Voltaire J. Bergeron Sr.

July 15, 2014Law, launch litigation block grocer

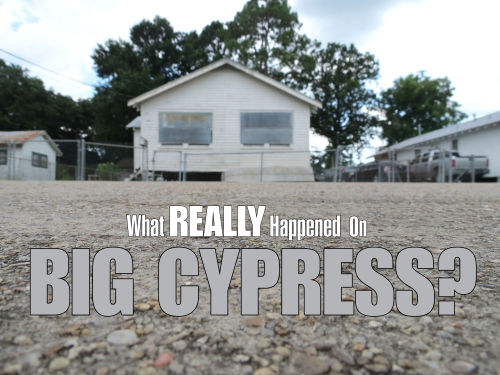

July 16, 2014When Ray Carlos called police at a little after 3 a.m. on July 6, he said the man lying dead on the other side of his Big Cypress Street home’s chain-link fence had lunged at him, posing a threat so grave that he was forced to shoot.

And then a different story got told.

Nikki Lynne Frickey, a 32-year-old medical technician who lives diagonally across the street, told officers she saw her highly intoxicated boyfriend, 29-year-old James C. Rube II, walking toward the Carlos residence apologizing to Carlos for waking him.

“He was talking as he is going. As he gets closer, he says, ‘I am sorry, I apologize,’” Frickey said in a later interview. “Carlos said, ‘I am not going to warn you twice.’ James is still walking, he says, ‘I’m sorry, again. Then Carlos says ‘punk,’ then BLAM, then I don’t see James anymore.”

“I’m sorry, then ‘punk,’ then blam,” she says multiple times, while pointing to the small, broken ornamental window from which she says she witnessed Rube’s last moments of life.

WAR WIDOW

July 6 marks the second time Frickey has lost someone she loves to violence. The first was the husband she relocated to Houma with from their native state of Michigan.

In 2005, her husband, Sgt. Armand Frickey, of the Louisiana National Guard’s 2nd Battalion, 156th Infantry Regiment Charlie Company – Houma’s “Black Sheep” brigade, was killed with six other soldiers when a roadside bomb in Iraq blew up his Bradley fighting vehicle.

Then, as now, she sought to avoid the spotlight, protesting that she doesn’t want stories about this latest personal tragedy to focus on her.

“This isn’t about me, this is about James,” she insists.

But Frickey’s status in connection with the case is unique, and her role impossible to ignore.

Frickey is the only known witness to the shooting, precipitated by the allegedly drunken Rube banging on the door she refused to open, following a late night, text-and-telephone quarrel.

Their tempestuous, star-crossed relationship of eight years, five of them spent with Rube imprisoned and Frickey awaiting his release, which eventually led to Rube’s walk toward Carlos and his gun.

The suggestion that Carlos may have saved Frickey’s life from a boyfriend bent on violence has already been voiced in open court, during a hearing last week that saw the shooter’s bond reduced from $1 million to $10,000 cash. The hearing gave the first indication that Rube’s violent, intrusive and bizarre behavior at Frickey’s doorstep could come into play when grand jurors are charged with determining if criminal charges are warranted, and it will certainly be aired if there is ever a trial.

But investigators warn that the two incidents – Rube’s prior actions and those later taken by Carlos, allegedly in self-defense, are two entirely different matters and should not be mingled.

Mutual friends say Frickey was – and is – in denial, that her boyfriend’s propensity for violence against her presented a threat to her.

The war widow rejects that idea with unflinching force.

“They made me sound like a victim,” she said of reports relating to the court proceeding. “I am not a victim. James was not going to hurt me. I could handle James just fine.”

BRICKHOUSE MEETING

For more than a year after her hero husband’s death, Frickey says, she remained withdrawn.

“He would call me every day from Iraq,” she said. “It was very hard. I took it very hard. I went to work, but I pulled away.”

And then one night, she relented, going out with a friend to the Brickhouse on Houma’s Main Street.

It was there that she met James Rube, a Texas native who was the son of a factory worker. He had just turned 21 and Frickey was 24-years-old.

Described by Frickey as well-spoken and charming, Rube had spent most of his life in Iowa, where he took criminal justice classes at a community college. He had only recently relocated to south Louisiana, to join his mother, Darlene, and stepfather, Tony Verret.

Verret secured him a job on the oilfield vessel Minnie Falgout, and Rube appeared to enjoy the work.

From their first date, Rube made an indelible impression on the widow.

“He saved my life,” she said. “He got me to live again. I had been inside myself. I didn’t have a lot of friends here. I was thinking this is nice, this is really nice.”

Rube gave her a ring he picked out with his mother that Christmas.

“He said this is my promise to you, today, tomorrow and yesterday,” Frickey recalled. “He knew how to make me happy.”

Work on the Minnie Falgout did not last.

DOWNWARD TURN

While continuing to see Frickey, Rube worked at several Houma land-based jobs, including a stint at the Outback steakhouse and the Rain Forest car wash.

Rube split his time between his family’s home in Gray and Frickey’s Houma apartment. Frickey set him up with his own apartment in Thibodaux, which she eventually moved into.

“When we moved to Thibodaux, things started to change with James,” Frickey said. “Thibodaux was a change in plan, he made different friends.”

She continued to dote on him, however; acknowledging that she would take him shopping for clothes she knew would look good on him, seeing to it as much as she could that he wanted for nothing. They ate out frequently and shared their good times with some of his friends.

Drug use became evident. The relationship between Frickey and Rube had devolved into one that was more open – on his end – and there was occasional violence.

“Our relationship did get physical,” Frickey admits, but says that if Rube struck her she didn’t call police. The two of them, she said, managed to handle the rough spots themselves.

The violence, the making-up and breaking-up that became the dramatic pattern for the relationship was considered by the two of them to be the norm.

BUSTED

On April 7, 2008, the couple was involved in a car wreck in Houma. Police found drugs in the vehicle, a 2006 Honda Accord. Both Frickey and Rube were arrested.

Both were booked for possession with intent to distribute Xanax, a Schedule IV drug used to treat anxiety. Rube was also charged with possession of marijuana. That was because of previously-smoked marijuana cigarette stubs – or roaches – found in an ashtray, which he told authorities were his.

Frickey said she had a valid prescription for the Xanax, which she has taken ever since her husband’s death, leading to eventual dismissal of charges against her.

Rube’s case was continued.

Two months later, an incident occurred that had a major impact on both of their lives.

According to Frickey’s recollection, Rube was at a cookout with family members at the Tanglewood apartment complex on Stadium Drive in Houma. Frickey was not there.

A group of teens on bicycles passed the group and allegedly uttered what were described as “rude” words toward some of the women at the gathering.

Rube and a friend got into an SUV, which belonged to the friend’s girlfriend, and searched the area for the youths, whom they found nearby at Main and St. Charles streets.

ANGOLA BOUND

According to a police account, Rube and his friend were stopped at a light when the teens, aged 14 and 15, approached on their bikes. Rube fired a single shot at the ground, which ricocheted, grazing the chest of the 15-year-old.

Subsequent to investigation, police arrested Rube at an east Houma apartment, booking him on charges of assault by drive-by shooting and aggravated battery.

A deal was made combining that incident with the pending drug charge and Rube was placed in the custody of the Louisiana Department of Corrections, sentenced to five years.

While still at the Terrebonne jail in Ashland, nearly a year later, Rube was charged with second-degree battery in connection with an incident there, which friends said was itself a case of self-defense.

As he moved through the corrections system, from jail to the state penitentiary to work-release assignments, Rube stayed in close touch with Frickey and family members, vowing to come out of prison a better person, with a life on a better track.

In November 2013, he was released on parole, with a plan for reintegration. He moved into the home of his parents in Gray.

FUEL TO HIS FIRE

Rube kept in touch with his parole officer and within a week was working at the Edison Chouest Offshore-owned LaShip, earning the respect and friendship of co-workers and supervisors.

“They loved him there,” said Darlene Verret, relating how her son’s co-workers nicknamed him “Deuce” – because his name is James II – and how he thought nothing of doing small favors for people on the job.

He also reunited with Frickey. Some of her friends disapproved, citing the history of what they saw as abuse but what she saw as the price paid for a life with the man she loved.

Members of Rube’s family disapproved, describing her as “the fuel to his fire.”

As Rube settled in to life with his family, ties began unraveling. Determined that her son would not stray into bad company and bad habits, Darlene Verret imposed rules that Rube found oppressive.

Some – like attending services at First Baptist Church of Houma – Rube found easy to follow. Others, not as much. Among those was a prohibition on alcohol use.

“At first his mom and dad were all hesitant about us being back together,” Frickey said. “The rules they made included him staying in the house. But he wanted to drive, he wanted to be free, to be outside, he wanted to be in the sun.”

BUNKHOUSE RULES

As he and his mother struggled, there were consequences. The truck Rube drove was taken away and, eventually, he made arrangements to move. Darlene set him up with a room at Houma’s Sugar Bowl Motel.

Frickey made clear that she had a new attitude, and wanted Rube to adopt one as well. The relationship would no longer have a “physical” aspect; there would be no hitting.

“We were going to have a family and be together,” she said. “We both knew we had been through hell and back but we were going to succeed. James and I had an understanding. He was going to respect me.”

Weekends saw Rube and Frickey spending quiet time together at the house she rents on Big Cypress Street.

There were no problems evident to neighbors other than occasional loud music from their vehicle – an SUV owned by Frickey – or the vehicles of visiting friends.

Frickey, disapproving of the Sugar Bowl choice made by Darlene, moved Rube into the Bunkhouse, the men’s residence on the east side of the Houma twin span. She didn’t know, she said, that the Bunkhouse had rules nearly as strict as those at Darlene’s home, nor that the accommodations – meant to be temporary – were so spartan.

Rube avoided conflict with the Bunkhouse rules when he wanted to drink, doing so on the bank of Bayou Terrebonne or at Frickey’s house.

She maintains that five years in prison changed the nature of her boyfriend’s drinking.

“He couldn’t hold his liquor anymore,” she said, noting how he became easily intoxicated. Problems ensued.

HOUSE TRASHING

In early June, Frickey had gone out with a girlfriend and Rube called her, asking if he could retrieve a bag he left at her house.

“I had already showed him how to get in when I wasn’t there,” she said.

A drunken, sulking Rube damaged items in the house, including Frickey’s television. Frickey’s friends were distressed, particularly an oilfield worker who had once been a mutual friend but no longer socialized with Rube.

“We dealt with it,” Frickey said. “We dealt with it in our own way.”

When the July 4th weekend rolled around tensions between Rube and Frickey had eased. Rube had spent time with his mother, which she described as “absolutely wonderful.”

There was a cookout at the Verret’s house in Gray, after which Frickey drove Rube to Houma, dropping him at the Bunkhouse. He later texted her and she picked him up; they spent the night at her home.

Frickey described the next day as pleasant.

“It was a really good day,” she said. “He took my truck to run errands. Then later he went to the east side with me and I paid my payday loan; later I took him to the Bunkhouse.”

FLURRY OF TEXTS

At 8:30 pm Frickey suggested in a text that they go watch the fireworks scheduled for 9 p.m. But Rube did not respond until nearly 10 p.m., telling Frickey he had no money to do anything but that he was on his way to a store.

At 10:40 p.m., Frickey indicated that she was crossing the twin span and picking up Rube. He bought some vodka and beer at Shop Rite on Grand Caillou Road and returned with Frickey to her house.

Rube downloaded some music to his phone, utilizing Frickey’s Wi-fi, as she prepared for a quiet night of romance. But before Frickey opened her beer, Rube said he wanted to go back to the Bunkhouse. She drove him back but not before telling him that she was certain he would be asking to come back in an hour. She was partially correct.

He didn’t ask, he just rode back to Fricke’s house on his bike, arriving there shortly after midnight highly intoxicated. There were some words between Rube and neighbors from across the street, said Frickey, who had experienced enough of him for the night.

“I had already seen that he was drunk, I was turned off, I wasn’t going to let him back in,” she said. “Those were the rules.”

Rube texted her that he was riding his bike on the twin span, then texted that he was going to go to his mother’s house.

He called his mother and said he wanted to come over; he had not eaten, he was hungry and he didn’t want to be alone. Nobody from there came and got him, however.

“I wish I had come for him,” said Darlene, who now copes with the pain of second-guessing tough-love decisions.

Rube continued meandering around Houma, ending up on the grounds of Terrebonne General Medical Center, where he fell off the bike.

“I crashed,” he told Frickey in a text at 1:37 a.m. “Please come get me.”

“Are you serious,” Frickey texted. “I just turned out my lights … saw a cop drive by.”

Hospital security officer Percy Mosely found Rube, apparently asleep on the grounds and sent him on his way. There was no confrontation. Mosely did not call city police.

But Frickey, concerned about Rube’s welfare, did call – without giving her name – and said there was a man who had a little too much to drink driving a bicycle around in the area.

FINAL MESSAGE

In court last week, authorities confirmed that the city police subsequently made contact with Rube – unknown to Frickey – but sent him on his way as well, exercising their discretion and not making an arrest. Such extensions of goodwill, officers say, occur occasionally, especially when a motor vehicle is not involved.

At 2:17 a.m., Frickey texted Rube and asked if he was OK. By the time he responded, he was already back at her house.

“F— you,” he texted.

That message, at 2:43 a.m., was the last Frickey would ever receive from him.

At 2:47 a.m., Frickey called the Houma police, saying there was still a problem regarding a man on a bicycle. A dispatcher said the police had already been there. Frickey said they needed to return.

At 2:50 a.m. twice, and then at 2:51 a.m., Rube called Frickey’s phone but she did not answer.

He was very possibly banging on her door at that point.

At 2:52 a.m., Frickey texted her offshore worker friend – the one who disapproved of their reuniting. His name has not yet appeared in any public record, and he has asked not to be identified, fearing repercussions at his job.

“You busy?” Frickey texted. ”Never mind. I know you said call, so I did.”

Frickey and the friend conversed; he later said he could hear the banging on the door through the phone. Fearing for Frickey’s safety, he left his Raceland home and headed for her house. On the way there, he called 911, struggling to relate the exact location as he didn’t know the street address. During the call, the friend told authorities he was afraid Rube would kill Frickey, that he himself had a gun and was en route.

Frickey, he maintains, underplayed the possibility of harm from Rube. She says that the friend was over-reacting.

“From a long time ago, my belief was that one of them would end up dead at some point,” he said in an interview.

BLOOD ON THE PORCH

Rube broke a small decorative window to the right of Frickey’s front door, cutting himself. The cut on his hand bled all over her porch. She said he told her he was cut and she threw a towel out of a side door, which he retrieved.

“I didn’t see the blood,” she said. “I didn’t believe him. I kept telling him to go home and go to bed.”

It was around 3:15 a.m., according to all available accounts, that Ray Carlos stepped out of his house, 100 feet and across the street from Frickey’s home.

“It’s 3 o’clock in the morning, what’s all that boom-boom-boom,” Frickey said she heard Carlos say. “I heard James say ‘it’s OK, it’s just me, I’m pounding on my girlfriend’s door. I’m sorry, sir.”

At no time is Carlos known to have left his yard, nor made any attempt to come to Frickey’s aid or had reason to do so.

LAST WALK

Frickey said she watched through the pane with the broken glass as Rube advanced toward the street, toward the chain link fence behind which Carlos stood, the view partially blocked by a neighbor’s crape myrtle tree.

She also texted her friend.

“Now he’s arguing with my neighbor,” she texted. “He’s going to start a fight.”

The urgency of the message, she later said, was to get the friend to respond more quickly, to defuse whatever situation was occurring.

At no time, she said, did she see Rube charge at Carlos or act in any way that was threatening.

Carlos, Frickey said, gave another warning.

Rube, she said, had his hands at his sides except when he apologized; when he spoke those words, she said, he was waving them again.

Almost to Carlos’ gate, Rube – according to Frickey – again said, ‘I’m sorry.’”

Carlos fired. Rube went down. Frickey undid a security door-block, which was at floor level and ran outside. She recalls waving her hands in front of her. Carlos, she said, was on the telephone, still at the gate where the bleeding Rube lay dead.

“I went straight for that man’s throat,” Frickey said. “He was talking on the phone and saying, ‘I just shot somebody’ … I said, ‘No you didn’t, no you didn’t. Why?’”

TURNED AWAY

Frickey’s friend arrived and pulled her away from the gate. He confirms that Carlos was on the phone as well. The street was swathed in blue as police cars arrived. Carlos was handcuffed and Frickey told her version of events to an officer and the investigation began.

On Frickey’s door, written in blood from the hand-cut that Rube had suffered, was the word “nothing.”

In court, attorneys opined that it was directed toward Frickey. She maintains it was Rube’s assessment of himself, of what he felt at that moment he was to her and others in his life.

Last week, Frickey donned a black dress and headed to the Samart Funeral Home where services were held for Rube, who had been cremated.

She sat in the back, with four empty rows in front of her.

“I prayed and I talked to James,” she said.

A family member told her that it was best she leave. Frickey complied.

As the investigation continues, police are still examining evidence. The friend’s 911 call is something authorities maintain is proof that Frickey was in danger, despite her protests.

As friends and relatives of Carlos await what they hope will be exoneration, those closest to Rube say they are hoping for a trial. He has made no public statements since his release on bond and is not expected to.

They also want to know why police did not arrest Rube for riding his bicycle while drunk. Most of all, they say it is not possible that Rube meant Carlos any harm.

“He had no right to do this, he had no reason to do this,” Darlene Verret said. “He did not know my son.”

Ray Carlos was released from Terrebonne jail last week after posting $10,000 in bond. Meanwhile, investigators continue to seek answers in the Houma man’s July 6 shooting of James Rube just feet away from his yard. The case could test Louisiana’s “stand your ground” law.