Plaisance enjoying another WNBA run

July 14, 2015

Sidebar: Post-war politics setting the stage

July 15, 2015As the nation moves toward new dialogue on matters of race and history, largely set in motion by the June 19 murder of nine congregants at Charleston’s Emanuel A.M.E. Church, some local community leaders say the time has come for an accounting of history much closer to home, a conversation that has never occurred about a past many people would just as soon forget.

An unsigned letter in a local newspaper after the 1887 event that has come to be known as the Thibodaux Massacre marks clear a desire for silence.

“Better for all concerned that this page be torn out of our history, rather than try to explain,” it reads.

The dead – when found – were quickly buried, the record shows. There were no coroner’s inquests and no other known official investigation. But historians agree that as many as 30 and potentially many more black sugar plantation workers and labor organizers were hunted and killed, with many more wounded.

The trouble arose from a strike on sugar plantations in Terrebonne and Lafourche, mostly suppressed by state militia over the course of nearly a month. After most of the troops were withdrawn, rumors – as well as shots fired at sugarhouses and civilian pickets enforcing martial law – stirred fear. White riders patrolled black sections of Thibodaux; in some cases shots were fired into homes and businesses. Many black families are believed to have left town never to return.

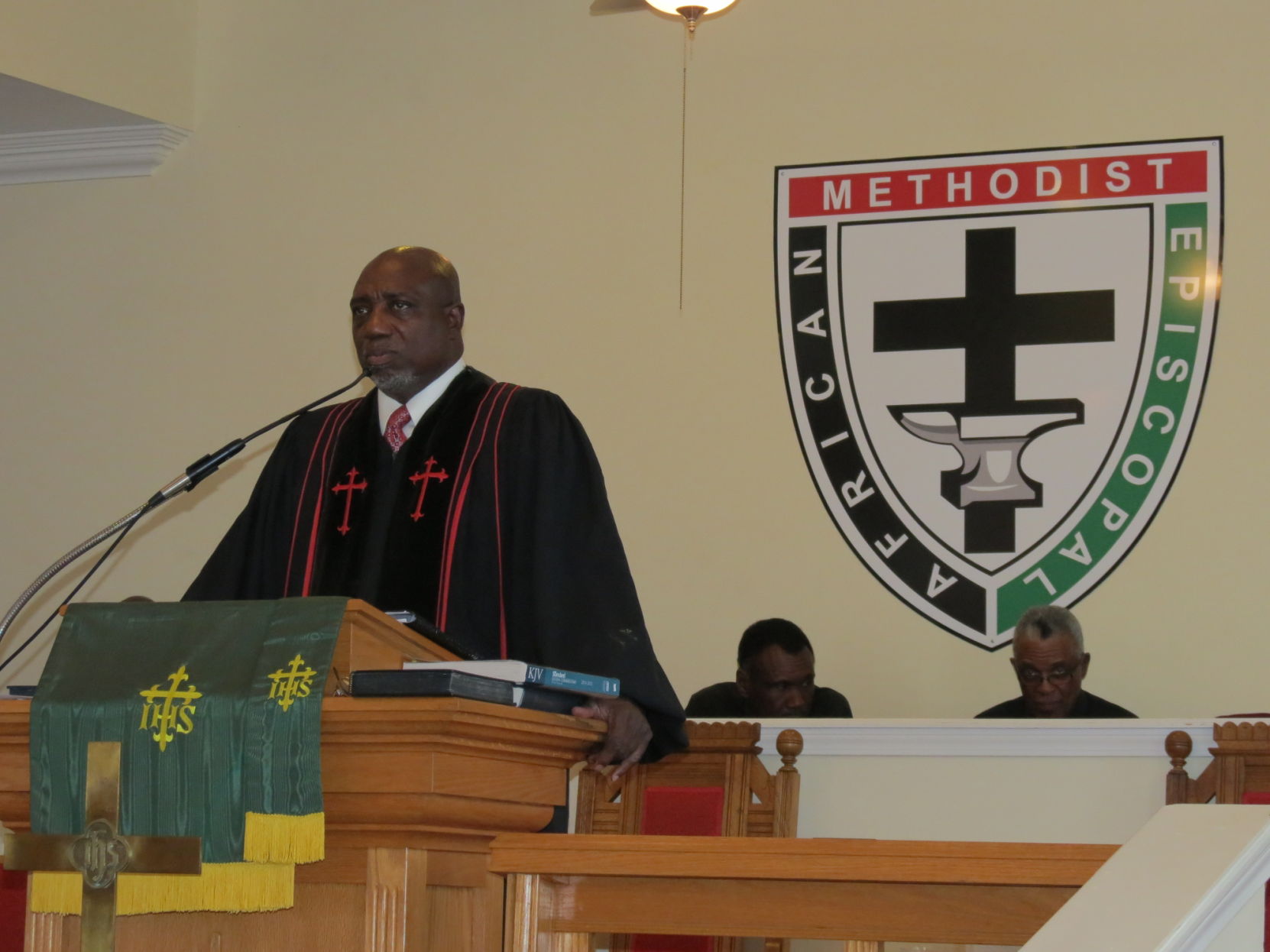

The Rev. Nelson Taylor, pastor of Allen Chapel A.M.E. Church in Thibodaux, was fascinated and disturbed by the topic when he arrived here 10 years ago from Baton Rouge.Taylor, who is also a civil rights attorney, published a synopsis of the history in his church bulletin.

Taylor says the massacre set the stage for a culture of white dominance and black acquiescence that continues to the present day.

“It resonates in a very cataclysmic way in that it was an act of suppression and terror, economic, political and social,” Taylor said. “That one event had to have shaken this community, contributing to a spirit of despair and hopelessness that I think you still see. Nobody confronts anything here. We need to discuss how it really was and how we got to where we are today. The story of what happened in Thibodaux is intolerable and we only know bits and pieces of it. It is so horrible historically that I think people don’t want to remember, both white and black.”

LEGISLATIVE RESOLUTION

Shocked upon recently learning of Thibodaux’s hidden history, state Sen. Troy Brown, D-Napoleonville, said he plans to learn more, and that if what remains of the historical record indicates the need, he will consider sponsoring a legislative resolution officially encouraging a search for answers.

“I would suspect this played a large part in how it affected families, generations of families that are connected in Terrebonne and Lafourche,” Brown said.

Other states have commissioned academic panels to investigate and report instances of racial violence from the past. Among them is North Carolina, which created a commission in the year 2000 to explore – and provide an official report – concerning the Wilmington Race Riot of 1898.

The official death toll in that incident was estimated at 25 black people, though the final report says the true number remains unknown.

Despite the involvement of state militia and a state district court judge in the events of 1887, Louisiana has never officially addressed the events in Thibodaux.

Negotiations between local planters and their labor force were not uncommon by the eighth decade of the 19th Century, as planters adjusted – grudgingly – to the reality of having to pay workers in a post-war, post-slavery economy.

SOUTHDOWN STRIKE

An 1874 strike at Southdown Plantation in Houma, encouraged by black Terrebonne police jurors W.H. Keys and Alfred Kennedy, who were later accused of accompanying 50 men intent on discouraging strike breakers, added to tensions there. It was resolved peacefully but not without an official show of force.

Disputes and disagreements over pay continued on local plantations through the next decade. By 1886, professional organizers were pleading their case to cane workers, who found the union message appealing.

The Knights of Labor, a Philadelphia-based union organization, had set up shop in Schriever, organizing railroad men. The bi-racial organization’s leaders spread through Terrebonne, Lafourche and St. Mary, preaching the gospel of collective bargaining on the plantations. Keys and Kennedy, some accounts say, were among the organizers in Houma.

The effects were evident in January, when a group of workers halted their labors in Lafourche, on Richard Foret’s Mary Plantation. Leaders were jailed, charged with unlawful disturbance and riotous assembly.

Historian Sylvia Frey, in her book “From Slavery to Emancipation in the Modern World,” wrote that a resident of Mary Plantation, Lewis Anderson, disputed the suggestion that organizers were forcing the issue of striking for wages better than 60 cents per day on workers.

“They didn’t make any threats, they didn’t have time to make any threats, because the others were willing to stop (work),” Frey quotes Anderson as having said in court records. Frey concludes that the Knights of Labor were not involved with the immediately aborted Mary Plantation strike.

PLANTERS REFUSE

By October, the hand of the Knights was visible in Terrebonne and Lafourche.

Demands communicated to the growers through the Louisiana Sugar Planters Association were refused.

The Knights had sought three specific concessions: an increase in wages from the prevailing $13 per month, elimination of scrip, or company store tokens and coupons, for pay, and that payment be made every two weeks.

The planters refused to negotiate and on Nov. 1 the Knights of Labor called a strike. “The Negroes are stubborn and generally disposed to stand their ground,” is what the New Orleans Times-Picayune reported.

That publication and others said 10,000 workers – about 1,000 of them white – were refusing to work throughout the region, vowing to remain in plantation housing.

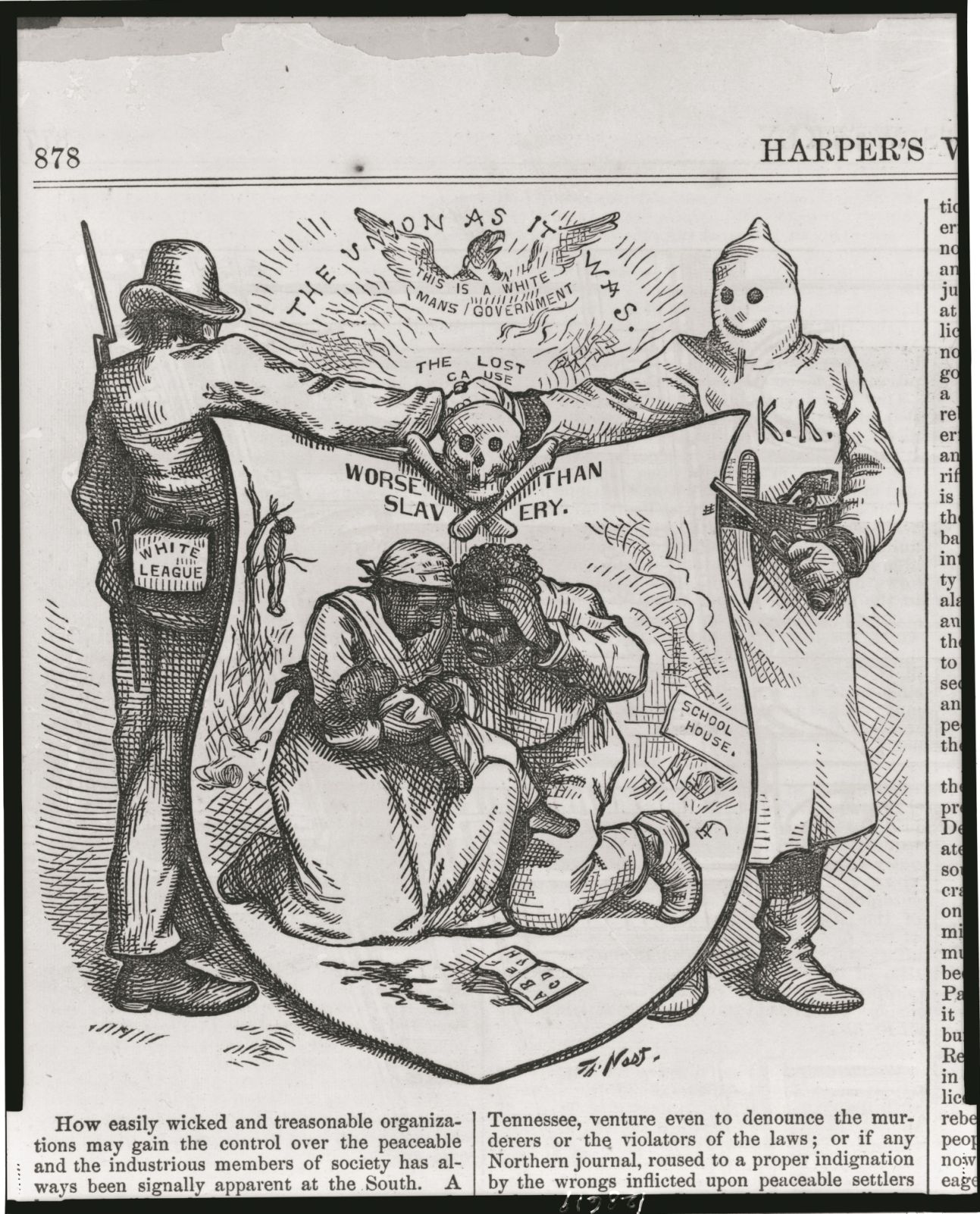

Lafourche Parish District Judge Taylor Beattie, a Republican whom historians maintain was once a member of the notorious White League, was by many accounts “one of the most respected white men in town.” The ex-Confederate officer handled many of the official communications that related to the strike.

Gov. Samuel Douglas McEnery dispatched troops to the region, and they arrived Nov. 2 by rail at Schriever.

Local historian Paul Kleibert obtained records of the Louisiana militia’s reports from the field on what occurred after their arrival at Schriever and made them available for this story.

According to Brig. Gen. William Pierce’s reports, a Gatling gun was prominently placed in front of the courthouse. The Gatling was a hand-cranked weapon capable of continuously firing no less than six brass cartridge bursts at a time, fed through a hopper.

The courthouse served as headquarters for Judge Beattie, who along with other planters met with Pierce to advise him of the situation and discuss strategy.

Pierce told Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard in a dispatch “the Negroes … were in many cases impudent and offensive … I noticed at Schriever a large body of Negroes lounging around the depot and in Thibodaux the streets were full of them.”

Fed and lodged by planters, the troops went to work quelling the strike and protecting replacement workers brought by the planters.

Reports came to Pierce of continued refusal by workers to leave plantations and of non-striking workers or replacements being fired upon, allegedly by strikers or their sympathizers.

“I strongly urged heroic and vigorous action,” wrote Pierce, who dispatched troops to Tigerville, now called Gibson, and to Lockport. Thibodaux had become a quasi-refugee center for evicted strikers. Some gathered in Houma as well. In Thibodaux there were reports that thousands of “idle Negroes” steadily gathered.

Troops enforced evictions signed by judges in Terrebonne and Lafourche, in most cases without resistance.

MORE SOUTHDOWN TROUBLES

At Lockport, where Foret had been shot and wounded, the troops drilled in view of strikers, bayonets fixed, at the quickstep. There, as in other smaller communities, the strikers slowly commenced to work again.

Troops were busy Nov. 5 in Terrebonne Parish, where H.C. Minor had asked for help after hearing that unionists planned to march on Southdown to drive off scabs.

In Thibodaux reports filtered in of shots fired at sugarhouses and incendiary talk by laborers.

On Nov. 17, Judge Beattie and a group of planters traveled to a rooming house where labor leaders were quartered, demanding that violence or threats of violence cease.

Later writings of labor organizers maintain that their fellows were not engaged in violent action or words and that Beattie had stormed out before hearing their protests. They later expressed those sentiments in a meeting with the mayor.

Rumors of plans by blacks to burn the town flew through Thibodaux, bolstering fear from previous claims that black women had threatened to kill white children and women with their cane knives. Military companies were dismissed and returned to their home camps; on Nov. 20, Pierce left Thibodaux for New Orleans on orders, told by superiors his work in the bayou country was done.

Judge Beattie declared martial law in Thibodaux, where the strike had not ended. Plantations owners were panicked, fearing their cane would be lost to a coming freeze. Local discussion, correspondence indicates, began casting the situation less in terms of a labor dispute and more as a burgeoning race war.

OFFICIAL ACCOUNT

Entrances and exits to the town were ordered closed off by Beattie. According to numerous accounts mentioned in the histories, black strikers felt threatened and trapped.

The night of Nov. 20, “strangers” were seen arriving at Frost’s restaurant and hotel. A correspondent writing for the New Orleans Pelican, a weekly black publication, surmised them to be non-uniformed strikebreakers associated with a state militia unit from Shreveport.

Although that account cannot be verified, Pierce’s reports and other sources show that a unit from Shreveport had been dispatched and was expected. Tensions built through Nov. 21, and as many as 300 white men, organized into a “Peace and Order Committee” by Beattie, became visible.

On the morning of Wednesday, Nov. 23, two volunteer lookouts enforcing Beattie’s lockdown, Henry Gorman and Joseph Molaison, were shot and wounded by snipers on St. Charles Street.

The New Orleans Pelican’s accounts say the vigilantes committed the deed themselves. The townsmen blamed strikers. Other accounts say there was no way to know.

A joint account later attributed to Beattie, Lt. Gov. Clay Knoblock and other officials states that “a fearful state of excitement arose and the armed guards of the town rushed to the scene of action.”

“They were again fired upon from ambush, and then returned the fire by a general fusilade, which was kept up until the rioters were dispersed,” the missive states. “Some six rioters are known to have been killed and as many wounded. None of the guards of the town were injured except those above mentioned. Our people are determined to preserve the peace and all good citizens are in perfect accord.”

“NO DEFENSE”

That official dispatch – even in publications favoring the local government and the planters – was challenged by other newspaper accounts, which surfaced in days to come. The historical record, fattened by letters between planter family members, also paints a picture far bloodier than the matter-of-fact report.

The Monroe Bulletin, a pro-planter publication, reported that 25 strikers had been killed and others wounded.

The Southwestern Christian Advocate told of “Negroes being imprisoned in town … White guards in the town of Thibodaux attacked the Negroes on the streets or in their houses, and murdered men, women and children to the number, it is believed, of not less than thirty-five. There was no defense, and the Negroes fled to the swamp like frightened sheep. So the strike was suppressed, we judge, (with) no white man being killed.”

The New Orleans Pelican’s stories diverged farther.

“Six killed and five wounded is what the daily papers here say,” a Pelican correspondent wrote. “But from an eye witness to the whole transaction we learn that no less than thirty-five Negroes were killed outright. Lame men and blind women shot; children and hoary-headed grandsires ruthlessly swept down. The Negroes offered no resistance; they could not, as the killing was unexpected. Those of them not killed took to the woods, a majority of them finding refuge in this city.”

If violence against whites had gelled into anything more than rumor, there is no record of arrests or prosecutions for such, nor injuries, death or property destruction by blacks beyond the scattered sniper reports.

MORE VIOLENCE REPORTED

Mary Pugh, mistress of Dixie Plantation, wrote in a letter that her son Allen had ventured to town and reported that the gunfire sounded like war.

Yale historian Jeffrey Gould, summarizing Pugh’s letters and other correspondence from that time, says in his treatise that vigilantes stormed a brick rooming house on St. Charles where strikers and their families were staying.

Pugh wrote of seeing Andrew Price, a local planter, dragging a black man from a house along with an armed mob, and provided other vivid recollections, including one from just outside her home’s side door, where she observed blacks corralled by vigilantes.

“I thought they were taking them to jail,” Pugh wrote. “Instead they walked one over to the lumber yard where they told him to run for his life (and) gave the order to fire. All raised their rifles and shot him dead. This is the worst sight I saw and I tell you we have had a horrible three days and well excelled anything I have seen during the war.”

An account in the Lafourche Star describes “negroes jumping over fences and making for the swamps at double quick time. We’ll bet five cents that our people never before saw so large a black-burying as they have seen this week.”

Other accounts told of fleeing blacks drowning in Bayou Lafourche while escaping gunmen.

Letters tell of vigilantes pursuing their prey into woods and describe numerous wounded strikers.

Mary Pugh herself estimated the number of dead at 50.

Pugh’s letters – which include language her modern lateral descendants condemn – make clear that she, like members of other planter families, were not sympathetic to the cause of the strikers.

After expressing her horror at the violence Pugh wrote, once quiet returned, “I know it had to be, else we would have all been murdered before a great while. I think this will settle the question of who will rule, the n—– or the white man for the next fifty years. But it has been well done. I hope all trouble is ended. The n—–s are as humble as pie today. Very different from last week.”

EPILOGUE

After the smoke of vigilante guns cleared Lafourche and Terrebonne returned to business as usual. Andrew Price, seen dragging a man from his house with a mob, became a congressman the next year. A now unused school in Schriever is named after him, and a public gymnasium in Thibodaux.

Republican Taylor Beattie, the judge who enabled the massacre, ran against the Democratic Price in 1896 and lost, though the election was officially contested. Analyses of the strong support for Beattie suggests that sugar plantation workers were bullied into voting for him.

The lot of predominantly black workers in the sugar parishes did not improve and Jim Crow laws prevailed for many decades to come.

While some black leaders maintain the massacre story needs to be told – perhaps on a properly placed historical marker or, as noted by Sen. Brown, through a legislative resolution and possible historical investigation – there are also words of caution.

“I believe in history, that history should be told,” said Lafourche Parish School Board member Richmond Boyd. “But I don’t want to see something done that will cause division.”

Thibodaux City Council member Constance Johnson, who is black, said she first heard about the massacre from her grandparents and has done further study.

“I had just found out some years ago that near the American Legion hall is where some of the bodies are buried,” Johnson said. “Our past is a reflection of our present and our future and I do believe that some of the events that occurred in the past have relevance today.”

Thibodaux NAACP President Burnell Tolbert said that while the story of the massacre is distasteful, good comes of examining history as a way of moving forward to the future.

“It’s a very ugly history,” Tolbert said. “But sometimes we have to look at history, no matter how ugly it may be.”

FOOTNOTE:

This story was written after careful review of newspaper clippings, books and magazine articles as well as interviews of historians and other people over a period of nearly 10 years.

In some cases, where primary sources were indicated in footnotes, we endeavored to locate those primary sources whenever possible. In order to proceed proper context we have relied on extensive works that are the product of great scholarship. They are listed here.

Eric Foner: A Short History of Reconstruction (Harper & Row, NY) William Ivy Hair: Bourbonism and Agrarian Protest (LSU Press, Baton Rouge) John C. Rodrigue: Reconstruction in the Cane Fields (LSU Press, Baton Rouge) Rebecca Jay Scott: Degrees of Freedom (Harvard University Press, Cambridge) Sylvia Frey and Betty Wood: From Slavery Emancipation in the Modern World (Taylor & Francis, NY, London) Jeffrey Gould: The Strike of 1887: Louisiana Sugar War (Southern Exposure, Nov-Dec 1984 based on his Yale University dissertation.) Stephen Kleinert, Thibodaux, La. (Internet blog and collection of Louisiana militia records) Nicholls State University Special Collections, LSU Special Collections, UNC Special Collections. Some sources were used to verify the veracity or likelihood of material contained in others.

We are grateful to all of these people and others we may have neglected for their scholarship and dedication.

— JOHN DeSANTIS