William Marmande Sr.

March 19, 2015

Xavier Keion Richard

March 20, 2015As a contentious Terrebonne Parish injection well near homes and businesses moves closer to going online, opponents are gearing up for what could be the final showdown in a three year long battle against it.

The Terrebonne Parish government, which had dropped its own fight against the well, must now decide whether to pick it up again.

Aside from concerns over contamination of drinking water, opponents worry about carcinogenic air pollutants being released so close to a school, church, homes and parks.

Some nearby residents are fearful of health risks posed by the operation of the well, which is located at New Orleans Boulevard just south of North Hollywood Road.

“I really wish they wouldn’t do it,” said Allen Dumond, who owns a home near the well and works offshore… There are contaminants they’re pulling off of the waste oil tanks [that] are more than just gray water going through the system… They’ll be pumping no telling what [into that well.”

Brandon Gawlik, owner of Vanguard Environmental, con-

tends that there is no danger posed to the community by his company’s injection well.

“I’ve got five little kids and a pregnant wife that are at that office every day,” Gawlik said. “So if I was doing something so bad, then why would I have them there?”

Saltwater injection wells exist throughout the state. There are over 20 of them in the Houma area. The difference with this well is that it is a commercial well that will be pumping waste water under northern Houma from oil producers throughout the region in an area that is surrounded by homes, a school, a church, a playground, and businesses.

Parish law would have prevented the well from ever being drilled had not state law, which is more lenient, superseded it.

The Terrebonne Parish Council is set to decide later this month whether to join in court action being undertaken by two environmental groups, seeking to have the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality reexamine a decision the agency made.

The Vanguard well was given an automatic exemption from being required to get an air pollution permit.

We Can Guard Houma and the Louisiana Environmental Action Network are two groups that went to court challenging the process by which the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality granted an air emissions permit exemption to Vanguard Environmental, an oil field waste-water disposal company that has drilled a saltwater injection well on their property.

This is the final round in a fight against Vanguard that has lasted more than three years.

Vanguard Environmental collects brine, or salt water, from onshore oil wells in the region. The brine, a high-chloride water-based solution, is a by-product of oil extraction. The brine contains oil and sometimes heavy metals and radioactive materials.

The brine would be pumped into Vanguard’s injection well leading into a naturally occurring underground sand formation that would absorb it like a sponge.

Oil producers who do not produce enough oil to warrant the investment of drilling their own injection wells turn to disposal companies like his, Gawlik said.

INJECTION OR WISHING WELL?

The Louisiana Department of Natural Resources gave Vanguard a permit to construct the injection well in May 2011. State law requires that a well of this type not be within 500 feet of a house, school, or church, which Vanguard’s location is not. But Terrebonne Parish has a law that bans such wells within a mile of homes and other occupied structures.

The well site is within a mile of St. Gregory Barbarigo Church and school, Glenn F. Pope Memorial Park, Williams Avenue Recreation Center and a neighborhood filled with homes.

The question was whether state law or parish law was right.

In 2012, Vanguard sued Terrebonne Parish over the ordinance and won. Terrebonne Parish appealed to the Louisiana First Circuit Court of Appeal and lost again. In November 2013, the parish took the matter to the Louisiana Supreme Court, which dismissed the case without a decision. The state law, the courts ruled, trumps the parish ordinance.

In total, the litigation cost Terrebonne Parish nearly $115,000, said Parish President Michel Claudet at last week’s council meeting.

Vanguard appeared to have a green light to move forward with the well, but there was one measure the opposition had to work with.

In order to receive an underground injection well permit from the DNR, Vanguard had to either get a permit from the Louisiana DEQ to release air pollutants, or prove they would produce less than certain thresholds of those pollutants per year.

THE AIR PERMIT

Air pollutant permits issued by the state DEQ have a built in exemption for companies that say they will pollute less than a certain amount. The agency does not verify these claims nor does it give the public any notice about companies that will soon be releasing chemicals into the air.

The DEQ considers an air permit to be a “minor permit,” said Wilma Subra, a chemist for LEAN.

“Frequently, when DEQ receives an application and reviews it, they issue the minor permit without even having any public comment or public notice and that’s how the rules are written,” said Subra, who is among people wanting that law to be changed.

An operation like Vanguard’s may produce no more than 5 tons per year of any individual pollutant and no more than 15 tons per year collectively in order to be exempt from getting an air permit, said Brian Johnston, a senior environmental scientist in the air permits division of the DEQ.

“Per the calculations that they provided at DEQ, their facility would be exempt from the need to obtain an air permit,” Johnston said.

Johnston said that the way the state legislature wrote Act 547, the law governing air emissions permitting, makes the exemption “self-implementing,” meaning that there is no classification, certificate, or status issued by the state DEQ so long as the company says the requirements are met.

In 2009, Vanguard Environmental contracted engineering firm T. Baker Smith to calculate their pollutant emissions rates to submit to the DNR. According to the report submitted to the DEQ, T. Baker Smith calculated that Vanguard Environmental’s primary pollutant would be volatile organic compounds. Those are regarded as the potentially harmful vapors released by oil and other petroleum products.

T. Baker Smith also reported that Vanguard Environmental would release a total of 3.4 tons of VOCs into the atmosphere, which is below the threshold and qualified them for an air permit exemption.

That amount, 3.4 tons of VOCs, is based on the facility processing 4,000 gallons of brine per day.

But that is significantly less brine than what Vanguard Environmental said they would process daily on their application for an injection well permit with the state DNR, said Chris Domangue, founder of We Can Guard Houma.

“So there was a major, major, tremendous discrepancy on what they told the two agencies dealing with the volume of waste they were going to be accepting at this facility,” Domangue said.

According to Domangue, Vanguard’s application to the DNR said they would process no more than 28,800 barrels of brine per day, the

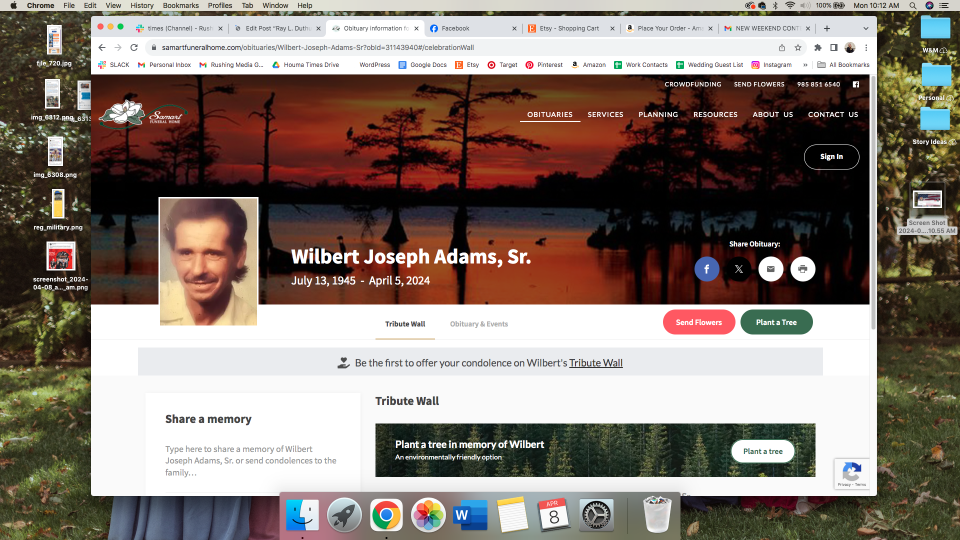

Pictured is Vanguard Environmental’s saltwater injection well site next to their office on New Orleans Boulevard just south of North Hollywood Road. The well has been drilled, but the surface facility has not been built, pending the outcome of litigation brought against them.

A jar filled with the brine that Vanguard collects and will be injecting 4,800 feet below Houma. The brine is actually less toxic than the sand the well will deposit into, which contains more chlorides, or salt, than the waste water does.