Ramona Tipton

February 2, 2012

Stuart John Stein

February 6, 2012Flowers still line the halls of Troy and Angie Danos’ Larose home.

Though no longer fully bloomed, they explain the scope of today’s meeting n the impact made by a special young man.

Hand-written cards and personalized gifts lie scattered all across the various nooks and crannies of the family’s humble residence as Troy politely leads a tour through the home.

“Excuse the clutter,” he says. “We’re still trying to get everything organized.

“It’s been a busy few weeks.”

That’s an understatement.

The conversation moves from the family’s kitchen table to a bedroom on the left side of a halfway within the house.

Now letting his wife take over touring duties, Troy watches as Angie twists a doorknob and pushes open a door to unveil where the young man spent most of his nights n a neat room clad with swimming trophies, a TV, a bed and a giant exotic fish hauled in during a family fishing trip.

“This was Dylan’s room,” Angie says.

Out of the bedroom and back in the Danos family’s living room, Dylan’s face looks on in several photographs on the wall n his charming smile, his youthful exuberance, his overall love for life.

That love didn’t burn near as long as the South Lafourche community would have hoped as Dylan passed away on Jan. 5 at the age of 17 due to complications from a lifetime battling cystic fibrosis.

But while the body may no longer have life, the young man’s parents say Dylan’s spirit will live forever.

The Danos family shared their son’s journey this week, recapping just how many lives this South Lafourche teenager reached in his short time on earth.

“I am the man I am today because of my son,” Troy Danos says with a smile, looking at a photograph of his son. “He’s truly an inspiration. To do the things he did, to live the life he lived in just 17 years, it’s just amazing. It really is. My son is my hero.”

“We had no idea,” Angie Danos adds when asked about her son’s impact. “We just find out more and more every day. People tell us how he touched them and inspired them.

“We knew he was special. We knew he touched us and we knew he touched other people, but we had no idea the extent of his inspiration.”

“We could tell pretty early that there was something significantly wrong with our son,” Troy Danos says, remembering the earliest days of his son’s life.

Dylan Danos was born premature on Nov. 19, 1994.

From the earliest days of his life, he had problems with his health, specifically with his lungs.

“He just couldn’t breathe properly,” the father remembers. “He would, quite frankly, turn blue.”

At 3 months old, doctors misdiagnosed the infant and ordered him to go through a surgery for an ailment he didn’t have.

“It nearly killed him,” Troy Danos says.

He eventually recovered and was properly diagnosed with cystic fibrosis, an ailment that attacks one’s lungs.

But the surgeries and the time in the hospital were just getting started.

Troy and Angie Danos say there is “no way” to give an exact number of surgeries their son has endured, saying it’d be too many to remember off the top of their heads.

They added their home away from home throughout their son’s childhood was a hospital room.

“It was very hard,” Angie remembers. “We had our good days and our bad days. We had our up moments and our down moments, but it was very hard.”

Although Dylan needed special care, one thing he never wanted was special attention.

Both Troy and Angie sit back and laugh, remembering Dylan’s mentality. He never wanted to be treated differently than anyone else.

He never wanted to be known as “the sick kid.”

“Cystic fibrosis was not going to define who Dylan was,” Troy explains. “He never wanted to be remembered or known in that way.”

“Dylan did not want to be different in any way, shape nor form,” Angie remembers. “He wanted to be just like everybody else. He wanted to try everything like everybody else did.

“Dylan always just had this magnetism. Everyone was always so attracted to him, even when he was a small kid. We’d go on vacation and Dylan’s just 3 or 4 years old and people and animals and things we just didn’t even know were just attracted to Dylan. He had a magnetism about him. Everyone always wanted to be around him.”

The way the parents attribute Dylan’s positivity is simple n faith, family and friends.

“He trusted that ultimately he was going to wind up in a better place,” Troy Danos says. “And that played a big part in his life.”

“He had us, he had his grandparents, his cousins and his friends, everything like that,” Angie Danos adds. “He had a lot of people around him giving him support. People that Dylan looked up to. That’s a big plus. Not everyone has that.”

Through his own self motivation and positivity, Dylan progressed through school and grew up a normal teenager n as normal as anyone dealing with cystic fibrosis could be.

He made it all the way to high school, enrolling at South Lafourche High School.

During that time, the medical outlook started to change for the teenager, leading him to take drastic action.

“Dylan looked the doctor in the eye and told him, ‘I hear what you’re saying, but now you listen to me, I’m going to swim in the district meet and I’m going to the homecoming dance,’” Troy Danos remembers with a laugh, envisioning his son in a Houston hospital. “The doctor agreed just to keep his spirits up, but they didn’t give him a chance to do any of those things.

“But he did it.”

Dylan loved the outdoors n specifically being on the water and fishing.

He also loved to swim, a sport he participated in since early childhood.

The teenager progressed in his love and became a member of the Tarpons’ swim team.

“To be a part of a team,” Angie says nodding her head in approval. “That just meant the world to Dylan. And they were always accommodating, they always did whatever they could to make Dylan feel like he was part of the team. They never pressured him to do anything when he was sick or pushed him when he was in the hospital or anything.

“We cannot say enough how grateful we are to them for being so accommodating to our son. I know being with them meant the world to Dylan.”

Danos swam for the Tarpons as a freshman and had success, establishing himself as one of the team’s top young talents.

But as a sophomore, he just couldn’t do it anymore.

The condition had progressed and he just couldn’t compete n nor live normally n without being exhausted for hours.

“It took a huge toll on him,” the mother says.

With few options for a full recovery, Dylan opted to try a “Hail Mary pass”, a double lung bypass surgery.

For the teenager, it was one last crack at being normal.

For his parents, who were studying the odds of the procedure, understanding the risks involved, it was a gut-wrenching process.

“We left it up to Dylan,” Troy says. “It was his decision. And the doctors were brutally, brutally honest to our son about what could happen and what the dangers were. Almost too brutally honest, especially when you’re a parent hearing these things. But Dylan understood what they were telling him. And this was what he wanted to do.

“He was at a point in his life where simply walking up a flight of stairs was impossible. Where simply getting up, being mobile and getting out of bed was a challenge. This gave him a second chance.”

Another motivation for the teen n the district meet and homecoming.

Danos missed his sophomore year of swimming because of the condition’s rapidly increasing impact on his lungs.

“He didn’t want to miss out again,” Troy proclaims. “He was going to swim in that meet. He was going to go to homecoming.”

He did, but not without a fight n much like everything else the boy accomplished in his life.

“I thought we were going to fall apart,” Angie says remembering the August day when her son was rolled from a hospital bed into an operating room. “And I see Dylan and he’s giving us thumbs up and he’s still so cheerful.

“How can you not be a little more at peace when you see that?”

“It’s an amazing sense of pride as a father when you see your son act so brave,” Troy remembers.

Danos underwent the surgery, an extensive, several-hours-long procedure.

Doctors deemed the procedure a success, but the parents still proceeded with caution, expecting to see a shell of their son lying in a bed.

Dylan admitted following the procedure he was in pain.

But he didn’t overtly show it, expressing pure, genuine love for his newfound life even while still in the initial recovery phase.

“The first sentence we shared after his operation, he told me, ‘Dad, I finally know what it’s like to breathe again,’” Troy remembers.

With new lungs and a new lease on life, Dylan started to live.

As soon as he was cleared, he began an extensive exercise regimen to help condition his lungs.

The teenager worked so hard on his own that he didn’t need the hospital-supplied workout program offered to him.

“It would have been repetitive,” the father says. “The things they told him to do, he was already doing on his own.”

Dylan wanted to get back to swim in that meet.

He was not going to take no for an answer.

“The doctors were amazed at the progress he made and how fast he got to the point where he was able to come home,” Troy says. “But that was Dylan. He was determined. He told them from the get-go, this is what he wanted to do.”

With his body healed, the doctors were still weary of freeing Dylan to return home. The teenager was taking dozens of pills a day and the his physicians worried whether he would take the right pills at the right time in his own care.

“They gave him his medicines and by the end of that week, he had everything memorized,” Angie recalls. “He wasn’t going to let something like that keep him away.”

“Once the doctors saw that, they had no choice but to let him come home.”

Dylan returned to South Lafourche and swam in the district meet. He also attended homecoming. For a several-months-long stretch, the teenager truly was normal and did everything his friends did.

“Dylan cherishes those times,” Angie says

“He did an awful lot of living in that short time, I can assure you,” Troy adds.

But shortly after his son swam in the district meet, Troy said Dylan was hospitalized with an infection n something that wasn’t supposed to be a mere blip on the teenager’s radar.

It ended up being much more than that.

It signified the final days of his life.

“You learn a lot about living when you watch someone slowly slip away,” Troy says, thinking back to watching his son lie in his hospital bed at Houston’s Texas Children’s Hospital.

Dylan was diagnosed with the infection early this winter.

At the time of the diagnosis, Troy said Dylan was concerned with one thing n a family fishing trip he was now sure to miss.

“That really disappointed him,” the father remembers.

What was supposed to be a fairly routine trip to the hospital for the teen ended up being much more as the viral infection continued to progress, making Dylan seriously ill.

Doctors all across Houston’s Texas Children’s Hospital huddled, traded notes n anything to keep Dylan alive.

The parents share stories about the nurses in the hospital working extra hours to care for Dylan.

“They did everything humanly possible,” Troy remembers, still visibly wowed by the efforts. “The doctors, the nurses, everyone, no one wanted to see Dylan go.”

Dylan passed away on Jan. 5 due to what the parents believe are complications from the viral infection the teenager’s immune system couldn’t beat.

A full autopsy will release more details in future months.

“You fight for 17 years and you wake up on Jan. 6 and it’s like, ‘What next?’” Troy says. “It’s a very, very lonely and empty feeling.”

After Dylan’s passing, the family received hundreds of cards, dozens of flowers and countless messages from people all across the country.

The entire south Lafourche community rallied to show their support for the 17-year-life of one of their own.

“It’s unbelievable,” Troy explains.

“You know, we take it for granted sometimes,” Angie adds. “But we truly are blessed to live here.”

Through faith and that community support, the Danos family is now working to encourage organ donation, saying Dylan’s transplant gave him a couple of months of life that he would have never gotten without it.

The father said he plans to partner in a book to encourage positivity in parents and patients of those dealing with cystic fibrosis, adding that he and his wife know “for certain” Dylan wouldn’t regret getting a transplant.

“He wouldn’t do anything different,” the mother says.

The father shared an excerpt Danos wrote on Aug. 27, 2011, which is going to be featured in the book. In it, the teenager expresses in summary his life’s journey.

“Well, all I could tell everyone is that my life hasn’t been the easiest, but I have had some really great, bad and some never forgettable memories,” the excerpt reads. “I can honestly tell you that my life has been nothing short of great.

“There were times when all I wanted to do was stay in bed and not get out or do anything, because of some of the things I have been through. Other times, you couldn’t get me to rest for five minutes, much less [lie] down in a bed and sleep,” he wrote.

“Through all of the bad and good times, all of the bad doctor visits, the surgeries and everything else that happened in my life, I wouldn’t want to change it for anything else.”

Dylan Danos lived like a hero.

Even in death, his message lives on.

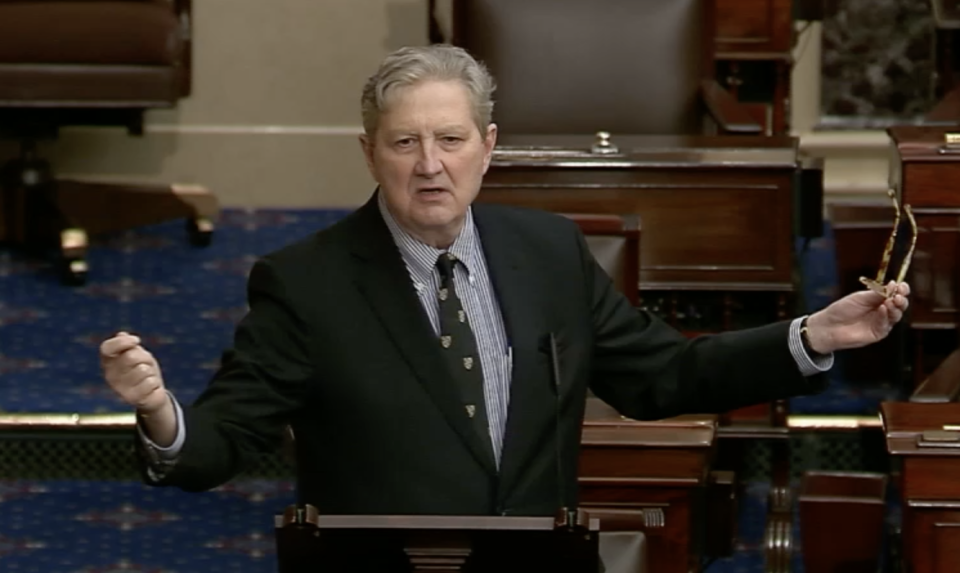

Larose parents Angie and Troy Danos pose with a swimming trophy inside their late son Dylan Danos’ room. The parents shared Dylan’s story this week, a tale of bravery and positivity in the face of a 17-year fight with cystic fibrosis. CASEY GISCLAIR