, and several prints lifted from the Camry.

“You’re not leaving common sense at the door,” Burton told the jury. “You’re seeing the forensic evidence that we do have.”

In the trial’s climatic moment, Odomes took the witness stand Thursday morning in an effort to refute a statement he made to detectives in 1998. In the statement, which was presented to the jury on Wednesday, Odomes said he had never been inside the church rectory.

As a child, Odomes, frequented the playground behind the church rectory many times, he testified. He also said he entered the rectory to use the restroom and drink water and spoke to Horgan on more than one occasion.

Odomes said he was unsure the last time he entered the rectory before the homicide, saying it could have been “days, months or weeks.”

He was “scared” to admit this to detectives during the 1998 interrogation, he said, because of the way he was approached, “as if they came to hurt me.”

During a tense exchange with Morvant during cross-examination, Odomes said the manner in which detectives approached him during the initial interview was “just like the circus you’re putting on now.”

“It’s not a circus,” Morvant quickly responded. “You might think it’s a circus, but this is a murder trial.”

Whether or not Odomes had ever been in the rectory was critical to the state’s case because of the forensic evidence that linked him to the rectory.

“I was glad (Odomes testified),” Morvant said. “It’s a shame he never owned up to what he did. I think the jury saw through what he tried to do.”

Cross-examination of the defendant also gave Morvant the avenue he needed to present the jury with Odomes’ felonious history.

Odomes, who has been convicted of six felonies since 1995, was sentenced to life in prison without the benefit of suspension or parole one week ago when LeBlanc ruled he was a habitual offender. The state’s habitual offender statute mandates a sentence between 20 years and life for someone convicted of four or more felonies.

LeBlanc ruled Odomes’ criminal history off-limits before the trial, so his background was not discussed before the jury until the cross-examination.

Odomes feigned forgetting the circumstances of his previous convictions, asking Morvant to provide the dates of each conviction before he admitted under oath to each one. The subtle strategy illustrated to the jury that his earliest conviction was in 1995, three years after Horgan was murdered.

From the witness stand, the alleged killer also contradicted everything Reed said. The confession and the setting in which Reed claims he saw the bloodstained pant were lies, Odomes said.

On the stand, Odomes was combative at times, denied killing Horgan as Morvant accused him in front of the jury, and denied “having a recollection of telling (Reed) that.”

Perry, the Horgan family’s spokesman, said they can “respect” whatever sentence LeBlanc imposes because “we have closure.”

“Hunter was a tremendous person,” Perry said. “It has been 19 years. He didn’t get to see his son graduate college, become a man, become a father, and the same thing with his daughter. It was a senseless murder.”

Ed. note: For complete, in-depth coverage of the Derrick Odomes murder trial and the events preceding it, pick up a copy of Wednesday’s Tri-Parish Times.