Thursday, June 9

June 9, 2011

Curtis Joseph Leblanc Sr.

June 13, 2011At about the time seafood industry leaders thought they would be able to make a return following last year’s negative market results from the BP Deepwater Horizon explosion and oil release in the Gulf of Mexico, oyster and crab producers are facing a new threat as fresh water from the flooded Mississippi and Atchafalaya rivers invade saltwater reaches to threaten their summer harvests.

According to the Marine Stewardship Council, Louisiana produces 50 million pounds of blue crab every year. Half of that total harvest is caught in the Terrebonne Basin and in Lake Pontchartrain. At the same time, the state produces 100,000 pounds of soft shell crabs in those areas.

During the past week, rumors circulated in crabbing circles that a lack of bait due to flooding and the intrusion of fresh water into areas of high salinity were prompting a dismal season.

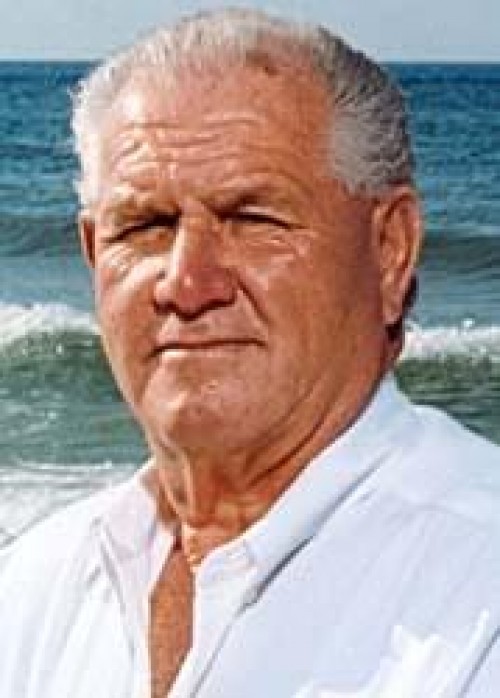

“It’s not a big deal,” said Raceland’s Fishing Jim Seafood owner Roger Manning, who insists that fears and speculation are more damaging than reality.

“There are about three facets to the bait [issue],” Manning said. “One of them started three or four years ago. A lot of farmers are getting out of catfish farming and going back to planting crops. That’s because the price of grain and crops has been up and the profitability of raising catfish has been marginal.”

Manning noted changing practices in raising catfish, the heads of which have traditionally been used as crab bait. According to an LSU Agricultural Center report, the total area for Louisiana catfish farming in 2002 was at 12,100 acres. By 2010 that number had dropped to 2,000 acres. Manning blames cheap foreign imports for hurting domestic catfish farmers.

“The biggest problem this year was the river crest,” Manning said. “The river flooded where the [catfish] farms are at in Arkansas and north Mississippi and even the northeastern corner of Louisiana. Some [catfish farmers] had to harvest their fish early and some waited for the river to come up and their fish swam off.”

Manning said that a shortage in bunker bait, also known as moss bunker or crank bait, resulted because of an early crawfish crop where it is also used. A good harvest of crabs in the northeast put higher demand on the bait, and cool water temperatures during the spring reduced the number of available bait. The most recent bait of concern Manning said was striped bass, which was also in short supply as the season opened June 1. “[But] bait should be coming available,” he said.

Manning blamed an over reliance on local bait supplies without alternative planning for current concerns. “Every now and then, you get a 100-year flood and things change,” he said.

“I had 13 pallets brought down last week,” Manning said. “I’m not a bait dealer. I don’t handle bait. But I made sure my fishermen had bait. Now, if they don’t get bait, I’m not going to complain.”

Along with a hit to crabs, the oyster industry in Louisiana took a 50 percent loss following the BP spill and according to forecasters, is expected to take another 50 percent hit on what remains of a potential harvest due to the release of fresh water from the Morganza Spillway and the Bonnet Carre Spillway.

“We’re getting reports of mortalities in central Louisiana, meaning below Marsh Island in Vermillion and Iberia parishes, and western Terrebonne,” Motivatit Seafood CEO Mike Voisin said. “We are also expecting it in lower Plaquemines Parish because the [Mississippi River] is overflowing levees in the very end of the river and into those areas that produce quite a few oysters.”

The Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries lists the oyster industry as being a $30 million contributor to the state economy. Terrebonne Parish generally contributes 25 percent of the state’s oyster production.

Oysters, along with crab, shrimp and other segments of the seafood industry had been damaged during the past year by federal regulations and public perception regarding the safety of Gulf seafood following the BP spill. Now they are faced with a threat flowing from inland areas.

“Oysters thrive in 5 to 15 parts per 1,000 salinity in the Gulf,” Voisin said. “During this time of the year, they are going through a reproductive cycle and they are weak at that time. So if you over freshen them with water that is generally warmer than what they are used to, then they will die.”

When freshwater diversions were opened at this time last year in an effort to stop oil from flowing into marshlands, it killed a large part of the available oysters and even resulted in some producers going out of business.

“We are expecting losses where we didn’t lose oysters last year,” Voisin said. “We will lose into the hundreds of millions of dollars worth of oysters. Because when you lose an oyster, you don’t lose just that year’s crop because there are three-year classes on the bottom. They all die and it takes three to four years for them all to come back.”

Voisin described himself as an optimist and said he looks at the two year flushing of the oyster business as an opportunity to clean the offshore environmental system and predicted that if all the conditions cooperate, a record oyster harvest could be anticipated in 2014.

“What it means [in the meantime] is we are going to have less to sell outside the area,” Voisin said. “The market outside the Gulf states is a little dry right now. If we had to have a flood where we get less product, maybe this is the time.”

Voisin and Manning separately confirmed that public perception plays a significant role in the success of their businesses. They are trusting that even with the setbacks that face them, in time the market as well as the environment will turn in their favor.

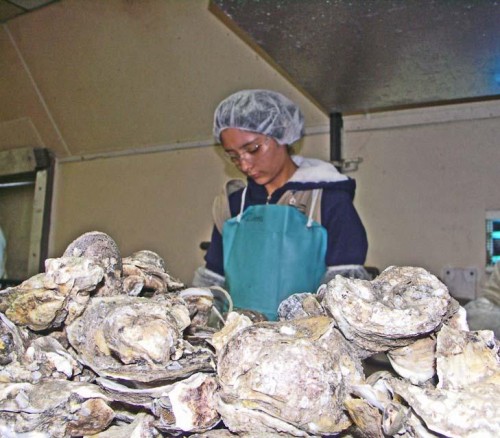

Maria Flores works through a pile of oysters on the production line at Motavatit Seafood. Waters from the Mississippi River and the Atchafalaya River are expected to cause another loss to the annual harvest. FILE PHOTO