Locals excited about Saturday’s All-Star game

March 26, 2014

Pair charged in fiery death of children

March 26, 2014Held in 1927, the trial was one of the most sensational events to ever hit St. Mary Parish, transforming the sleepy town of Franklin from sovereign parish seat to carnival site.

But in later years the case – and the two executions that resulted – became cloaked in ever-more layers of silence, morphing into a dirty little secret concerning a scandalous love triangle not discussed in polite company.

The case arose from the shooting death of James LeBoeuf, the Morgan City power plant’s superintendent, during a mysterious midnight boating trip on Lake Palourde.

At the center of it all was his wife, Ada LeBoeuf, branded a murderess but in the eyes of descendants convicted and hanged rather for adultery, the first woman ever executed in Louisiana. Her alleged lover, a prominent physician named Tom Dreher was hanged as well. But the man believed to have actually fired the shots, James Beadle, escaped the gallows and, after a dozen years of imprisonment, lived out his life a free man.

The story has been the subject of a book and some articles, but details remained hushed; in some cases family members entered adulthood unaware of their ancestors’ roles in a swing era melodrama smacking of Peyton Place.

Just this year, a former university librarian who extensively researched the case has had difficulty finding a venue to present her findings, told that too many prominent people might find it offensive.

The librarian, Fran Middleton, is scheduled to speak today at the Bayou Vista Public Library, focusing on how Beadle, a hunter, fisherman, trapper and confidante of the doctor, used the skills of his trades to up the legal ante and evade the full force of the law. She had hoped to speak before members of some groups in Morgan City, but was told prominent people whose lineage relates to the case would be angered. In Middleton’s opinion the modern-day reluctance has its roots in early 20th century sensibilities that became evident after Ada’s fate was sealed.

“I think the result of the shame was the idea of hanging a white woman in 1927, the behavior of the people in the courtroom and their failure to realize the gravity of the situation,” she said. “Life was dull, it was colorless, and this was excitement. The press kept up frenzy during the trial. I don’t believe anyone thought Ada was going to get executed. The shame that resulted from this execution, I think, is people looked back and thought, ‘What have we done, what have we become?’”

The jury itself asked for clemency after convicting Ada of murder, but it was denied flat-out by Louisiana’s newly elected governor, Huey P. Long.

“You will be hanged by the neck until you are dead, dead, dead, dead,” was the pronouncement by the trial judge, James Simon, and it stood.

Wearing a simple pink housedress, faded from laundering, Ada swung from a gallows built inside the St. Mary Parish jail on Feb. 1, 1929. Dreher was hanged from the same gallows about 20 minutes later.

“Oh mother, mother. My God, this is murder itself. Oh, God. Isn’t this a terrible thing? Oh God, who can do this thing? It is worse than murder itself. Oh, oh, that rope is too tight … yes it is,” are the last words Ada was reported to have spoken before the trap was sprung, according to accounts related by Middleton.

Events leading up to the fateful conclusion began in 1925, when Ada, a mother of four children, sought the professional services of Dreher due to headaches.

Medical treatment transformed, by most available accounts, into something more.

According to reports at the time of the trial, Ada signaled the married doctor that her husband was away by hanging a slip on the laundry line.

Tongues wagged but the gossip did not reach her husband for two years.

When it did, according to available printed accounts, James LeBoeuf sought out the doctor and gave him a direct death threat.

According to the theory presented by the prosecution, it was Ada who told her lover that action must be taken against her husband to save his own life.

A ride in Lake Palourde with her husband in a skiff was the recipe alleged to be a cover story. The ride occurred on July 1, 1927.

Middleton related newspaper and blog accounts of what was believed to have happened next.

Dr. Dreher had also set out on a skiff, with his handyman. Dreher had a pistol and Beadle had a shotgun, which Middleton notes would not have been unusual at that time.

Relatives have maintained the meeting would indeed have been arranged, a rendezvous in a place where prying eyes and ears wouldn’t get a chance to see or hear, for the air to be cleared.

What was clear after the Dreher and LeBeouf skiffs met up was that Ada’s husband, hit twice in the chest with shotgun blasts, would never be seen alive again.

The body, weighted down with iron, was dumped into the lake.

For nearly a week, Ada told neighbors that her husband was away on business; then the body was discovered by three froggers.

At first it could not be identified, so complete was the desecration done by marine life and the elements of summer.

Ada gave several versions of the story upon questioning and ended up getting arrested by her brother-in-law, Morgan City Police Chief Louis Blakeman.

District Attorney Emile Vuillemot presented his case of conspiracy, enhanced by a last-minute statement from Beadle.

It was the cunning and sharp sense honed through years of out-smarting wildlife, Middleton maintains, that put Beadle in a position to have the upper hand, to the point where his own attorney ended up cross-examining Ada and the doctor, in addition to the questioning they underwent from Vuillemot. It is a legal exercise that would never occur in a courtroom today.

That is what Middleton prepared as a chief topic for her talk this week.

“It is my belief that James Beadle shot James LeBoeuf,” is Middleton’s conclusion. “Ada never held a weapon. Although she had said that Dreher fired a pistol, he was blind in one eye and the shot was made at night. Beadle was a hunter and was experienced at shooting in many different conditions.”

In the years following the executions, the case was not discussed with the next generation resulting from the ill-fated LeBoeuf union.

“Our family never thought she did the murder or lured James out there to be murdered,” said Lynette Davis, Ada’s great-granddaughter. “Was there an affair? We think so. We think Ada was maybe threatened afterward, that someone said, ‘Look, don’t tell anyone what we did.’ We are fairly certain she knew Dr. Dreher planned it but we don’t think Ada was involved in the conspiracy.”

Davis did not learn about the case until she was in high school.

“It was a real touchy situation,” she said. “My cousins grew up not knowing anything about the story.”

A version of the story was in Louisiana history books at the time, although Ada’s kin never made the connection.

That was until a classmate with whom Davis had a disagreement said, “At least my grandmother didn’t murder my grandfather.”

Davis mentioned it to her mother – Ada’s granddaughter – who gave her a book relating to the events.

“She told me never to mention it to my grandfather, Ernest, who was Ada’s eldest boy,” Davis said.

Ernest, his brothers Joseph and Herman, along with their sister Liberty, were present for every day of their mother’s trial.

“Ernest took it the hardest,” Davis said, noting that after the hanging he “had a nervous breakdown and ran away.”

Davis and a handful of other relatives have continued piecing together what they might know about the case and its aftermath.

They are still learning.

Last week, they discovered the grave of Beadle in the Morgan City cemetery, buried not far from the separate graves of Ada and James LeBoeuf.

Dreher’s family has long since moved out of state, though some relatives may be left. There are still remnants of Beadle’s family remaining in Morgan City. But none of them are talking. A few years ago, Davis broached the subject with her grandfather, emboldened because she knew he had seen promotions for a television series that would feature a story on it.

“He said she was a good mother,” Davis recalled. “And that it tore up our family.”

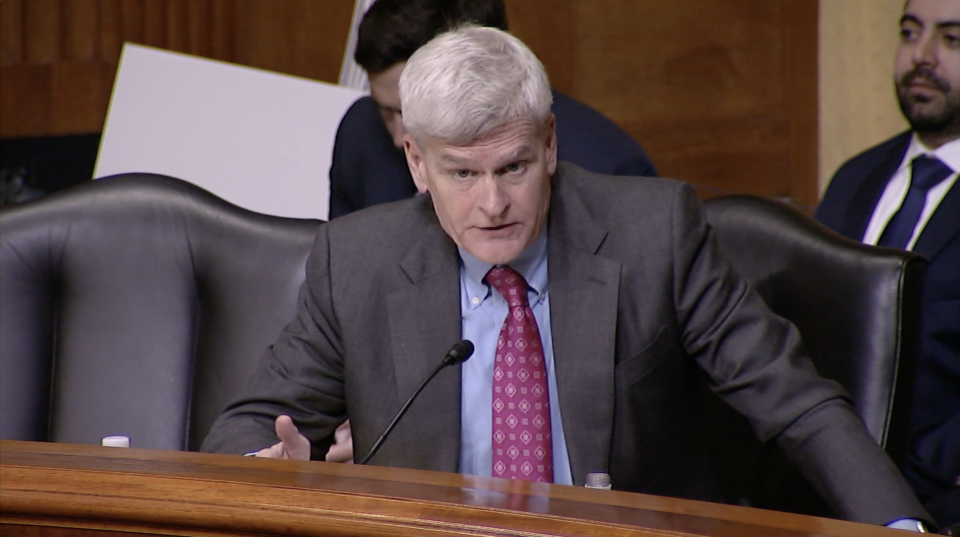

Former librarian Fran Middleton peruses materials she has collected during two years of investigating the case of Ada LeBoeuf, executed in connection with the 1927 murder of her husband, Frank LeBoeuf. Middleton is giving a talk on the case Wednesday at the Bayou Vista library. At top are Dr. Tom Dreher, Ada LeBoeuf and James Beadle.