Jindal budget gaps appear in legislative review

April 1, 2015

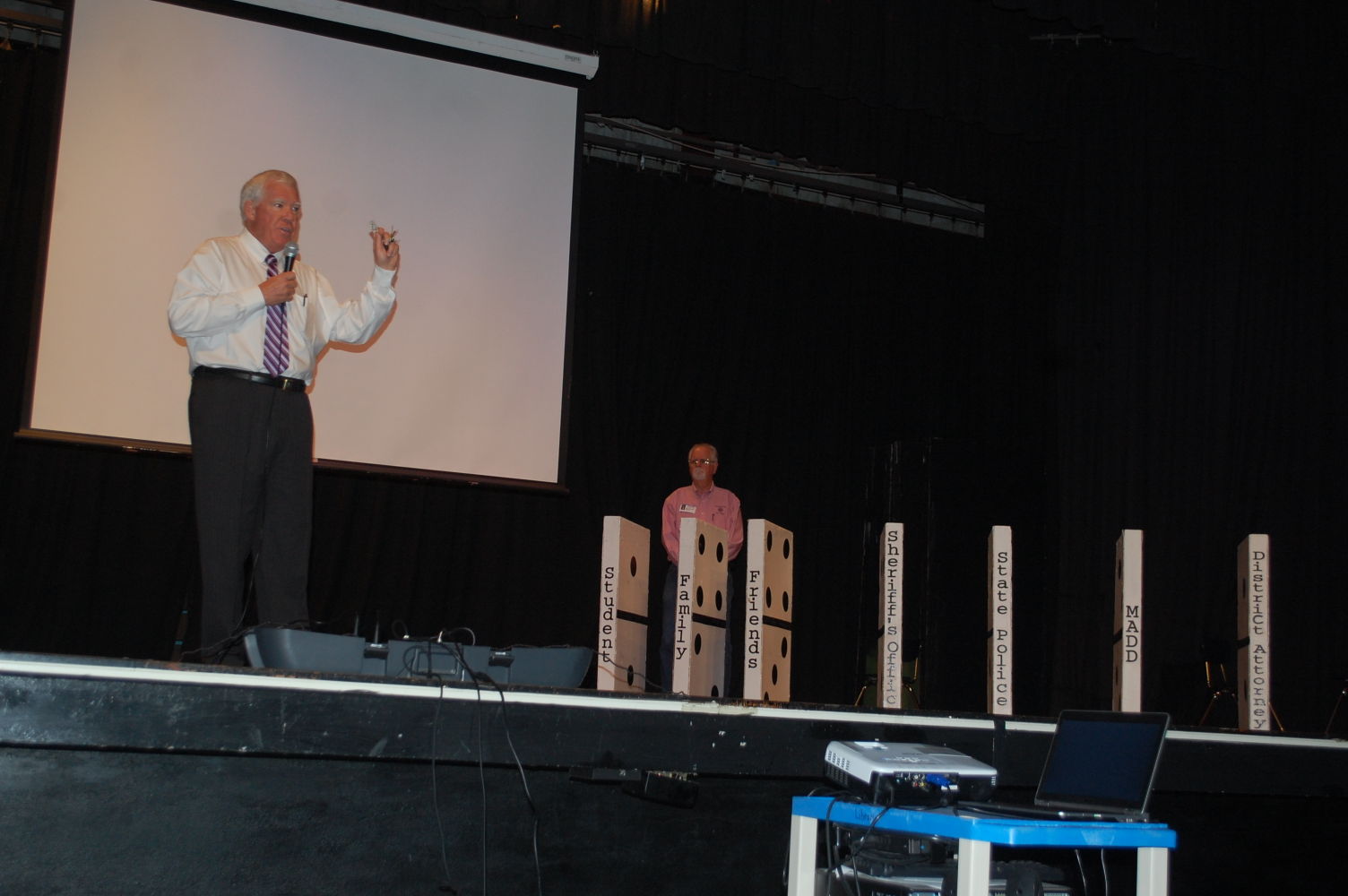

Lafourche students cautioned on the ‘Domino Effect’

April 1, 2015In the serenity down Bayou Terrebonne, love was unspoken, but understood.

That is at least by Samuel Dardar Sr., a Pointe-aux-Chenes native who quietly trapped, hunted and fished every day and sometimes into the nights to provide for his family of 15 children and wife, Nazia.

“Even though it rained, he still went out there and did it,” said JoAnna Plaisance, Samuel’s 14th child. “Even though it was cold, freezing, he still went out and did it. Even though it was hot, he’s still out there and did it. And then, there was no air conditioning in the boat!”

Samuel lived and raised his children in much the same way as his ancestors have for hundreds of years. Samuel was a Chitimacha American Indian.

In his youth, he was rascally. The road on the Lafourche side of Bayou Terrebonne was more of a trail through woods in the 1940s, a perfect place to set traps for passersby.

“They had nothing to do, so they found things to do,” said Theresa Dardar, Samuel’s daughter-in-law. “That was one of them. Be mischievous. ”

In 1949, Pointe-aux-Chenes was a community secluded from the sprawling industrialization of southeast Louisiana. There were many miles between it and the Gulf of Mexico, and roads were nothing more than dirt walking paths surrounded by oak and cypress trees.

“It looks like night and day compared to what it looked like before,” said Nazia Dardar, who solely speaks Cajun French. Her daughter JoAnna served as her interpreter. “Before, it was a whole bunch of trees and now, you’ve got little bit trees here and there and then the water now is at your back door and before it was far; it was mostly all land.”

That was when Nazia Naquin met the love of her life, Samuel, whom she’d marry and bear 15 children. They would go on to bear 40 grandchildren and 80 great-grandchildren.

Nazia, who was 14 at the time, met Samuel through his sister. Samuel, then 17, lived on the Lafourche side of the bayou, and Nazia lived on the Terrebonne side.

“He’d cross in a pirogue to go visit with [me],” Nazia said. She said Samuel’s good looks attracted her to the love affair, which would last a lifetime.

Samuel was fishing and trapping around the time they met, traditions that he would pass on to his children, who still practice them today.

“My daddy was quiet,” JoAnna said. “He was a quiet man.”

Samuel didn’t talk much, demonstrating a stoic demeanor toward his offspring as well as his approach to life.

Son Donald Dardar recalls one particular instance that would have warranted emotion.

“I was young and I stepped in the gallon of paint and I dumped it,” Donald said. Samuel didn’t get upset or fuss at Donald.

Donald said his father taught him everything he knows. Today, the son is the second chairman of the tribal council for the Pointe-au-Chien tribe.

“Even though he wasn’t telling us that he loved us, we knew he loved us,” JoAnna said. She said she could tell by “the way he looked at us.”

Samuel would take his children out of school every winter to a camp in Bayou Perot, near Lafitte, to trap. There, he taught his children to catch, skin and dry game on wooden molds.

”I really didn’t learn too much in school, but I was learning the trades of my dad, and to me it was important,” Donald said. “Really important.”

Donald still fishes, hunts, and traps as a way of life to this day.

Over the course of his life, Samuel saw the landscape around him change dramatically. Saltwater intrusion has killed many of the oak trees for which Pointe-aux-Chenes was named, leaving behind the skeletons of once-great timber. Erosion has led to water covering what used to be land.

“Now you go out there and it’s all lakes,” JoAnna said. “We’ve never seen land like he’s seen because it kept getting covered up.”

But Samuel adapted, keeping a mental map of navigable waterways, always remembering where the water was too shallow for a boat.

It was on that boat that he taught his children from an early age to fish. Donald still remembers crabbing with his father.

For JoAnna, the memories come in the morning when, as a young girl, she’d see her father off from the dock – unless she was joining him.

JoAnna still pictures her father, “standing in the cabin, holding his steering wheel, pulling his shifter to shift the boat, and taking off down the bayou.”

May the mariner enjoy safe travels and bountiful catches.

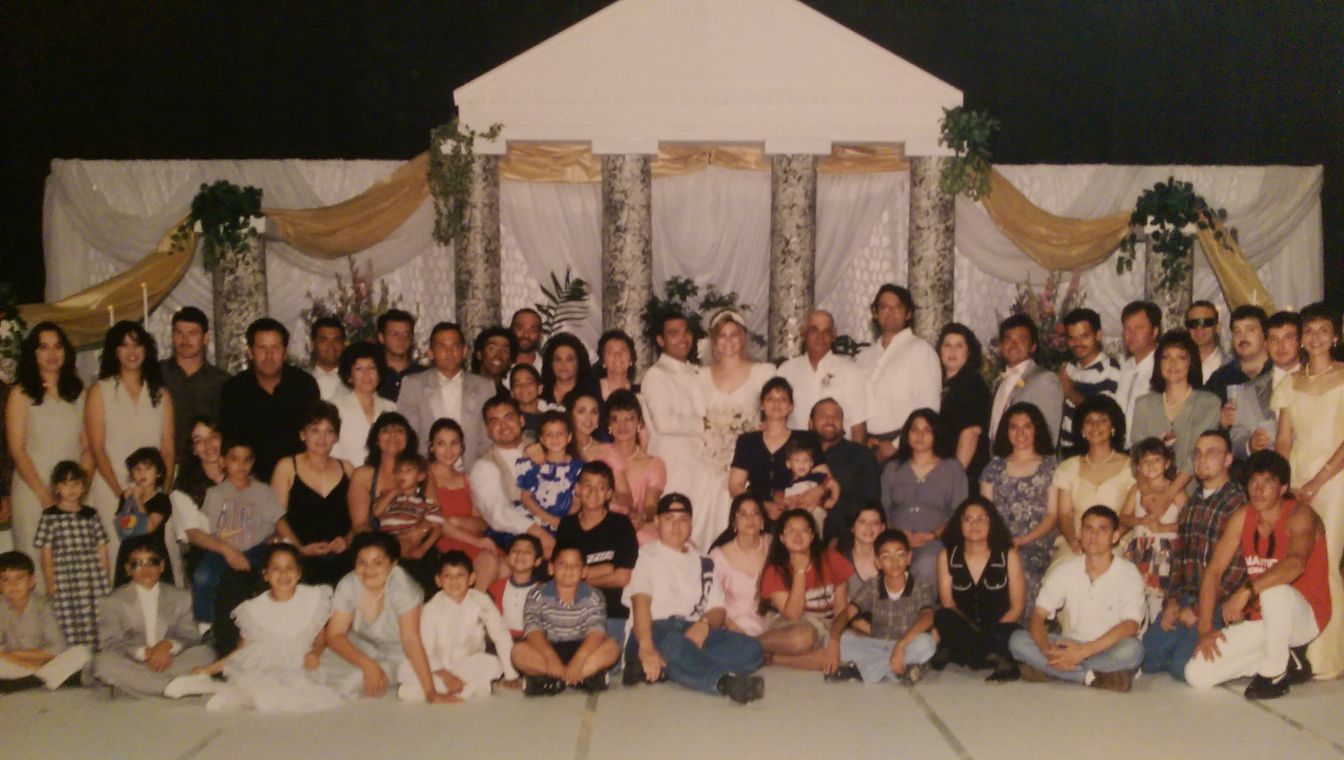

Samuel Dardar (bottom, right) poses with his family in this portrait. Samuel trapped and fished to provide for his large family all his life, continuing the Native American tradition of living off of the land in the Bayou Country.