Sugar yielding high content, low crop weight

October 21, 2015

Chatman honored by peers

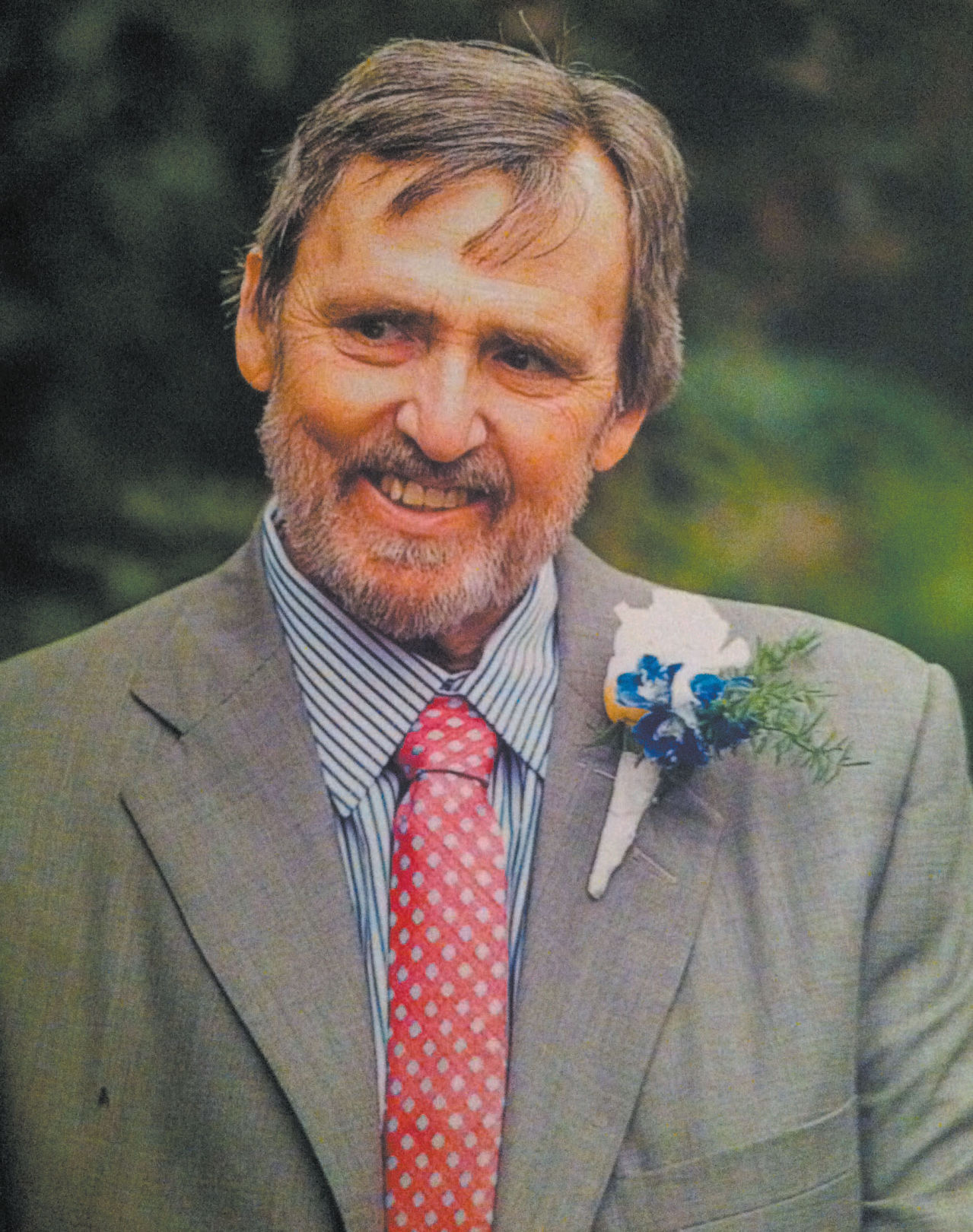

October 21, 2015A lawyer who devoted his life to representing in court wayward youth charged with crimes, a man who viewed his work as a calling to protect the most vulnerable children, and loving husband and father. Levy died of colorectal cancer at 64, on Sunday, Oct. 4, 2015.

Bernard Freeland Levy was a lawyer who devoted his life to giving a voice to the most vulnerable children in trouble with the law.

Bernard was born in New Orleans on Jan. 4, 1951, to Nathan and Elizabeth Levy His father was an attorney and his mother a homemaker.

The family had a total of seven children. By the time Bernard was 1-year-old, he had taken to watching over his infant sister, Martha, a role he never abdicated throughout his life. He would sneak her crackers between the slats of her crib.

When he was 5, Bernard contracted Tetanus, a serious bacterial disease that affects the nervous system, leading to painful muscle contractions, particularly in the jaw and neck muscles. Although advancements in the treatment of the disease were made at the time, the mortality rate was still 65 percent. After many months of shots, pain and fighting for his life, Bernard survived.

His mother was so amazed by his survival that she asked the Catholic Church to investigate if her son’s case could be considered a miracle. The church eventually determined it wasn’t, though the many children who were represented by Bernard later would likely disagree.

A few years after Bernard’s recovery, the family moved to Morgan City where Nathan began practicing law. There, Bernard and Martha attended Central Catholic High School. He played football and became fairly popular with his classmates.

Bernard was an unruly youth at times. One weekend during his high school years, Nathan and Elizabeth went out of town for the weekend, leaving Bernard and his siblings at home. Nathan was a very strict father and left explicit rules, as well as the consequences for breaking them in a note on the refrigerator.

“But before they left town, we had invited pretty much the whole high school over to the house,” Martha recalled. “We did pay for that.”

Bernard graduated from college and attended Loyola University of New Orleans College of Law. Afterward, he moved to Monroe where he practiced at a law firm, representing a bank where Barbara Marx worked. A fellow attorney introduced the two at Bernard’s 27th birthday party.

“That was it for me,” Barbara said. “I thought he was adorable. It was kind of wild days back then in the late Seventies.”

A year later, they were married. Together they raised three children: Bernard, Marion and Anna. Tragically, their first son, Nathan Isaac, died during birth.

The couple moved to Houma where Bernard began practicing for what is now known as the law offices of St. Martin & Bourque. He practiced with the firm for a year before he left to start his own practice.

It was then, during the early Eighties, that he began working as a public defender with the 32nd Judicial District Indigent Defender Board, now known as the Office of the District Public Defender, representing those accused of crimes that couldn’t afford a lawyer.

Among his clients were juveniles.

Bernard soon found he had a passion for representing wayward children who came, many times, from broken homes. The things the children endured was something that weighed heavily on his shoulders, though he never talked to Barbara about it.

Barbara said her husband developed a passion for his work over the years.

“It’s about as in the trenches as you can get,” she said. “He believed that if he didn’t speak up for these kids, nobody would.”

Bernard served impoverished children caught in the Terrebonne legal system’s web. He literally lost sleep over it at night.

“He would bring it home with him,” said his daughter, Anna Levy Plaisance.

With his own children, Bernard was kind and gentle, no doubt because his own father wasn’t. His experiences growing up, both with his father and his own tendency to break the rules, were likely his motivation to help local children, his wife said.

Despite the long work hours, Bernard always made time for his children. He often took them to see the New Orleans Zephyrs or Saints games, fishing or just enjoying time out on the water.

He never tried to impress his views on his children, nor did he try to tell them what to do with their lives. His son, Bernard “Ben” Freeland Levy Jr, did say that his father told him never to become a lawyer. Ben said his father did not enjoy the actual practice of law, but rather viewed his work as giving voice to troubled children.

In fact, he continued to work for a year after being diagnosed with colorectal cancer because he couldn’t bear to leave his young clients without representation.

A few days before Christmas each year, Bernard would buy a dozen or so large pizzas and bring them to the children housed in the Terrebonne Parish Juvenile Justice Facility, colloquially known as the Ashland Jail.

To them, it meant the world. When Bernard’s son, Ben, was a little older, Bernard asked him to come with him to deliver the meal.

“And I told him that I didn’t want to do it because it made me sad to go see these less fortunate children. He told me, ‘You know, it makes me sad, too, but I don’t do it for me to feel good,”‘ Ben Jr. recalled. “‘It’s not for me,’ he told me. ‘For someone to get the one day that they get to look forward to, if that means that I have to try [living] in their circumstances for a few hours, then it’s worth it.'”

Bernard Freeland Levy was a public defender who represented hundreds of wayward youth charged with crimes in Terrebonne Parish over the course of his 35-year career with the Office of the District Public Defender. He viewed his work as a calling, according to those closest to him.