Willie W. Bonvillain

November 20, 2013

Patterson still alive after hard-fought victory

November 27, 2013Seven score and 10 years ago, two great armies gathered at the sleepy Pennsylvania town of Gettysburg and fought a three-day battle that turned the tide of the War Between the States.

For Erik Himmel of Schriever, this year’s commemorations of the battle – and of the famed address given by President Abraham Lincoln – have personal significance.

While Lincoln was dedicating a proper burial ground for federal soldiers – four months after the battle and as war still raged – Capt. Victor St. Martin, a son of Ascension Parish, lay in a shallow battlefield grave, like so many other Gettysburg Confederates.

Erik Himmel is St. Martin’s great-great grandson, and his quest to find the slain captain’s final resting place took nearly 30 years.

“He died as they charged up Cemetery Hill in the dusk,” Himmel said of his ancestor. “He was killed as he was attacking, by cannon or musket fire, I’m not sure.”

The St. Martin family of Ascension Parish was well-established in 1861, and already had a brush with history on other shores. Patriarch Joseph St. Martin had served as personal surgeon to Napoleon. That year – which began with Louisiana’s secession – saw the enlistment of Victor St. Martin into Company K of the 8th Louisiana, an element of the famed “Louisiana Fighting Tigers,” along with his younger brother Emile.

Initially called the “Phoenix Rifles,” the outfit was made up primarily of farmers and some planters from Ascension and Assumption parishes.

They trained at Camp Moore near Kentwood; Victor was a 1st Lieutenant and Emile 1st Corporal. Victor, then 33, had six children and another on the way. Among the 8th Louisiana’s senior officers was a colonel named RT Nicholls, a future Louisiana governor for whom the university in Thibodaux would be named.

BLOODY MARCHES

Victor’s military career is documented and maintained in family histories. He remained in Louisiana during early 1862 recruiting volunteers, then joined the troops during the bloody Shenandoah Valley campaign in Virginia under Gen. Stonewall Jackson. In June of 1862 came a promotion to captain and leadership of the company, and he fought at the second Battle of Bull Run. He also was involved with the Maryland campaigns, a fact that would become important to Erik Himmel more than a century later. Engagements at Harpers Ferry and Antietam followed; It was there, on Sept. 17, that Victor was grievously wounded.

Captured by federals, he was later exchanged and by Nov. 5 was back with the company. As 1862 melded into 1863 there was more fighting for Victor at Chancellorsville, where Jackson was killed and Nicholls lost his foot, removing him from the battlefield. Then came the massing of armies north and south in 1863 north of the Mason-Dixon Line, in Gettysburg.

CARRIED TO THE REAR

The first day – July 1 – involved sporadic fighting at first, according to historical accounts.

By the evening of July 2nd Company K was among those ordered to engage in a diversionary tactic as part of a broader effort to remove big Union guns and seize a spot with a commanding view of the battlefield, called Cemetery Hill.

Gettysburg historian and lecturer Scott Mingus, in his book “The Louisiana Tigers in the Gettysburg Campaign” (LSU Press, 2009) gives detailed descriptions of the 8th Louisiana’s involvement.

According to his accounts and others, the Tigers used smoke and darkness to cloak their attack on the Union guns.

It is likely, according to circumstances and a requested assessment from Mingus, that Capt. Victor St. Martin’s last act of bravery occurred as he and others attacked artillery of the 1st New York battery.

The fighting, which began with a charge of Tigers giving rebel yells, was described as fierce hand-to-hand combat.

The fighting was described by Union Capt. R. Bruce Rickett of the Pennsylvania artillery, who wrote that, “at about 8 p.m. a heavy column of the enemy charged on my battery, and succeeded in capturing and spiking my left piece. The cannoneers fought them hand to hand with handspikes, rammers, and pistols, and succeeded in checking them for a moment, when a part of the Second Army Corps charged in and drove them back. During the charge I expended every round of canister in the battery, and then fired case shot without the fuses. The enemy suffered severely.”

At some point in the fighting one of those who suffered was St. Martin.

“Comrades carried Capt. Victor St. Martin to the rear, he would soon die,” Mingus’ book states.

“Details of St. Martin’s death are not fully known. Not many of the Tigers left written records of the assault,” Mingus wrote last week in response to an e-mail query. “My best estimate is that he was most likely wounded in the firefight near Weidrich’s New York battery. That’s about as far as the Tigers got, and they began to fall back under rather heavy pressure from Union reinforcements, specifically my three great-great-uncles’ brigade. They were in the 7th West Virginia, which was among the counter-attackers.”

DEATH AND DISHONOR

The battle ended two days later, on July 4. It is likely at that point that St. Martin was buried, and that Emile, who survived the fighting, either might have aided the burial or noted its location. St. Martin might have been buried in a rapidly dug battlefield grave, either separately or with other members of his unit.

An individual grave was much more likely for an officer, said Caroline Janney, an associate professor of history at Purdue University who has written and lectured widely on Gettysburg and in particular how the monumental task of dealing with the dead was handled.

“With officers they were more detailed,” Janney said in a telephone interview. “There were some descriptions left of the burial sites, someone else in the company might have written home and said we buried the captain in a certain location.”

Initially both Union and Confederate dead were buried unceremoniously.

“They would have been in mass graves, often buried according to where they had fallen on the field,” said Janney. “If they died in a corps hospital they might have been grouped together. Most were in unmarked, usually mass graves.”

Immediately following the battle the sights and smells were horrendous. One soldier, quoted in the blog the National Park Service, which maintains the battlefield, wrote that on July 4th the carnage was “simply indescribable-corpses swollen to twice their size, asunder with the pressure of gases and vapors…The odors were nauseating, and so deadly that in a short time we all sickened and were lying with our mouths close to the ground, most of us vomiting profusely.”

A PRESIDENT SPEAKS

Lincoln’s speech at Gettysburg was brief, at a gathering dedicating the new cemetery for Union casualties on the battlefield.

“The federal government saw Confederates as rebels and treasonous,” Janney explained. “The thinking was why should they belong in cemeteries with people who were fighting to preserve the Union.”

Identification and re-burying of the Union dead was in progress when Lincoln related how “Four score and seven years ago our forefathers brought forth on this continent a new nation, conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.”

As burial of Union force continued even well after Lincoln’s address, the Confederates remained in their shallow trenches, and their treatment was – by all accounts – equal in no way to that afforded their counterparts in blue.

In the years that followed the war, treatment of Confederate dead was a sore spot with many southerners.

“The treatment of the dead was something they were very aware of,” Janney said. “The way you treated the dead was a reflection of how you thought about the living. Former Confederates for their part were very much questioning and distraught about their place in the nation when they lost the war. How the federal government did or did not honor their dead was reflective of how they would be treated in this nation, and they saw it as dishonor for their part.”

According to accounts from the park and other ample documentation, rescue of Confederate remains commenced in 1871, by the Wake County N.C. Ladies Memorial Association. Other groups got involved, and more than 3,000 soldiers were moved to Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond.

Other Confederate dead were shipped to cemeteries in the Carolinas and Georgia.

CONTINUING QUEST

In Schriever, more than 100 years after those first burial efforts, Erik Himmel began attempts to learn more about his great-great grandfather.

The family had some information, though it was scant. He did learn that relics, including a button, had been sent to family members but were later lost.

He did locate a “visitor’s card” with St. Martin’s photograph on it, a picture he determined was taken in Baltimore based on its markings.

Relatives at some point had known where the captain was buried, but the information did not get carried through the generations.

“I suspect that it was Victor’s brother Emile who actually removed the buttons and removed his sash,” Himmel said. “There was another piece a personal article that was sent and supposedly an artillery dagger but that is in the possession of a family member in Texas as far as I know.”

Information on St. Martin’s resting place remained elusive.

“I am going to say almost 75 years they just lost track of him. It wasn’t passed on to the next generation,” said Himmel, who continued making inquiries.

“I contacted Gettysburg first and they referred me to Hollywood cemetery in Richmond,” Himmel said. But Hollywood was a dead end. A check of the roster of Gettysburg dead revealed no mention of St. Martin. He might just as well have been in some shallow grave at Gettysburg – not all the Confederate dead were removed – but there were still no clues.

CONFEDERATE HILL

Based on information Himmel supplied, including what he knew of the photograph, someone in Richmond in 2006 put him in touch with Mike Williams, the Baltimore of a handyman service and commander of the Maryland Society of the Military Order of Stars and Bars and also the Col. Harry W. Gilmor CQ Camp of the Sons of Confederate Veterans. Some of the dead from Gettysburg were buried at a Baltimore cemetery, in an area called Confederate Hill and Williams made inquiries.

“I had this information about Confederate Hill and Erik thought that Victor St. Martin might perhaps have been brought to Baltimore,” said Williams, who went through the Confederate Hill roster.

“Then I thought let’s take a longshot and I called the receptionist at Green Mount Cemetery and asked if she would go through her cards and lo and behold she found him.”

The discovery that Capt. St. Martin was buried at Green Mount, the space noted by a very small stone marker, moved Williams to tears.

“There is something about not knowing where your ancestor is and you can’t account for his body for years,” he said in a telephone interview Sunday, voice breaking. According to information Williams was able to gather, Emile St. Martin was able to arrange with friends in Baltimore for the burial plot to be donated.

For Himmel, the news was overwhelming, and met with joy, although he is humble about his perseverance.

“It is a piece of the family puzzle that I have been able to just re-fit into the picture,” Himmel said.

Duties as a pilot for Halliburton prevented Himmel from attending a special ceremony in 2009, when Williams and other members of his groups honored St. Martin with a headstone issued by the US government noting his Confederate service.

Williams said Confederate honors were attended to, with descendants of other soldiers there dressed in period costumes.

HONORED AT LAST

The federal government began issuing headstones for Confederates 1906, under limited circumstances. Today the process is more widely practiced, although strict requirements were enacted concerning verification of an ancestor’s service.

As for the treatment of Confederate dead at Gettysburg, Erik Himmel has no strong opinions.

And as he continues to seek information about his ancestor, Himmel notes that it is interest in family, rather than specifically in the war, that drives him.

And if he could speak with his great-great-grandfather today, what would Himmel ask him?

“The list of questions is unending,” Himmel said. “But I would like to know about his family life, even before the Civil War. What was the local lifestyle they had? What drove him and others from Bayou Lafourche who joined up? Why did they march off and what kind of conditions did they have to bear?”

Asked what he would wish to tell his ancestor – other than perhaps break the news that the cause he fought for failed – Himmel paused before giving a brief answer.

“I would tell him that after the war his descendants have done well,” he said. “And we didn’t do anything to embarrass him.”

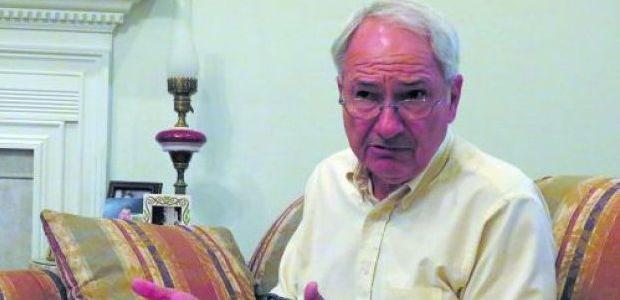

Erik Himmel displays a replica of the pistol his great-great grandfather, Capt. Victor St. Martin, might have carried at Gettysburg, along with memorabilia he has collected.