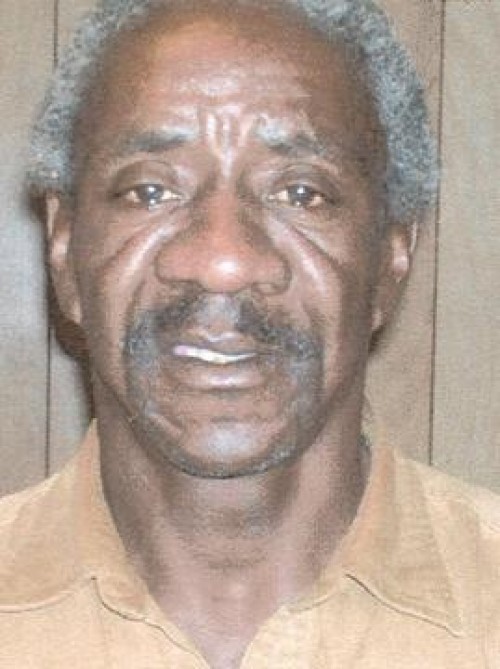

Alfred Stewart

May 25, 2007Yvonne Knudsen- Smith

June 1, 2007Jody Meche says he was frog hunting with his two sons in the Atchafalaya Basin one night about two years ago when he heard a rifle shot and saw the bullet strike the water nearby.

“I told my boys to get down in the bottom of the boat,” Meche said, recounting how he called his wife on his cell phone to tell her he had been shot at, then steered toward the source of the gunfire.

What he found, he said, was an angry hunting club member ordering him to get off a private hunting lease on Lake Rycade.

“My dad grew up right there. I grew up fishing and trapping and frogging with him there all my life,” Meche said.

Lake Rycade, an area off the channel of the Atchafalaya River, has become a focal point in a controversy over waterway access in the basin.

Similar disputes are playing out across the state, from the bayous of Lafourche Parish to the backwaters of the Mississippi River in northern Louisiana.

Gunfire is rare, but the controversies seem no less a battle between landowners and those who, in the extreme, argue that they have a right to go wherever their boats can take them.

The best sport fishing on rivers is along the banks and in the backwaters n just the type of spot along the Mississippi where a group of fishermen claim they were casting lines when East Carroll Parish sheriff’s deputies cited them for trespassing.

The angry anglers responded with a federal lawsuit, contending they have a right to be anywhere that the river at high water can take them, even if the water flows over land considered private when dry.

“They say you can’t fish between the ordinary low and high water of the river, which is where everybody fishes,” said Monroe attorney Paul Hurd, who represents the East Carroll fishermen in the 2001 lawsuit.

The case has attracted the attention of the Louisiana Wildlife Federation and fishing clubs from eight states, including the Yankee Bassers of Maine, who joined to file legal arguments in the lawsuit in support of the East Carroll group.

A federal magistrate gave hope to the fishermen, opining in his recommendation to the higher-up district judge that the public has a right to fish on rivers up to the high-water mark, regardless of who owns the land beneath the flowing water. But U.S. District Judge Robert James thought otherwise.

In a decision now on appeal, James ruled that the public’s right to use a river up to the high-water mark is limited to activities related to navigation _ anchoring a boat in need of repair or traveling from one area to another.

Fishing does not qualify, he said.

Concern over the East Carroll decision stretches from northern Louisiana down to coastal Lafourche Parish, where commercial and recreational fishermen have been fighting battles over access for years.

“That was a good case for us, until the judge ruled it wrong,” said Bobby Bryan, a fishing guide in Leeville who works the coastal marshes. “How those people can own the water I don’t know.”

Louisiana Wildlife Federation Executive Director Randy Lanctot said that if the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals affirms the East Carroll decision, fishermen could find themselves pushed out of waterways they have enjoyed for decades.

Depending on the application of the ruling, it could affect areas that stretch from a few feet to a few miles outside of the main river channel.

Lanctot said the state wildlife federation is considering a push for legislation to designate in state and federal law that fishing is allowed on navigable waterways up to the high-water mark.

“That would be a bill we would be opposed to,” said Newman Trowbridge Jr., a Lafayette attorney who is general counsel for the Louisiana Landowners Association, a group that also has been keeping a close eye on the East Carroll case.

Trowbridge said any bill to allow fishing on rivers up to the high-water mark would be an attempt to “legislatively overrule the several cases that have ruled otherwise.”

New Orleans attorney Constance Willems, who represents the landowner in the East Carroll case, said the restrictions on public use between the low and high water are a matter of settled law, even if a magistrate judge thought otherwise.

“I think people want to use this as a test case to open up additional access they don’t have,” Willems said. “They want to go wherever the Mississippi goes. You are talking about potentially large areas of land.”

That’s exactly what a group of crawfishermen in the Atchafalaya Basin have in mind.

“If it goes under water, anybody has a right to go there,” said Mike Bienvenu, a Catahoula crawfisherman and president of the Louisiana Crawfish Producers Association-West.

The group was formed in the 1980s to address low crawfish prices but has morphed into an public-access advocacy group. The group’s members have had limited success in their legal battles.

But in the case of Meche n LCPA-West’s vice president n the push for access to Lake Rycade has yielded a few rare victories.

A state judge in December 2005 declined to side with a hunting club seeking to bar nonmembers from a lake that Meche argues is public.

A federal lawsuit filed by Meche against the hunting club member who he alleges shot at him in February 2005 is pending. The club member denies the allegation.

Other states have passed laws that specifically say whether fishing is allowed up to the high-water mark on a river. But some public access advocates are wary of pushing for such a law in Louisiana, fearing the legislation might turn in favor of landowners.

“When you start opening policies dealing with public access, that door can get shut in your face,” said Chris Horton, conservation director for the national recreational fishermen group BASS, which is monitoring the East Carroll case.