Father Todd: Sensitivity to others’ needs makes a big difference

March 21, 2012

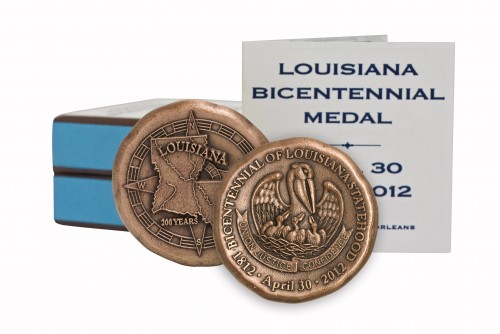

La. Bicentennial coin set on sale

March 21, 2012Celebrity can be a frightening thing at times. For example, Paris Hilton and Kim Kardasian are well-known for being, well, known. And, maybe, just maybe, for being not so smart, at least in the traditional I.Q. kind of way. But others become well known because they are both slick and powerful. And this is the story of such a person.

Joe McCarthy blazed across the American political landscape in the early 1950s. In a span of weeks, he was transformed from a Washington small fry into one of the most visible figures in the nation. In just months, he became one of the most feared men in the United States. McCarthy was the master of the pseudo event; his was the art of accusation without documentation.

The senator’s notoriety began in the pastoral hills of West Virginia when he claimed he had the names of 205 Communists who worked in the State Department (different accounts have put the number at 81 and 57).

Coverage of McCarthy’s charges grew like a snowball rolling downhill, although specifics of what the senator had to say were essentially nonexistent. The reason was simple: McCarthy offered no specifics. As Associated Press correspondent Edward Olsen put it: “The man just talked circles. Everything was by inference, allusion, and never a concrete statement of fact. Most of it didn’t make sense. I tried to get into my lead that he had named names but he didn’t call them anything.”

If what he said was true, even just a little, then there was cause for concern. Just one Communist in the State Department was too many. So the charges were news, and the wire services and many newspapers believed they had an obligation to cover the story.

Here was the dilemma the media faced: Covering news that was not quite news, press conferences that were ambiguous but somehow important, allegations by important people against persons of lesser notoriety, and therefore lesser news value. The press essentially tripped over its own objectivity. Interpretation was often infrequent and after the fact. Truth became an elusive shadow on the wall, and the press became a casualty of McCarthyism.

Where McCarthy was involved, however, knowing something and writing about it was akin to holding water in your hands. Time pressures that the wire services faced sometimes led to stories that, under more normal circumstances, would never have been published. But dealing with the senator was anything but normal. His methods, although appearing simple and straightforward, somehow confused the most astute reporters, leaving more than one in a convoluted state of mind. Here how it went. Early morning: McCarthy calls a press conference to call a press conference at midday at which time he announces a press conference that evening. McCarthy’s “electrifying” morning statements were somewhat less than electric and almost always timed for early deadlines of newspapers in the Eastern-time zone. Clarification would take place at the noon press conference. The strange part was McCarthy rarely looked bad. And he had accomplished his goal of spending another day in the headlines.

And what were the readers to think? Question: Would a United States senator appear before Congress and make false claims? Question: What were the chances of a senator making charges of this magnitude without some sort of substantiation? Question: How could anyone expect the senator to have exact numbers since the Communists certainly would not provide him with a spy directory? Question: How could charges so vast not have a kernel of truth?7

Answer: If the untruth is bold and confusing enough, the Big Lie becomes believable. It is not small or simple or easily understood.

Since he never provided substantive evidence to either the government or the media, and since no Communists were ever uncovered by his investigations, it would seem McCarthy’s news value would have quickly diminished after the Wheeling speech. That did not happen, however, as McCarthy proved he could become a human pseudo event, a person known for his well-knownness.

McCarthy’s charges deserved coverage. But how much, and for how long?

When substantiation for his claims were not forthcoming, newspapers and the wire services had to decide whether or not McCarthy stayed on their agenda. The answer to this was muddy at best. Fear of some sort of infiltration by Communists had been an issue since the first Red Scare in 1919-1920 and had markedly increased since World War II. In 1947 the Hiss/Chambers controversy boiled, and in 1949 the State Department opposed further aide to the Chiang Kai-shek and the Nationalists in China. Republicans strongly opposed this policy as either stupid or traitorous. For the political parties, communism as both a domestic and a foreign affairs issue was real. The time was ripe for someone to make communism less abstract for the public. Enter Joe McCarthy.

What helped McCarthy with both the public and the press were the “specifics” of his charges, even though they were false. Republicans had been criticizing the State Department’s policies for years but in general terms. McCarthy offered numbers, and even though the numbers changed, they were there for the press to print. Once printed, the agenda as it applied to McCarthy was set in motion. For some, the question of whether McCarthy should have remained on the agenda for any length of time is moot.

McCarthy had a knack for publicity perhaps unmatched by any politician of his generation. There was a P. T. Barnum quality about his politics and press maneuverings that, in retrospect, shows he had no plan, which turned out to be the best plan.