Violation risk for snapper anglers

April 7, 2015

Deepwater Horizon’s effects still being tallied 5 years after the spill

April 7, 2015Louisiana shrimp fishermen are at risk of getting caught in the crossfire between state and federal fishery regulators in a war of words dating back more than 50 years.

But interviews with federal and state officials confirm – despite Louisiana’s official claims to the contrary – that state waters only extend currently to three miles from shore, and that beyond those three miles federal rules govern those who fish for a living.

An official handbook for shrimp fishermen published by the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries, which cost taxpayers more than $20,000 to produce, doesn’t make that clear. Phone calls for clarification to that agency by fishermen have also resulted in the communication of incorrect information.

The state’s official 2014-15 booklet of shrimp rules and regulations incorrectly identifies the Louisiana boundary to be “inland waters and out to nine nautical miles.”

Asked for clarification, LDWF spokesman Rene LeBretton noted that the Louisiana Wildlife and Fisheries Commission took action to “extend Louisiana state waters from three miles offshore to three marine leagues, or approximately 9 nautical miles, offshore.”

Interviews with regulators both state and federal, as well as a review of relevant court decisions going back more than 50 years, reveal that the Commission has no such authority, and that only a court or Congress would have the authority to do so.

LeBreton issued a statement Friday which states the agency encourages fishermen to use caution and their own personal judgment when fishing beyond the three-mile boundary that is currently also recognized as federal waters, as it is fully expected that federal agents will continue to enforce federal law.”

“Until the U.S. Congress confirms Louisiana’s action, the battle will continue over Louisiana’s state water boundary,” the statement reads. “Shrimpers should be aware that shrimp regulations do differ between state and federal waters.”

In other words, shrimpers fishing beyond Louisiana’s traditional three-mile state limit should expect the Coast Guard or NOAA Fisheries agents to take action against them if they do not have a federally required shrimp permit.

Dularge fisherman Chester Herring is among local fishermen who thought the state pamphlet gave them license to not have the federal license.

“I read the pamphlet, and by reading that book that is exactly what that tells me, it is black and white,” said Herring, who is in the midst of preparing his 42-foot boat, Keep’Em Comin’, for the Louisiana’s upcoming shrimp season.

To be on the safe side Herring called LDWF.

“They told me it was a gray area,” Herring said.

Other shrimpers – especially those with bigger boats that routinely travel offshore waters – say they haven’t taken any chances.

Kimberly and David Chauvin, who operate the Bluewater Shrimp and David Chauvin Seafood companies in Dulac have three vessels that routinely fish Gulf of Mexico waters and all three have federal permits.

She hopes fishermen who may have experienced confusion will now be mindful of the regulations.

Failure of boat owners to follow the permit requirements, Chauvin said, could result in increased enforcement actions and regulations overall, that will affect law-abiding shrimpers as well as others.

Federal authorities contacted by The Times make clear that shrimp fishermen must have the highly-prized federal permit if they venture beyond three miles.

“Any vessels more than three miles offshore need a federal permit,” said Allison Garrett, a spokeswoman for NOAA, which regulates fisheries.

As Louisiana knows, Garrett said, “a true change to a state boundary is done by Congress, or a judge ruling on some case.”

An august panel of nine judges, the US Supreme Court, did rule on that question in 1960.

A painfully precise decision clearly addresses attempts by Louisiana, Mississippi Texas and Alabama to claim limits of nine miles extending into the Gulf.

Three-mile limits for Louisiana, Mississippi and Alabama are the law of the land.

Texas is permitted its continued claim of a nine mile limit because that was its limit before statehood, when it was an independent republic.

The High Court also let stand – in a separate decision – Florida’s claim of nine miles, based on the U.S. government’s acceptance of that clause in the state’s constitution, when it was re-admitted to the union after the Civil War.

The federal shrimp permit – itself a source of contention between fishermen and regulators – has been required since 2006. Only vessels that had been shrimping continuously after 2003 were allowed to apply for them.

Those permits are no longer issued, and so vessels that entered the fishery after 2003 can only get them by buying them from another fisherman who no longer uses it. The permits, which cost $25 when issued, can therefore now cost $1500 or more if sold from one fisherman to another.

“The permits are in a moratorium,” Garrett explained. “No more are being issued. Any shrimper who wants a permit must find one that is available for transfer.”

LDWF officers, who patrol within the three mile limit, do not enforce the federal permit requirement.

NOAA’s own enforcement officers do. So does the Coast Guard.

“If the vessel has a permit but it’s not onboard the fisherman may receive a citation,” said Coast Guard spokesman Jonathan Lally.

If a required federal permit is expired for only a few months, Lally said, a citation may be issued. If other violations are found on board a vessel with an expired permit the fisherman’s catch may be seized.

If the vessel has no federal permit at all or it is expired for a longer period of time than two or three months, the Coast Guard may also seize the catch.

Seizures, Lally noted, are only done if authorized by NOAA officials.

Discussions are on-going regarding the future of the federal permit overall, with shrimpers and some fisheries managers maintaining that the resource – the shrimp themselves – are an abundant annually-renewing crop. Environmentalists favor continuation of the limited-entry permit system because of concerns about shrimping’s effects on other species that are incidentally caught by trawls, such as game-fish.

The most recent interest by Louisiana in maintaining a nine mile limit rather than its legally allotted three miles arises from its desire – as well as the desires of Mississippi and Alabama – to do state management of the recreational red snapper fishery.

What sport fishermen see as onerous regulations on snapper have been imposed by the feds, and a nine-mile limit is one way state officials see as supporting the recreational industry. Attempts to increase the boundaries continue in Congress and there is also a move by the states to have specific compacts made regarding snapper.

Commercial shrimp fishermen have balked at being made cannon fodder in that particular war by the potential for misunderstandings because of Louisiana’s dogged stand.

Montegut shrimper Lance Nacio, who sells catches under his own Anna Marie brand name and often operates legally beyond the three mile state limit, has heard of some of the questions raised by other shrimpers, but has himself abided by the federal rules and advises others to do the same.

“I have the permit for both of my boats because we need to follow all the rules and regulations that are out there,” said Nacio. “We have to fish according to law.”

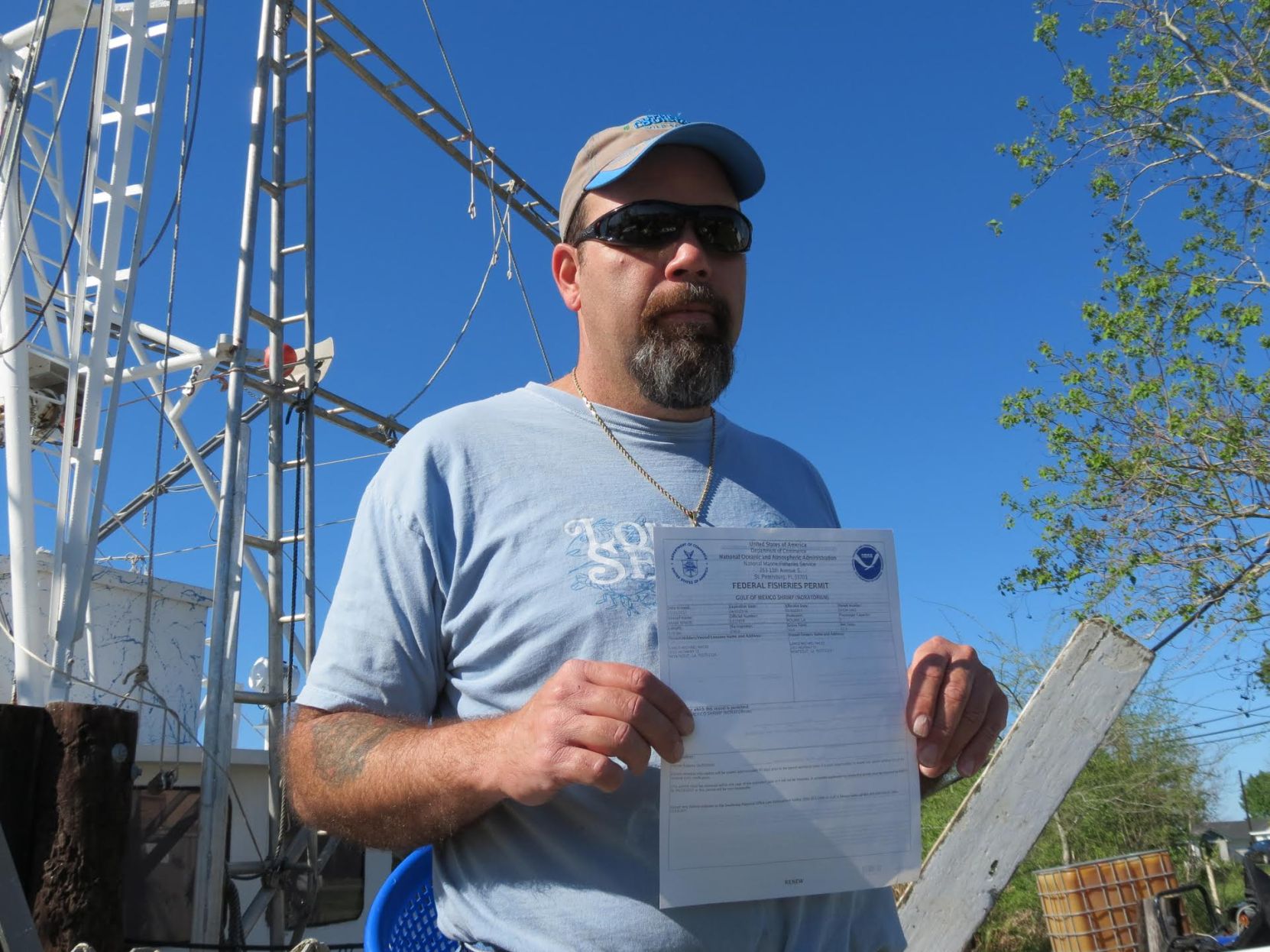

Montegut shrimper Lance Nacio shows his recently renewed federal Gulf of Mexico shrimp permit.