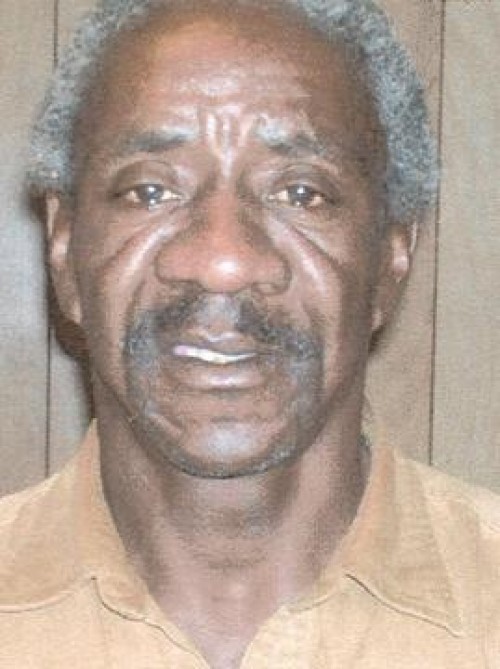

Alfred Stewart

May 25, 2007Yvonne Knudsen- Smith

June 1, 2007Conducting swamp tours for tourists seems like such an obvious moneymaking idea, it’s puzzling that the commercial swamp tour industry in Louisiana didn’t fully take hold until the 1980s, when the tourism boom in Cajun country began to take flight.

Bill Munson, who has operated Munson’s Swamp Tours in Schriever since 1981, said he doesn’t know why the industry began as late as it did, but he credits “Alligator” Annie Miller with being the impetus behind swamp tourism in Louisiana.

(Miller, a well-known local naturalist and snake hunter, operated Annie Miller’s Swamp Tour until 2001, when she retired at age 86. She died in 2004.)

“I have a lot of history with Annie Miller,” Munson said, with a trace of nostalgia in his gruff voice.

Unfortunately, Miller’s legacy has run into rough waters since hurricanes Katrina and Rita struck Louisiana’s coast in 2005.

“I haven’t had anybody in three days,” Munson said on a Thursday morning in mid-May, seated on the porch of the aged wooden structure next to the Ringo Cocke (pronounced “cook”) Canal that serves as the swamp tour’s base of operations. Munson leases the privately-owned canal for his tours. “There’s no hunting, fishing, or trespassing of any kind,” he said. “There’s an abundance of wildlife. You get extremely close to it.”

His assistant, Albert Pellegrin, was getting ready to take Munson’s “party barge” pontoon boat out into the Chacahoula Swamp along the canal to feed the wildlife, since the fauna around the canal hadn’t seen the pontoon boat in several days. The swamp tour also runs along a 125-year-old branch of the Ringo Cocke Canal that was formerly used to haul cypress, according to Pellegrin.

As the pontoon boat with Pellegrin at the helm slowly motored its way up the canal, he threw chicken fat stored in a white bucket to a heron along the bank, which gulped the glistening gobs down quickly.

Pellegrin used to feed the animals on the tour marshmallows and donuts, but “the wildlife seem to prefer the chicken fat,” he said.

It wasn’t much longer before Pellegrin presented the swamp tour’s piËce de rÈsistance. He loaded three chunks of the pinkish-white fat onto a hook at the end of a pole, which he held over the side of the boat, and began whooping out into the swamp.

A juvenile alligator swam at a medium pace toward the side of the boat, briefly circled underneath the inviting cluster of fat, then lunged upward at the pole with a great splash.

Being a juvenile, the alligator seemingly lacked expertise. It overshot the skewered chunks of food, and clamped its jaws on the end of the pole, where it hung for several seconds.

Eventually, the alligator loosened its jaws, fell quickly back into the dark water, and made a second-this time accurate-strike at the overhanging chicken fat, before swimming away contentedly with its lunch.

“The alligators know the sound of the boat,” Pellegrin said. “If I came in with another boat, they wouldn’t come.”

The pontoon boat cruised past nesting boxes set out for tree-loving wood ducks. Pellegrin tossed out pieces of bread to attract raccoons, but only a few squirrels emerged to take up the offer.

“There’s not as many raccoons since Katrina,” he said.

Pellegrin was more successful at feeding a great blue heron along the canal bank, which seemed to eat half a bucket of chicken fat. The heron stood more or less motionless staring at the boat, while slabs of fat dripped from both sides of its long, pointed beak.

For the swamp tour finale’, Pellegrin threw some fat and pieces of bread to a group of black buzzards and a juvenile alligator along the canal bank. The small reptile had to dart in and out from the spread of food to avoid the aggressive birds, but the alligator managed to gobble down a fair share of the bonanza.

Although the buzzards aren’t the most attractive birds, Pellegrin said, “They keep the highways clean.”

As the boat approached its berth on the Ringo Cocke Canal near Bull Run Road, Pellegrin remarked on the decrease in the number of foreign customers taking Munson’s tour since Katrina and Rita.

He said, “Our overseas business is killing us.”

Pellegrin, who said he grew up living in a swamp, mentioned the threat to the Houma area from Louisiana’s receding coastline. He also talked about one recent occasion when he conducted a tour for a former German prisoner of war who had been held at a camp during World War II where the Houma-Terrebonne Airport is now located.

Though Munson’s Swamp Tours has enjoyed more active times in its more than quarter-century history, one thing seemed to point to a better future. Munson keeps an old aquarium on the grounds that hold a special content: two inches-long baby alligators swimming and frolicking in the humid noonday sun.