Tarpons powered by 1-2 punch offensively in 2016

September 4, 2016DIGITAL DIALOGUE

September 6, 2016A university’s attempts to reconcile a troubling chapter in its history is echoing in Terrebonne and Lafourche, as researchers connect dots spanning centuries between slaves the school once owned and sold, and their living descendants.

Georgetown University President John DeGioia last week announced plans for contrition that are to include preferred admission for descendants of the school’s former slaves, a public memorial and creation of an institute to study slavery itself.

More than 50 of the 272 slaves that Georgetown’s Jesuit priests sold off in 1838 to pay mounting debt ended up in Terrebonne Parish, and later sold to other plantations including some in Lafourche. The remainder of the 272 went to plantations in Iberville and Ascension parishes. The transactions brought Georgetown $3 million.

Researchers are focusing on modern-day members of the Mahoney and Queen families, who primarily live in Raceland and Mathews.

“This original evil that shaped the early years of the Republic was present here,” DeGioia said at a commemorative gathering on Georgetown’s Washington, D.C. campus. “We have been able to hide from this truth, bury this truth, ignore and deny this truth.”

In 2015 the university convened its Working Group on Slavery,

Memory, and Reconciliation “to explore this history, to engage the community in dialogue, and to outline a set of recommendations to guide future efforts. The report of the Working Group, which DeGioia referenced last Thursday, “is one step in a longer-term effort that will be informed by dialogue and engagement with members of our community and descendants.”

Overall the project has thus far identified some 2,000 descendants, both living and dead, of slaves held by Georgetown.

FLATBOATS ON THE BAYOUS

Researchers have been poring through archives at the clerk of court offices in Terrebonne and Lafourche to further the effort. They have initiated contact with various potential descendants. Their purpose is to identify as completely as possible the human connections from the past to the present. Ancestry.com is donating DNA kits to aid in the process.

“I learned that the Terrebonne group were the first group to arrive anywhere in Louisiana from Maryland,” said Baton Rouge-based researcher Judy Riffel, who leads the Louisiana effort. “They were gathered up from two plantations and sent on ships, it was fifty some-odd in the Terrebonne group that they put on a boat and sent in June of 1938 and they arrived in New Orleans in July. A document in the courthouse lists everyone who was on the boat. Some missed the boat and one was sent a few months later.” Riffel said she believes that after arriving in New Orleans, the slaves were sent to Terrebonne on flatboats.

Their destination was a sugar plantation owned by Dr. Jesse Batey. Its lands made up much of what is now the community of Gray, just south of Schriever and north of Houma. Batey, whose name is sometimes spelled Beattie, was a doctor of dentistry whose holdings were expansive. The deal was rather complex, according to documents released by the university.

Founded in 1789 as Georgetown College, the school from its beginnings relied on income from tobacco plantations worked by enslaved people. Jesuit priests gained control of its board.

The plantations continued to operate. But in the 1830s two prominent Jesuit priests, William McSherry and Thomas Mulledy, determined that the scheme was financially inefficient.

Small sales of slaves took place. Then in 1838 Father Mulledy was given the task of selling off the remaining slaves.

He found willing buyers in Jesse Batey and his business associated, U.S. Rep. Henry Johnson, a former governor of Louisiana and uncle of a Georgetown student.

SLAVES WANTED ROSARIES

Jesuit officials in Rome frowned on the idea of a mass slave sale, instead favoring their liberation.

Mulledy demurred, and Rome put conditions on the sale. Families would not be separated. The slaves, who had been baptized and practiced Catholicism, would have their religious needs met and accommodated.

Historical records and accounts based on them strongly indicate that not everyone in the Jesuit community of Maryland was so sure.

The Rev. Thomas Lilly wrote in a letter to superiors that slaves from St. Thomas Manor were “dragged off by force to the ship and led off to Louisiana. The danger to their souls is certain.” Another Jesuit, Peter Havermans, wrote of the slaves’ “heroic courage and Christian resignation.”

Haverman related that

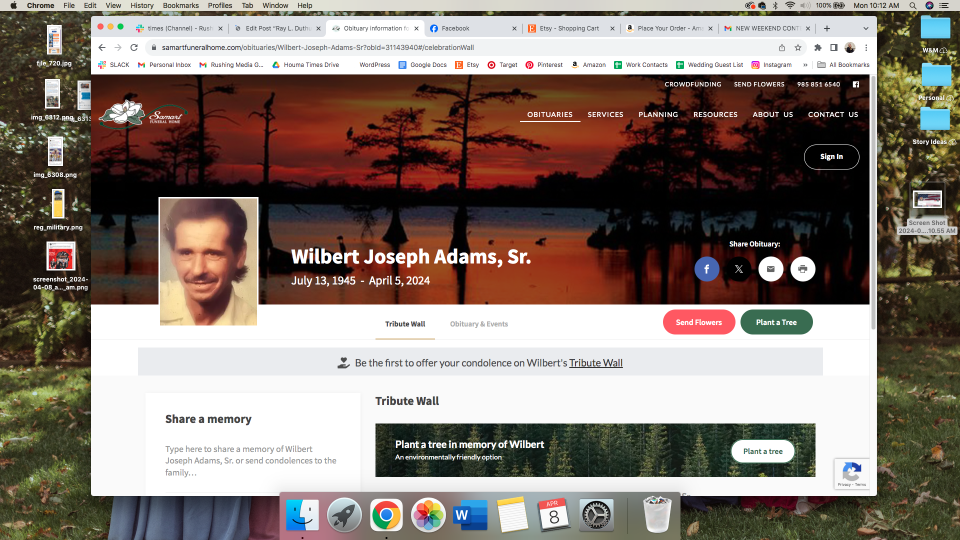

Melisande Short-Colomb, a descendant of slaves held and then sold en masse by Georgetown University priests in 1838, struggles with the legacy that’s been left behind by her history.

Officials at Georgetown University in Washington D.C. made their plans for reconciliation with descendants of slaves public last week.