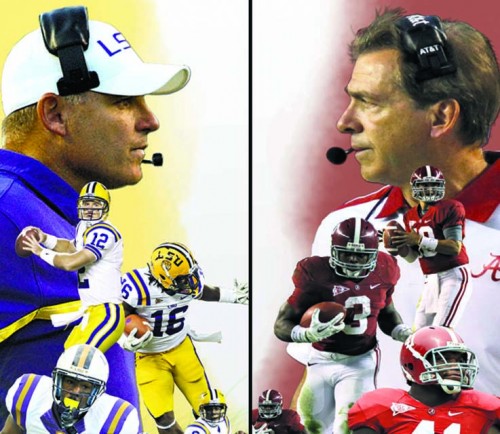

Round II: Goliath v. Goliath

January 5, 2012The Ameen Art Gallery (Thibodaux)

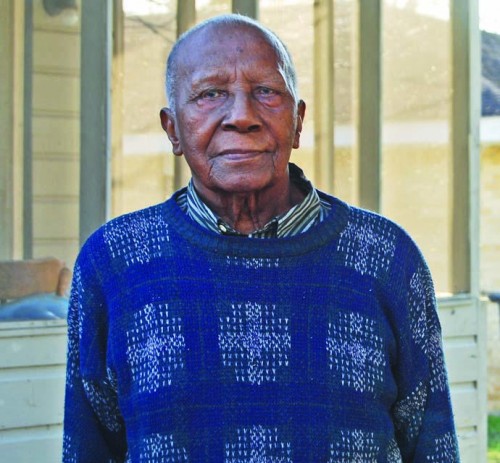

January 9, 2012As a member of the all-black Buffalo Soldiers Division that saw one year, two months and 10 days of constant combat during World War II, Emanuel Skinner Jr. saw firsthand the horrors of trench warfare.

At 93 years old, the Morgan City resident can still mimic the cacophony of mortar rounds, 500-round-per-minute artillery guns and screaming bombs that became as much of a fixture in his young adult life as cold beer is for most Americans.

“People don’t know about the wars,” Skinner said after telling of soldiers who crossed a mountain ridge and never returned. “It’s tough. I think about I could have been some of the fellas that didn’t come back myself.”

Skinner can’t recall the towns in which he fought, but he remembers landing in Naples, Italy in 1944, a rifleman carrying a M1 Garand to the front lines in Europe as a member of the 92nd Infantry Division, the last all-black U.S. military unit.

He remembers the mud he would lay motionless atop or crawl across, that sometimes he stood in foxholes carved out of Italy’s rolling hills and mountains for two days at a time and wading 50 feet through a body of water called “Island River.”

“There was a boy next to me, then ‘Boom,’ and the water splashed up,” he recalled. “He had stepped on a foot mine and it took his whole foot off.”

The serial number etched into Skinner’s dog tag? “Thirty-eight, eighteen, sixty-nine, sixty-three,” he rattled off with the quickest pace he used during an hour-long interview. “I never forgot that.”

He remembers the time a commanding officer shouted “Every man for himself,” and can describe an instance when a fellow soldier he walked alongside was shot in the hand by a sniper, then crawled through the mud, leaving a trail of blood behind them.

He can still recall a moment when his foxhole was fired upon. Skinner was unscathed, but the man next to him was not. “He laid right beside me and died,” he said.

And then, there was the time when he watched a mortar round decapitate a young man and wartime friend from Jeanerette. “It hit my buddy on the head and took his head clean off. I saw that.”

Skinner didn’t discuss killing enemy troops, but his daughter answered the question with a somber voice. “He did. With a bayonet, he did. My mom said he had nightmares when he came back for a long time.”

“I hit what I aimed at,” Skinner said later.

A lifelong St. Mary Parish resident with seven siblings, Skinner was drafted into the U.S. Army in 1941, just before his 23rd birthday. He was the only person from his family to serve in the Military, and he’s the only one still alive.

A military police officer until that was disbanded, Skinner was shipped overseas with the buffalo soldiers, a moniker placed upon all-black military units by Native Americans after the Civil War.

“The war changed my life,” Skinner said. “I never was a bad fella. I thought about how I come back (after the war) and what I went through. That changed my life. I had a lot of friends, but I left them alone. I’m going to tell you something. Something told me to leave those people alone and get on the Lord’s side. That’s where I’ve been now.”

After his discharge, Skinner spent most of his life as a general laborer at various shipyards in Morgan City and New Orleans, including St. Mary Galvanizing, Avondale and McDermott.

Juxtaposed with the horrors of war on the front line, for this Baptist man who said he drew his drive to survive from family letters mailed out of Morgan City, was military leave to the city of Rome. While there, Skinner toured the Vatican, an unattainable dream for so many people. “It was beautiful.”

But it was back to the war. In one of the most chaotic moments of his tour, when the formation of battle was broken and survival trumped all else, Skinner’s company lost its commander.

“He was on our front line,” Skinner said. “This was when he hollered, ‘Every man for himself.’ I waited for him, but some of them didn’t. I couldn’t get back to help him, because I wouldn’t be here now if I would have. I was in the foxhole.”

Skinner locked his fingers together to emphasize a relationship between himself and a close wartime friend, the both of whom were gallivanting with ladies in a residential district.

They walked into a building and were tipped off that they were in enemy territory with warnings of “Paisan,” a term Italians used to recognize one another as countrymen and one that Skinner’s regiment used in the same vein as “Kraut” and “Gook” and “Jap” were spoken by veterans who have fought other battles.

Skinner suggested they head to the basement and 20 minutes later, the rumbling explosions of bombs cascaded above their shelter, destruction overhead.

“We went down in the basement, they brought down the buildings and killed a bunch, but they didn’t kill us because we were in the basement,” he said. “We came out the other way and a company commander said it had been hit. So we got back with our company.”