Local lawyers donate extra line of protection for deputies

July 19, 2016

Piper lands local high school job

July 22, 2016The death last week of a Houma teen, allegedly at the hands of his 16-year-old cousin and their 14-year-old friend, drives home a painful awareness for local community leaders. They acknowledge that a subculture which glorifies urban street violence continues to have a local stronghold, threatening to swallow a generation of young black men and others to come.

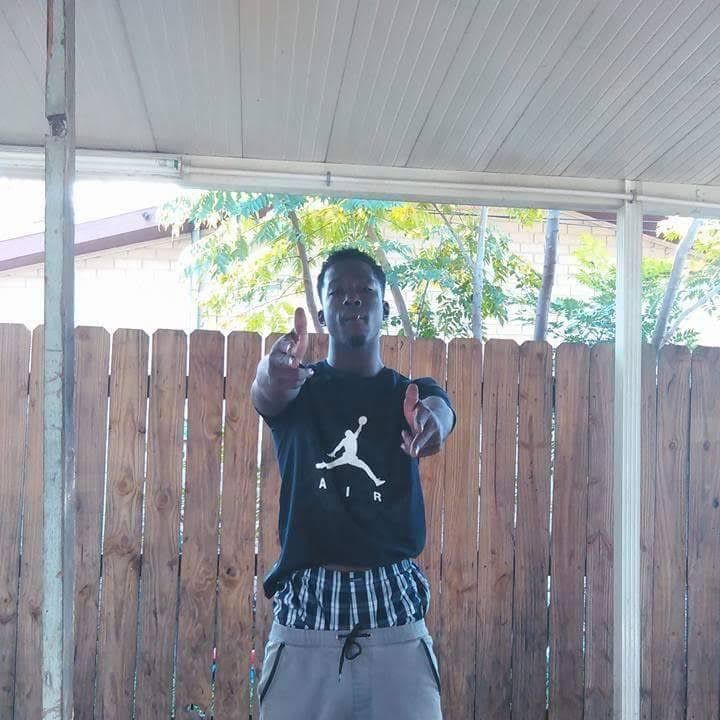

The body of Roderick “R.J.” Davis, pierced by multiple gunshot wounds, was found at around 5 a.m. July 11, on the well-tended grass of Scott Lane Park, a multi-purpose field in central Houma used for sports leagues and children’s Easter egg hunts. The shooting, city police determined, occurred around 11:15 p.m. the night before, when they responded to reports of shots fired in the vicinity.

No guns were found, but a small quantity of illegal drugs was recovered.

Within 24 hours, police had three teens in custody. One, a 16-year-old who lives on Westside Boulevard, was released within a day due to lack of evidence, law enforcement sources said. The victim’s next-door neighbor and cousin, Denzel Brown, 16, remains in custody and will likely be prosecuted as an adult. He is currently held in a special juvenile cell at the Terrebonne Parish jail. Zamante “Shank” Alvis, 14, of St. Louis Street, is being held at the Terrebonne Parish Juvenile Detention Center. Authorities want him prosecuted as an adult as well. A grand jury will determine whether one or both will be charged with 2nd degree murder. The investigation is not complete, and while there is currently no evidence to warrant holding of the unidentified 16-year-old, charges are still a possibility.

At a memorial for the slain teen at the park last week, friends and relatives gathered, offering prayers amid wails and tears. Some left candles at the site, and they spoke of how RJ would be missed.

“YOU CAN FIND YOURSELF DEAD”

Tears were shed as well for the community itself, and the impact of a life lost and others ruined, as some who were present used the gathering to share a message that violence must end.

“The black-on-black crime has to stop,” said 19-year-old Rashawn Brown, brother of Denzel Brown and also a cousin to RJ Davis. “Stop carrying guns and stop playing with them or you will end up in a place where you don’t want to be … You can find yourself dead or in trouble or in jail.”

Another cousin, 19-year-old Jamonta Brown, voiced a similar lament.

“All of us black people should get along and stop running in the streets,” said Jamonta. “We need to stop killing each other. We need to do like we used to do when we were small, come to the park, play ball, get along.”

Their message is one community leaders have long wished to see adopted by local youth, but they acknowledge an uphill battle. Gun violence in the Bayou Region is nothing new, and it is not limited to black victims or perpetrators. But this particular brand of intra-racial mayhem is at the moment most sorely felt in neighborhoods like this one, a lower middle class enclave of wood-framed houses and bike-riding children.

Jerome Boykin, president of the Terrebonne Parish NAACP, grew up in the neighborhood and says denial of the problem costs lives and must cease.

“It is part of the culture, part of the young generation that is making it happen,” Boykin said. “There is no excuse for it. There is no excuse for black on black crime. We cannot blame the white man. We do have to involve our leaders and ministers and others in the community, to try and talk to our youth if they are not on the right path and encourage kids to stay in school. We have put the KKK out of business. We are responsible for more black deaths here than they were.”

HAUNTING VIDEO

It is believed that the death of Roderick “RJ” Davis may have been the result of a dispute, related to allegations that he stole a firearm from one of the other teens, but the facts are still under investigation.

Interviews with friends and relatives of Davis and those accused paint a chilling picture of teens for whom possession of a pistol is a rite of passage conferring manhood, and who have little attachment to positive and traditional goals and ambitions.

A music video called “Dream,” shot in the same neighborhood by a young producer from Thibodaux, made social media rounds in the days after RJ’s killing.

(To see a portion of the video, click here. WARNING; video content may be offensive)

In a chilling blend of cinema verite and apparent prophecy, a teen identified by friends as “Shank” Alvis appears to be among those waving around a semi-automatic handgun and an assault rifle. It is not known whether the guns are real or replicas. The Times made its inquiries about its origin. Gunplay, dancing and faux violence – including a simulated drive-by shooting – are accompanied by a hypnotic beat to which a young man chants and raps about the Oct. 8 shooting death of 18-year-old Corey “Bugg Petty” Butler.

“He got shot up in the Yee, he’ll never see his baby,” the lyrics state, Yee being a reference to Morgan Street, and also incorporated into the group name chosen by a loose-knit crew of local young criminals, who refer to themselves as “Yeeway.” They also use “Yeeway” as a social media hashtag. “I did it on my own, nobody showed me the ropes … I remember no food in the kitchen.”

While the video expresses sadness for the death of “Bugg,” it offers no redemption, just tacit, almost playful acceptance of the way things are.

Houma detectives have seen the video and are aware of it and other expressions of the societal street norm in central Houma.

The youngsters accused of involvement in the killing of RJ are seen by the police and others in the neighborhood as low-rent versions of “Yeeway,” referring to themselves as “Oneway,” also used as a social media hashtag.

CONFLICTING STORIES

Video from neighborhood surveillance cameras has been helpful, law enforcement sources acknowledge, as have witness statements. The Times has conducted interviews in the neighborhood to determine some of what the police have learned, but conflicting stories and statements emerge.

For the immediate family of RJ Davis, the pain of loss is great, but they have declined to discuss his life or his death.

The RJ they remember appears on a local newspaper page from 2009, handing out hurricane supplies as part of an NAACP relief effort, with his cousin Jamonta.

That Davis had a history of conduct problems is well known in circles of educators and justice professionals, who spoke of time spent in state juvenile custody. Such background, however, is not known to include crimes involving drugs or violence against others. His cousin, Jamonta, has described him as a “protector,” and questions claims that RJ was a creature of Houma’s street culture. Another family member recalls him as always respectful toward elders.

But there is also evidence of conflict. Neighbors say that the night before he was killed, RJ was engaged in a dispute with Shank and another youth, who allegedly claimed he had stolen a gun from one of them.

RJ’s aunt, Schenika Brown, is among alleged witnesses to the Saturday exchange.

One youth was across Stovall Street from her home, Schenika said, in the parking lot of a convenience store, “hollering across the street at RJ.”

Shank was on the side of Stovall Street where the Brown residence is located, near the corner of West Park Avenue. Both the youth across the street, who is not being identified by The Times because he has not been charged with a crime, and Shank, witnesses said, were armed, as was RJ.

Schenika said her son, Denzel, who joined her out on the street due to the commotion, did not take part in the dispute.

Both Schenika and another witness say Davis displayed a black semi-automatic handgun during the encounter but did not point it at anyone.

Both of the witnesses said Davis announced “I am gonna catch me a body and kill him.”

“THEY TOTE GUNS”

The next night, Schenika said, her son Denzel was home, a claim disputed by other witnesses, who place him at the park with Shank, RJ and the unidentified teen. Authorities say other evidence places him at the park as well. But all accounts are under review.

A nearby resident told police of hearing gunfire at around 11:15 p.m., recalling three loud discharges that went “boom-boom-boom” and two others, described as “pop-pop,” which could indicate more than one weapon was fired. Police could not confirm whether that is the case.

Two young men, believed to be Denzel and the unidentified youth, are seen exiting the park on video, walking swiftly. One, according to a witness, said to the other, “Oh my God I think we killed him.”

Police responded but found no initial evidence of anyone having been injured. It was not until the next morning at around 5 a.m. that a body was discovered by a passerby. That morning Denzel was questioned in his home, and officers then left.

Schenika told them – as did her son – that he was sleeping when the killing occurred. Officers later returned and arrested him. The unidentified teen, with counsel, turned himself in and was later released. Shank turned himself in and was arrested.

“They are all going by hearsay,” Schenika said. “Denzel was not involved. He was always afraid of these boys, I would see it in his face and expression. They tote guns and stuff like that. He was terrified.”

Fear of what occurs on the streets, say young people in central Houma who reject the subculture of violence, is rampant.

“I used to see them playing with guns,” a neighborhood teen said of Shank and RJ. “I would have called the police but I am terrified, I am scared they will kill me.”

Attempts to locate family members of Alvis or the unidentified youth were not successful.

ANSWERS SOUGHT

As the police continue their investigation, public officials lament the violence.

“We as a community need to start coming back together,” said Parish Councilwoman Arlanda Williams, within whose district the killing occurred. “The church was the head of our community. I am an elected official but there are servant leaders here, appointed by Christ, and we need to stand as one to make sure that it is understood that all lives matter.”

Unaddressed social problems, Williams said, including poverty, lack of mental health services and availability of positive recreational and social experiences all play a role in youngsters turning too easily to violence. Steps are already being taken within the community she said, including meetings of ministers.

“Often times people look at juveniles as troubled children and just that, and count them out like they have no hope instead of instilling hope in them, giving them an opportunity to make it,” Williams said. “We need to find out why a child is angry. We don’t need to count them out, we need to count them in.”

CHANGING VALUES

Councilman John Navy, whose east Houma district has transformed into a killing ground over the past year, says families, communities, government and other entities are finding as “too acceptable” instances of intra-racial violence.

“This trend is continuing and no one seems to be addressing it and having that conversation,” said Navy. “Everybody, black, white, Hispanic, all need to come together and have that conversation.”

“The value system has changed, culture has changed, religion doesn’t play a valued role anymore, these things are not instilled in these kids, these Christian values,” said Navy.

As officials discuss policy and resources, mentors who work with youngsters, like Justin “DJ Juice” Patterson, an educator familiar with the problems they face at street level, say there are things parents can do right now to keep them safe.

“Monitor their social media, their friends, know what they are looking at on the screen,” Patterson said. “It’s 10 o’clock, do you know where your children are? There is no reason for teenagers to be out on the streets late at night after dark because there is nothing there for them that is good for them.”

No. 9 Central Houma street violence draws words, concerns

The murder of a Houma teen, found dead in a park near the Bayou Towers senior housing complex, drew expressions of concern from local political leaders and renewed calls for aggressive mentoring of youth at risk from street violence.

The body of Roderick “R.J.” Davis, pierced by multiple gunshot wounds, was found at around 5 a.m. July 11, on the well-tended grass of Scott Lane Park, a multi-purpose field in Central Houma used for sports leagues and children’s Easter egg hunts. The shooting, city police determined, occurred around 11:15 p.m. the night before, when they responded to reports of shots fired in the vicinity.

No guns were found, but a small quantity of illegal drugs was recovered at the scene.

Within 24 hours, police had three teens in custody but released one for lack of evidence. Criminal proceedings are still pending against a 16-year-old cousin of the victim and a 14-year-old.

Times coverage of the case spotlighted a distressing subculture of violence in some neighborhoods reflected by hip-hop videos that include rampant displays of semi-automatic weapons. Police have tied the Davis death and other murders stretching back to 2015 to an out-of-control culture of young drug entrepreneurs.

Terrebonne Parish Councilman John Navy introduced several ordinances to help police keep a closer watch on neighborhoods and continued encouragement has been given to neighborhood watch groups, as police work on better relations with community members to aid them in investigations.