In Laf. front porch could be a bus stop

May 13, 2015

Remembering Albert "Sugar" Guidry: Engineer instilled love of hard work, education in offspring

May 13, 2015Their friendship began in boyhood seven decades ago, and grew while in the service of their God.

As adults they continued that service – one as a priest and the other a dedicated lay servant of the Catholic Church.

And last week the Rev. Roch Naquin, now retired from full-time duties, and Bernard Dupre, a retired municipal employee, long-time altar server and usher, were re-united in service to a local church.

The Mother’s Day mass at Sacred Heart Church in Montegut, provided cause for the two men to reminisce about shared memories rooted in local culture, tradition and spiritual commitment.

In the wood-frame Montegut home that Bernard shares with his wife, Dorothy, the two men’s recollections reflect not just the personal history of each, but the community where their journeys began.

“It was a privilege,” Dorothy later said, referring to the experience of witnessing the two men sharing stories of the past. “It is so good knowing that for so long they still really like each other. It was very much a different time back then.”

Father Roch, as he is affectionately known by local faithful, was born in 1932 and raised in the remote Terrebonne Parish community of Isle de Jean Charles, where he now again resides, following a lifetime of assignments in south Louisiana parishes.

Bernard was born in 1937 near the banks of Bayou Petit Caillou, but raised in Montegut, commencing classes when he was 7 years old at Montegut Elementary School.

“I did not want to go to school,” Bernard exclaimed, recalling the school’s principals, “Mr. Austin and Mr. Pellegrin.”

The young Bernard much preferred trapping in the swamps and marshes with his father, something he had done from his earliest years.

‘Miss Chauvin and Miss Austin were the teachers,” he said. “Miss Chauvin flunked me in fifth grade and Miss Austin used to crack me hard on the knuckles with a three-cornered ruler for speaking French. Oh, the pain.”

Back in those days, both men recalled, local children were punished for speaking French, most often their first language.

“I’m still trying to learn English,” Father Roch quipped. “They would make us write 300 times ‘I will not speak French in school.'”

Because Isle de Jean Charles did not have its own parish church, a priest would drive from Sacred Heart in Montegut to Pointe-aux-Chenes, then paddle in a pirogue across the little bay to the island once a month, with altar boys in tow.

While on the island, the priest would celebrate mass, hear confessions and perform marriages, baptisms and occasional funerals.

All this was done in a single building that served as a church, school, dance hall and Antoine’s grocery store.

Father Roch was an island altar boy who participated in the ceremonies. So the two often served mass together, and found that there was enough commonality in their backgrounds – including the difficulties related to speaking French and coming from families who lived off the land – to make a foundation for friendship.

As the resident altar boy and the visiting server became fast friends, they would watch serial movies

like “The Lone Ranger” and “Cisco Kid” provided by the priest.

Once a year, on Holy Saturday, the islanders – Roch included – would make a pilgrimage to Montegut. “They would come by boat up Terrebonne Bayou and dock at Camille Pitre’s bar,” Bernard said, noting “always a few people never made it to church.”

Father Roch’s dad was captain of the school-boat that ran from the island to Point-Aux-Chenes.

“I was his engineer,” Father Roch said. “Meaning I started the engine for him.”

Father Roch first thought about the priesthood at age 13, but seminary admission required an eighth-grade education and the island’s school only went up to seventh grade.

He contends the seventh grade cut-off was “because they didn’t want Indian children to be educated.”

“Some of us would just repeat the seventh grade twice, then quit and go oystering,” he said, recalling that as his own personal experience.

Twenty-seven days on and three days off became his routine until his absence in church was noted by the local priest, the Rev. Gerard Peltier.

“He told my momma to send ‘her boy’ to him,” Father Roch said. “At that meeting, I admitted I still wanted to be a priest but couldn’t get the education I needed on Isle de Jean Charles.”

He recalls that the priest advised he go to a different school, and then worked on getting him into public and Catholic schools in Houma. Deep prejudices at the time resulted in rejections.

“But that did not discourage Father Peltier,” Father Roch said. “He approached the Sacred Heart Brothers who ran Thibodaux College.”

The college ran a fifth-to-12th grade program.

“They said if I could find someone to stay with, I could attend,” Father Roch said.

Peltier’s housekeeper, Mae Champagne, heard the story and talked to her sister Julia who lived in that area. Julia and Clinton Leger had three children, but two of them died in a pirogue accident on Bayou Lafourche. They took in the young Native American teen, and he spent the next two years at the high school.

In 1950, he enrolled at St Joseph’s Seminary in Covington and graduated six years later. Then it was six more years at St John’s Catholic Seminary in Little Rock for training in languages, theology and related subjects. Each day at 3 a.m., he recalled, his assigned task was to light the school’s boiler.

In 1962, Father Roch’s dream was fulfilled when he was ordained at St Louis Cathedral in New Orleans by John Patrick Cardinal Cody, then an archbishop. He performed his first Mass at Sacred Heart in Montegut, and for the next 35 years he served Catholic churches in Chalmette and around St Bernard Parish, Thibodaux, Theriot and Dulac.

He finally retired in 1997, and now spends his time working with Native Americans, visiting French people and the Cursillos in Christianity movement, which focuses on showing the Christian laity how to become effective leaders. He said he enjoys filling in for other priests as the need arises.

Bernard Dupre recalls that he and Father Rich shared a unique distinction during their younger years.

“We were always among the oldest kids in our classes because of the interruptions in our schooling,” he said.

Bernard graduated high school at the age of 21. Father Roch entered the seminary, leaving the equivalent of eighth grade at 18 years old.

The assigned job for Bernard in fourth grade at Montegut Elementary, starting the furnace in the mornings to heat the school, a task similar to Father Roch’s at the seminary.

“It was fired up with coal,” Bernard said. “But the coal was stored under a cistern and wet. That was a miserable job, trying to get wet coal to burn. All the classes were upstairs and the kids would skate in the open area downstairs.

“If you didn’t bring your lunch, you could walk to a store and pay 5 cents for a soda and 10 cents for a sandwich that was really just two pieces of bread and a slice of lunchmeat so thin you could see through it.”

He vividly remembers the first Mardi Gras Carnival in Montegut in 1946.

“The floats were built on sugar cane wagons and pulled by mules,” he said. “Druby Robichaux and Edwina Brunet were the first king and queen.”

Later, he attended Terrebonne High School. As Father Rich continued with his spiritual training, Bernard began a string of odd jobs, moving a secular direction, but never losing his commitment to the church.

“I would cut cane for 50 cents a day,” he remembered. “Once I worked as a chemist boy. I would pick up samples of molasses and cooked sugar to see how much sugar came out of a ton of cane. At a crab factory job, I would unload and steam the crabs and the women would peel them for the Indian Ridge Canning Company. Our families would buy crabs from the fisherman for 50 cents a bushel. If you just steamed them with no seasoning, that was the best flavor.”

In 1957, Bernard met his future wife, Dorothy “Dot” Bascle, at the dentist office where they both had appointments.

“It was Dr. Walton by the old Park Theater,” said Bernard. “He used green persimmon juice as an anesthetic.”

Dot came from a family of 10 kids all with the initials D.A.B.

“They called us the Dabs,” she said with a laugh.

After graduation,

Bernard spent 18 months driving a bus three times a day from Montegut to Houma and back.

“I would run 45-man crews to Texaco everyday and pick them up, too,” he said.

In 1959 he got a job with the Terrebonne Parish Waterworks.

He and Dot were married Dot in 1960.

“We had six kids in 10 years” Dot said. “The first one cost $67.”

Devotion to the church did not waver. Duties as an altar boy made way for responsibilities as an usher at Sacred Heart.

Bernard made sure the family went on a vacation every year, “even if it was just to Grand Isle”

“One time, we went to the Cowboy Hall of Fame in Oklahoma. Because we were the 1 millionth visitor, they took our picture,” he said.

Asked if he had any regrets or things he would have done differently, Bernard is quick to answer. “They said it would never work, me and Dot, but it’s been 55 years and it just keeps getting better.”

In 1997, after 38 years of service, Bernard retired from the Terrebonne Parish Waterworks as the plant superintendent in Gray. Still, devotion to the church remained strong.

“I was an altar boy for 25 years,” Bernard said. “And I’m an usher today. Even when I had to travel to conferences for my job, I never missed a mass.”

His other activities include work with the Lions Club, for which he has served as president four times.

He and Dot share an entire wall of awards for their service to the community.

Friendship with Father Roch – though sometimes challenged by distance and varied responsibilities – also never wavered.

Father Roch performed Bernard and Dot’s re-affirmation of their wedding vows on their 50th anniversary.

The two men have words of advice for others based on their life experiences. Asked what they specifically would say to young people, the two were eager to share their thoughts.

“Get out there and work. Experience is the best education,” Bernard advised. “Failure is OK if you learn from your mistakes.”

Father Roch’s advice was less secular.

“Accept yourself for who you are, for how God made you,” he said. “Turn to God for the courage, strength and wisdom to become the person He wants you to be. Be loyal to your parents and obey authority, for you are not just a single individual but a member of the family of God.”

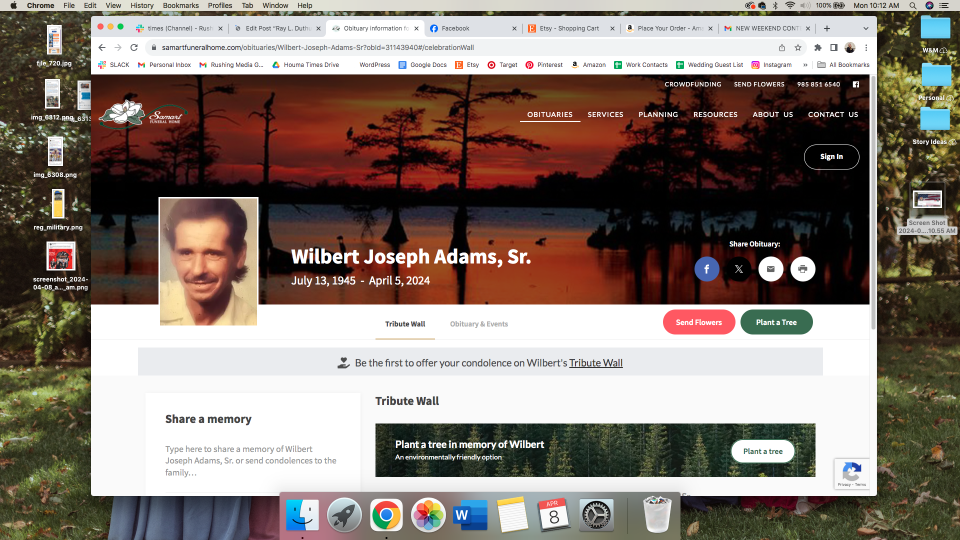

The Rev. Roch Naquin and Bernard Dupre of Bourg, who were altar boys together in childhood, look over photographs at Bernard’s home. The two men have been friends, dating back to the 1930s.

The Rev. Roch Naquin as a child, growing up on Isle de Jean Charles, and his younger sister, Bridget.