Why? Missed connections cited as possible reason for tragedy

February 5, 2013

Lawmakers name priorities as session nears

February 5, 2013After being tipped off by a man who was walking past on that Sunday in August, police arrived at the blue house on West Seventh Street to find a child’s severed head near the street. Moments later Jeremiah Lee Wright exited the home and gazed from the porch.

Seventeen months ago Wright held 7-year-old Jori Lirette over the kitchen sink and dragged a saw across his son’s neck. “The more I cut with a hacksaw, the more I saw it was real,” the now 31-year-old father of none would tell a doctor almost one year later. Wright went on to chop off Jori’s arms and legs, and then he stuffed them with his torso in a garbage bag.

Wright had a moment of insight the night before, he’d tell other psychiatrists and psychologists, when he realized Jori – who used a wheelchair, was fed through a tube and was diagnosed with cerebral palsy – was presented to him not as a biological son conceived with his live-in girlfriend Jesslyn Lirette, but as an inanimate plant in a government-sponsored social experiment. So father dismantled son while mother ran an errand.

District Judge John LeBlanc said Monday he’d have his decision as to whether Wright is competent to stand trial by Thursday afternoon.

If ruled competent, the stalled criminal proceedings against Wright would resume. If he is ruled incompetent, the suspect would likely return to the East Louisiana Mental Health System’s forensic division in Jackson, La., where doctors would once again be tasked with rehabilitating his mental state. Wright spent nine months at the facility after LeBlanc ruled him incompetent in October 2011.

Last week Wright sporadically cast his gaze toward a carousel of mental health specialists while they testified regarding his current mental capacity. The confessed killer sat hunched in the corner, never showing emotion, never speaking during the hearing, never altering the sunken disposition every doctor mentioned. A bulletproof vest covered his red jumpsuit, and for two days a denim jacket was draped over his shoulders, over his chained hands and feet. He occasionally closed his eyes and curved further.

Prisoner of a false reality

For the sake of LeBlanc’s decision, the inner workings of Wright’s mind at the time of Jori’s death do not matter.

But the delusional machinations that reportedly began creeping into the confessed killer’s head days, weeks, months before he took the saw in his hand were an omnipresent matter in the attempt to restore his competency.

Wright, defense experts testified, expects salvation in the coroner bursting into the courtroom holding up a plastic head, expects salvation when the coroner reveals Jori died of heart attack, expects salvation when this social experiment concludes with a declaration Wright was intelligent enough to decipher Jori was not real and that he took appropriate action. “He just believes he’s going to go to court and then go home,” testified Sarah Deland, a board-certified forensic psychiatrist who met with Wright on three occasions.

While acknowledging delusions are not mutually exclusive with competency, defense experts said the false beliefs Wright has expressed prevent him from thinking rationally about the case. Wright’s strategic compass and his abilities to testify at his own trial, determine whether opposing witnesses are distorting facts and decide who to call on his behalf are compromised, they said.

On at least one occasion, Wright deviated from his delusion, according to one of the doctors who authored an ELMHS report declaring him mentally fit to stand trial.

Glenn Ahava, a forensic psychologist at ELMHS, testified that Wright referred to Jori as his “son” and said he allowed Jori to watch him play video games and to watch television with nudity. This conversation is said to have happened 11 days before the report was released.

The report’s second author, the principal psychiatrist evaluating Wright at the facility, said he never believed Wright was in a state of delusion. The psychiatrist Mark Wilson instead said Wright lacked “delusional organization” and exhibited “inconsistencies in his presentation.”

Among the evidence contrary to delusions in Wilson’s report were notes written by hospital security guards – also trained in mental health. The guards’ correspondence indicated Wright may be exaggerating his symptoms in the presence of doctors while behaving a different way when outside of their purview.

The act of interpreting those messages, and other comments Wright made, was made difficult by the known pitfall of psychology: It can be double edged.

“A lot of times you can take it both ways,” Wilson said from the stand, demonstrating the difficulty of interpreting the meaning of a patient’s words. “I had a suspicion he knows what’s going on” but Wilson struggled to determine whether the statement was ironical or delusional. “That’s been the question throughout the stay.”

Defense counselor Cecilia Bonin, representing the Capital Defense Project of Southeast Louisiana, took the dichotomy of interpreting a patient’s words a step further when she pointed to the word “child” written in a security guard’s note to doctors.

Hospital security guards are always within arms-length of patients, and doctors to at least a minimal degree used their observations in judging Wright’s competency. The guards reported that Wright behaved “irrationally” around nurses and doctors but rationally when left alone with the monitors, and they scribbled messages on their logs that indicated Wright was able to understand he murdered his son.

On Nov. 17, 2011, a guard wrote that Wright said he wanted to get rid of the child and hopefully collect a Social Security check. The guard did not place the word “child” inside quotation marks, leaving Bonin to question whether Wright actually said “it,” as he had referred to Jori almost unilaterally.

Although it may seem trivial, the distinction between who used what word – which couldn’t be definitively stated – is important to gauge the veracity and intensity of Wright’s delusions. If Wright would have indeed said “it,” the comment would have been further proof of delusion, she argued.

Exchanges such as this one were common during Bonin’s cross-examination of Wilson, who made his notes and other hospital records related to Wright available to the defense, as mandated. Bonin would raise a concern, Wilson would check his notes, and definitive answers in the evolution of Wright’s treatment were hazy.

Rationalizing their judgment

The chief purpose of the ELMHS competency restoration program is to ready patients for trial, doctors testified. This process typically takes 90 days and has a 70 percent success rate, the hospital’s chief of staff testified.

Psychological issues become secondary, though the doctors stressed they do not gloss over the process of diagnosing mental health problems. It’s just that a psychological issue that interferes with a patient’s meeting specific courtroom- and case-related criteria would be given more priority than a delusion, which, again, doesn’t necessarily impair competence.

The standard measuring sticks of competency are referred to as the Bennett criteria, which were derived from a 1977 state Supreme Court ruling. The checklist administered by ELMHS doctors prompted Wright to respond on things such as the distinction between first- and second-degree murder, various pleas and their meanings, rules of the courtroom, ability to protect himself and his rights, his available defenses and potential verdicts and their penalties.

The criteria can be met via a variety of responses. For example, state expert Manfred Greiffenstein testified that Wright had an understanding of the severity of his offense and potential punishment he faces when he said he would prefer to be executed via the guillotine.

That Wright “contemplated a painless death tells me he takes the charge seriously,” said Greiffenstein, who examined Wright for roughly four hours at the Lafourche Parish Detention Center last November. Wright understands the guillotine is not a realistic option – lethal injection would be the course of execution – but he expressed that it would be his “preferred method,” Greiffenstein said.

It could also be interpreted as a way that Wright’s delusion does not impair his competency.

On the other hand, the defense took exception to some of the recorded answers. Defense counselor Mildred Methvin quizzed Wilson about Wright saying he could consult with “the bailiff” on his legal quandary and saying he could call “just about anyone” as a witness.

Wilson, who examined the patient for more time than any other expert, said Wright sometimes “chooses to be flippant.” He said he based his decision on competency largely over the observations he made over the course of nine months. Not all of his observations were chronicled in the report.

The fact that the opinions of two examining psychologists at ELMHS – one left mid-treatment – differed dramatically enough that they testified in favor of opposite outcomes is a weighty and symbolic example of the duplicitous testimony LeBlanc had to unravel.

Robert Storer, the psychologist who left ELMHS in January 2012, twice took the stand to testify on behalf of the defense. From the third day on, Storer listened to the testimony. Under questioning, he said his services were retained as a consultant, and that his standard rate is $200 per hour.

“I don’t think they are incompetent,” Storer said, under questioning by District Attorney Cam Morvant II, of his former co-workers. “I think they have missed it on this one.”

As discussed in his initial testimony, Storer administered several tests on Dec. 19 and 20, 2011. One of the tests heavily scrutinized was the Personality Assessment Inventory he administered. Storer declared this PAI invalid because he said Wright had responded too positively, hiding symptoms and “faking good.”

Despite the test being declared invalid, Wilson used the results in his bi-weekly progress notes regarding Wright’s rehabilitation. While this in itself is questionable, according to the defense, counselors also alleged that he incorrectly stilted the invalidated results in his notes.

Wilson first mentioned the results without qualifying them invalid in his Jan. 6, 2012 progress note, writing they showed “no obvious evidence of psychosis.” He does not note that it produced no evidence that Wright was not psychotic, and he uses the results in the same manner in each progress note from Feb. 2, 2012 through April 16, 2012.

Storer said using the PAI results in that manner “absolutely is not” a correct reading.

Wilson said he operated from the beginning under the assumption that Wright suffered from psychosis not otherwise specified – a diagnosis first delivered after the suspect was discharged from a weeklong stay at a mental health facility five months before the crime.

Glenn Ahava, a forensic psychologist, joined ELMHS in March, 2012. Near the end of May, he rescored the invalid PAI by hand (it is typically scored via a computer to root out errors, Storer said) and validated its results.

While the PAI made it into the hospital’s final report, an Evaluation of Competency to Stand Trial – Revised examination did not. Wright failed the ECSTR, primarily because he refused to complete it, according to Wilson.

Defense counselor Mildred Methvin said in her closing argument that was indicative of a pattern shown in the ELMHS report. No tests that differed from the authors’ opinions made the final draft, nor did the findings of a sanity commission in 2011 that led LeBlanc to declare Wright initially incompetent.

“That’s a criticism of report style writing,” Morvant said in his closing rebuttal, adding that neither Ahava nor Wilson had anything to gain professionally for clearing Wright for trial. Wilson “never, never, never went away from the fact this was a deliberative process he took very seriously” and testified that he considered the results of all tests – even the ones he didn’t include in the report.

The report was perhaps the keystone piece of evidence declaring Wright for trial, as the doctors who released it were ostensibly under no pressure to send the suspect back into the justice system.

Because it is so vital to the case, the defense took aim at the report and its authors. In her closing argument, Methvin accused Ahava and Wilson of “filtering evidence,” producing a “totally flawed” document “cherry picking” tests that championed their hypothesis and using an “I-said-no” rationale in doing so.

The counselor acknowledged the tragedy Wright’s action inflicted on the family and friends of Jori Lirette, but finished by saying: “To require him to face trial with his psychotic problems would be a violation of due process.”

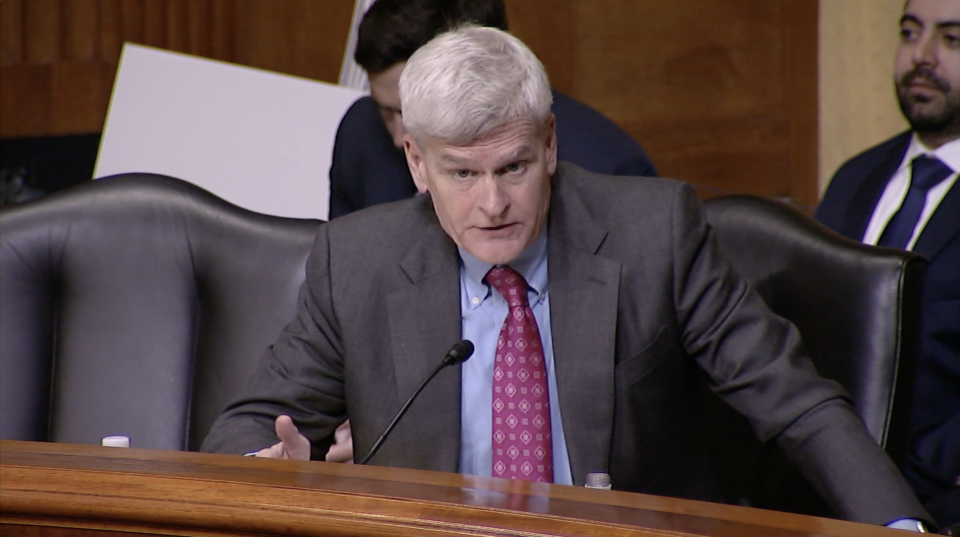

Jeremiah Wright is escorted to his competency hearing by Lafourche Parish Sheriff’s Deputies. Wright is accused of the first-degree murder of Jori Lirette, his 7-year-old disabled son.